Edgar Degas: Capturing a world of movement

Degas and the tumult of Paris in the late 1800s

Published 23 June 2016

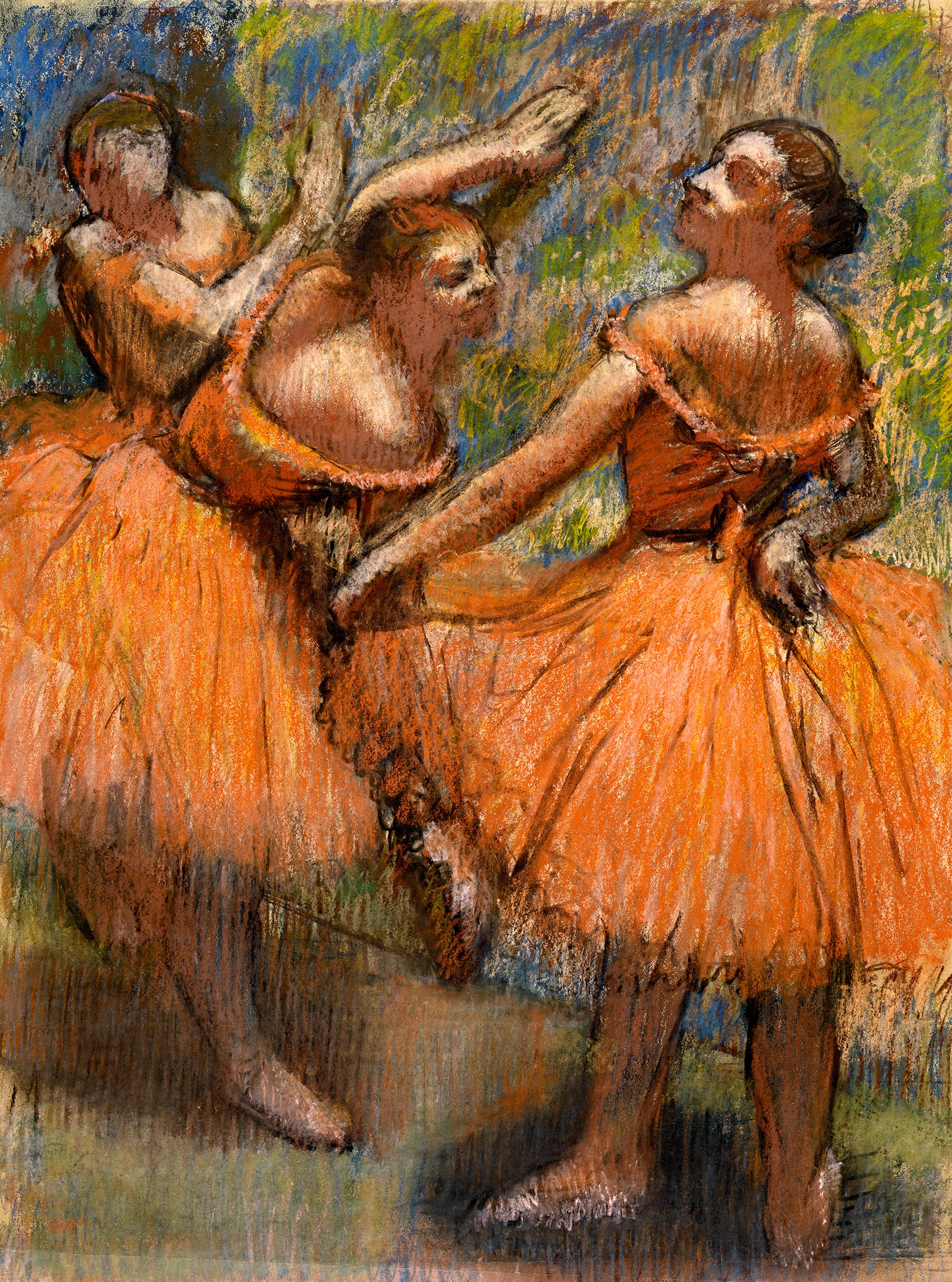

Edgar Degas was a superb draftsman with an extraordinary capacity to capture movement in the human form.

His greatness lies in the application of that skill to the world around him – particularly through images of women at work and leisure, portraits of friends, and studies of the swirling action of ballet and race-courses.

