Health & Medicine

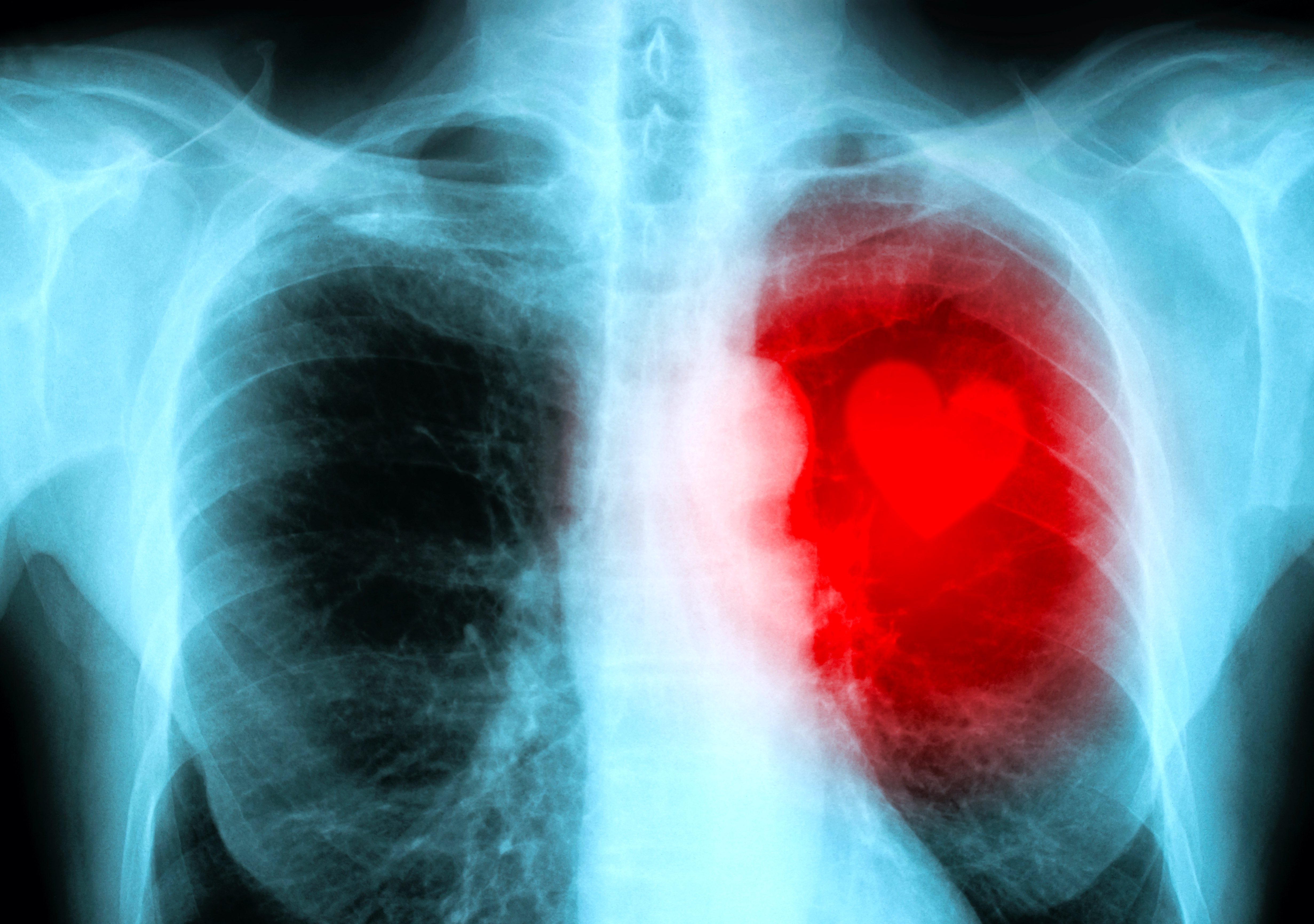

Are declines in cardiovascular disease mortality ending?

For decades, the rate of people dying of cardiovascular disease has fallen. But continued declines are threatened by rising mortality linked to overweight and obesity – particularly in younger people

Published 4 August 2020

Premature cardiovascular mortality rates linked to overweight and obesity are rising at an accelerating pace in Australia and the United States.

Concerningly, these increases are fastest amongst younger adults who have had a high lifetime prevalence of overweight and obesity.

These findings, from our study published in BMC Medicine, are part of broader research which has revealed slowing declines as well as widening socioeconomic and geographic inequalities in premature mortality in Australia.

Specifically, these latest results explain the contribution of overweight and obesity to the recent slowdown in the long-term decline in cardiovascular mortality rates, which had fallen sharply and driven strong gains in life expectancy in countries like Australia over the previous few decades.

Health & Medicine

Are declines in cardiovascular disease mortality ending?

Premature cardiovascular disease (PCVD) mortality related to overweight and obesity is deaths of people aged 35 to 74 years for whom any cardiovascular disease is reported on the death certificate, along with obesity or any other cause strongly associated with overweight and obesity: diabetes, chronic kidney disease, lipidemias or hypertensive heart disease.

Our study analysed multiple cause of death data from Australia from 2006 to 2016 and the US from 2000 to 2017.

As of 2016 in Australia and 2017 in the US, the PCVD mortality rate related to overweight and obesity was rising at approximately three per cent per annum.

This followed an earlier decline of more than two per cent per annum in Australia and a period of stagnation in the US.

Preliminary data suggest this increase has continued in subsequent years.

We found that 40 per cent of Australian and 50 per cent of US PCVD mortality is related to overweight and obesity – this is about 20 per cent higher than the Global Burden of Disease Study’s estimates of 34 per cent and 41 per cent, respectively.

Meanwhile, PCVD mortality in Australia that is not related to overweight and obesity has continued to decline.

Health & Medicine

World-first test could predict your risk of a heart attack

The key advantage of using multiple cause of death data is the identification of clusters of causes with a common underlying risk factor, such as overweight and obesity.

This not only means policy relevance can be enhanced, but also that mortality analysis can go beyond simply identifying one underlying cause for each death.

The finding that younger age groups in both countries had the fastest rate of increase in overweight- and obesity-related PCVD mortality is of particular concern.

This increase sits at four per cent per annum for males and two per cent for females aged 35 to 44 years in Australia over the period 2006-2016, compared with roughly a two per cent per annum decline in the 65 to 74 years age group.

A higher proportion of deaths of younger age groups also reported obesity on the death certificate.

In both countries, the lifetime prevalence of obesity was highest for the cohort aged 35-39 years and lowest in the cohort aged 70-74 years. In other words, these high levels of obesity in younger age groups are now increasing their risk of premature death.

While mortality from cardiovascular disease is relatively uncommon in these younger age groups, we need to think about the potential impact that their high rates of obesity and overweight will have on PCVD mortality when they reach later middle age where vascular mortality is much more common.

Health & Medicine

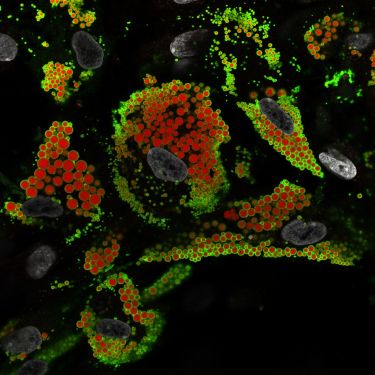

Different fat cell types may be key to obesity

These findings are particularly pertinent for Australia and the US, where close to one-third of the adult population is obese and another third are overweight.

In Australia, obesity is higher among lower socioeconomic areas and outside capital cities. These population groups are experiencing a stagnation of premature mortality rates while they continue to fall in higher socio-economic areas and in capital cities.

Given the likelihood that overweight and obesity-related mortality will continue to rise in Australia, this will more than likely disproportionately affect these poorer population groups and widen mortality inequalities even further.

Much greater efforts across government, civil society and the health sector are urgently needed to reduce the impact of overweight and obesity on the health and survival of Australians.

And the focus must be on dietary change and increased physical activity.

Unfortunately, both Australia and the US (and other countries) have not been successful at reducing obesity prevalence, in the same way that tobacco control interventions have brought about a massive reduction in smoking prevalence.

Health & Medicine

The unhealthy habits killing Australian women

Public health groups like the Obesity Policy Coalition have made recommendations to reduce obesity that include tougher restrictions on junk food advertising to children, adding a levy to sugary drinks, making the Health Star Ratings systems mandatory, developing active transport strategies and strengthening public health education campaigns.

Research from Mexico has already shown that the introduction of a levy on sugar-sweetened beverages in 2014 resulted in a reduction in soft drink consumption.

Separate modelling suggests that this would reduce the number of coronary heart disease and stroke deaths by 11,000 over 10 years, with the greatest relative reduction in death rates at ages 35 to 44 years.

The longer-term implications of high obesity prevalence and the consequent rise in overweight and obesity-related cardiovascular disease in Australia among younger adults are worrying.

But unless there is a substantial reduction in overweight and obesity in Australia and the US – any future gains in life expectancy are likely to be hampered.

Banner: Shutterstock