We may owe that contemporary focus to a chance meeting and subsequent friendship with Édouard Manet when the two started talking at the Louvre in January 1862. Degas had had a formal training and planned a career in conventional historical paintings drawn from biblical and classical subjects.

Manet, in contrast, had just started on the sensational Luncheon on the Grass (Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe). The Paris Salon rejected it for exhibition in 1863 but Manet exhibited it at the Salon des Refusés (Salon of the Rejected) later in the year, the beginnings of a dramatic development in European art history, leading to the Impressionist exhibitions of 1874-86. Degas helped organise these exhibitions although personally refusing the label ‘impressionist’ in his typically caustic way.

Degas soon ended his paintings of historical subjects, instead exhibiting the Steeplechase—The Fallen Jockey (1866). Degas became a frequenter of horse-races from 1861 and made a sketch of Manet there in 1865.

The exhibition brings together from international collections the full range of Degas’ astonishing talents, from drawings and engravings to paintings, photographs and sculpture. In partnership with the NGV, the Faculty of Arts is presenting a four-part masterclass series on the life and art of Degas.

Participants will hear lectures and floor-talks from University and NGV experts as well as having special after-hours access to the exhibition.

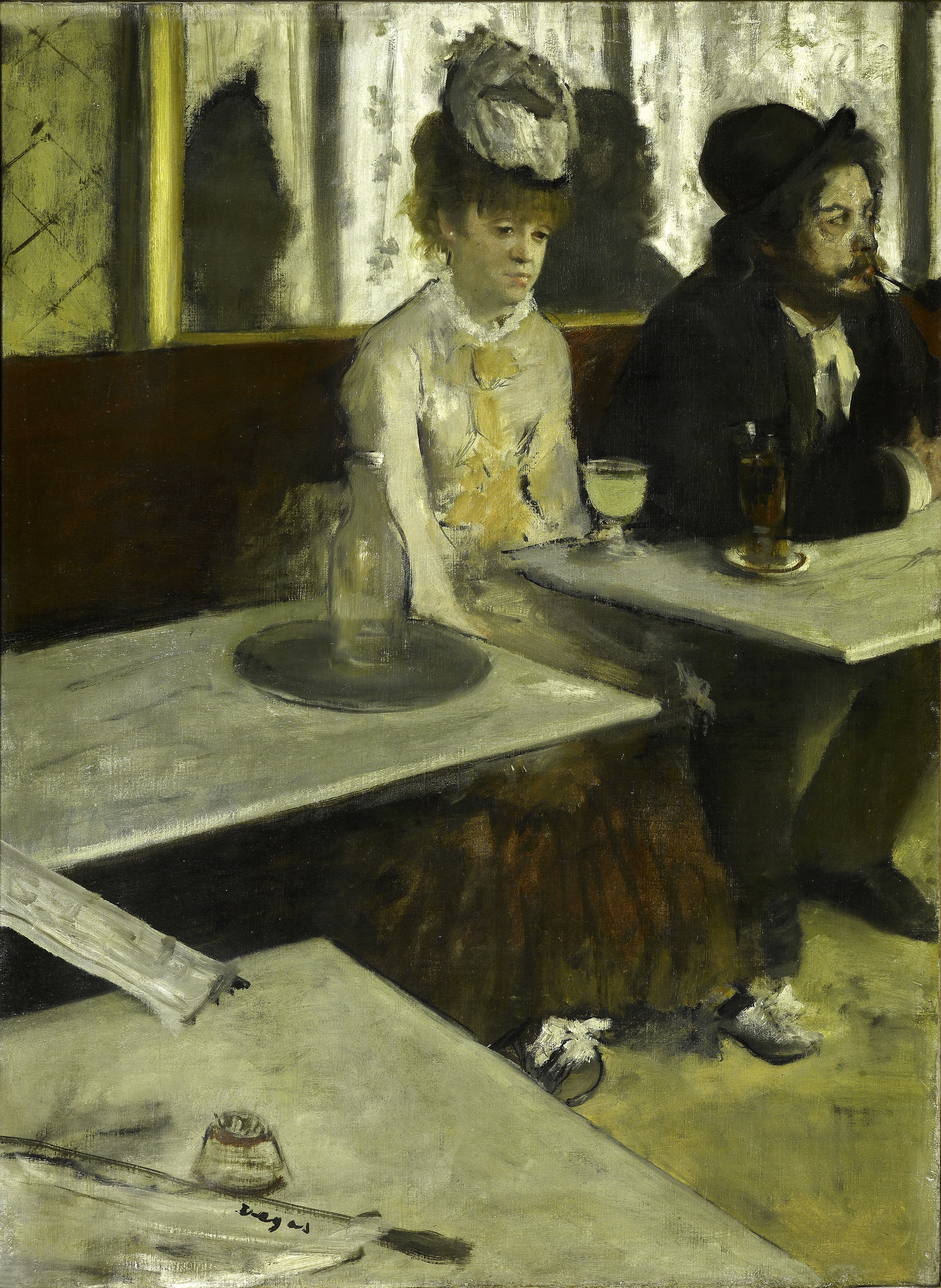

Degas’ long life (1834-1917) coincided with dramatic social change and political instability in the French capital. From fewer than 900,000 people at the time of his birth, the Paris metropolitan area grew to 4.5 million by the time of his death.

The inner city underwent dramatic rebuilding from the congested, medieval neighbourhoods to the boulevards familiar to us today. One of the major motivations for slicing wide boulevards through the city was to facilitate troop movements from nearby garrisons, ending the problem of manoeuvring through twisting, narrow streets at times of insurrection.

As Émile Zola was to capture in his novel, L’Assommoir, the rebuilding of Paris displaced poverty without eradicating it. Many of the poor were pushed into the northern and eastern suburbs not serviced by improvements to the urban infrastructure, such as running water. There was a profound change in the social composition of the central city, its more affluent nature reflected in the new department stores which boomed after 1870, ‘the cathedrals of modern commerce’, as Zola dubbed them in another novel, Au Bonheur des Dames.

Paris was a‘hyper-political’ city: Degas lived through the last French monarchy, two republics, an empire, two revolutions, a military coup, and the first communist regime (in 1871) – but the greatest political change was peaceful. Unlike its predecessors, the Third Republic was to grow from its revolutionary origins in 1870 into a durable democratic régime lasting until 1940.

But its authority was repeatedly challenged by scandals and crises, in particular that following the arrest and banishment to Devil’s Island in French Guyana of the Jewish army Captain Alfred Dreyfus in 1894 for selling military secrets to Germany. By 1899 he had been repatriated and pardoned, but by then the Dreyfus Affair had become an issue of the reputation of the French officer corps, and not until 1906 was he formally declared innocent and reintegrated into the French army.

The Dreyfus Affair was one of the turning-points of modern French history, arraying anti-clericals and civil libertarians such as Zola (whose open letter J’accuse sold 300,000 copies of the newspaper in which it was published) against a powerful coalition of nationalists, anti-semites, and almost all of the media. Degas embraced the anti-Dreyfus, anti-Jewish cause, cutting lifelong friends and becoming a curmudgeonly and lonely old man as his health declined.

Not only were the years of the ‘belle époque’ before 1914 in fact a time of scandal, but they were not at all ‘beautiful’ for masses of working people. On average, French people were better off in material terms in 1900 compared to the time of Degas’ birth, but there is no evidence that differences in wealth had narrowed. There were minimal workplace protections: an 1898 law only limited working hours for children under 18 and women to 11 hours per day.

Since so many prostitutes refused to be part of the regulated policing system of brothels, it is impossible to say with certainty how many women wholly or partly survived in this way. By 1880, there were 140 registered brothels. One aspect of Degas’ greatness lies in his ability to capture the lives of sex workers, as well as of other girls and women in the physically exhausting world of work ranging from ballet to laundries.

Ever since a visit in 1872-73 to his part-Creole brothers who worked in the cotton industry in New Orleans, Degas had worried about his deteriorating eyesight. The final section of the exhibition includes some haunting self-photographs of his own long physical decline.

In 2016, as part of The University of Melbourne’s Learning Partnership with the NGV on ‘Degas: A New Vision’, the Faculty of Arts has collaborated with the NGV to present Melbourne Masterclass: Degas – A New Vision…a new beginning series. This cultural partnership provides a unique opportunity to build on and further develop the rich and multifaceted relationship that the Faculty of Arts enjoys with the NGV.

Cover image Edgar Degas, Rehearsal hall at the Opéra, rue Le Peletier 1872 oil on canvas 32.7 x 46.3cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris (RF 1977) © RMN-Grand Palais (musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski