Education technology, schooling and privacy

COVID-19 has highlighted the increasing growth of education technology or EdTech, but more legal reform is needed for children’s privacy as they learn online

Published 14 May 2020

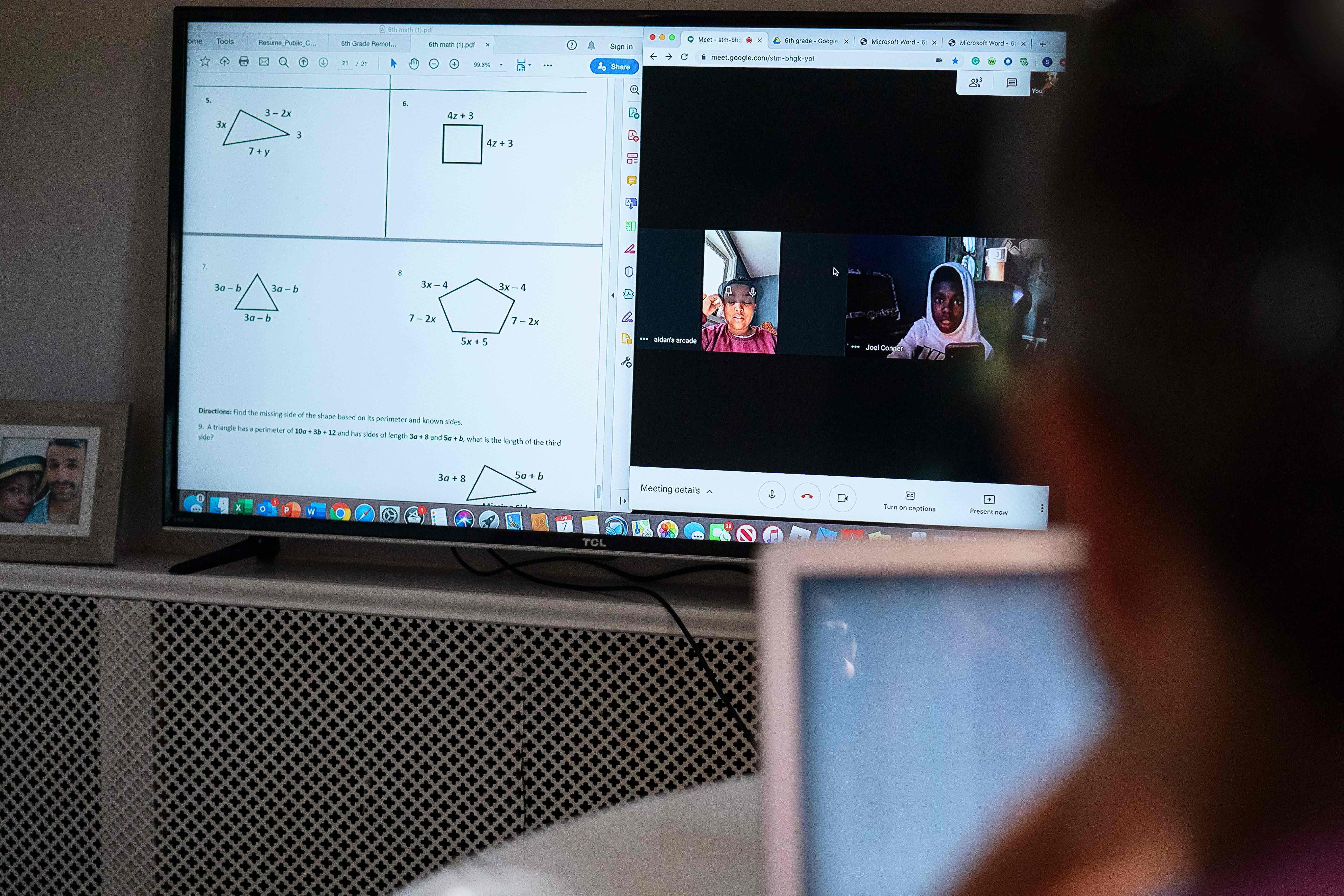

The COVID-19 outbreak has rapidly accelerated how much schools rely on online learning.

The move has raised a range of issues – particularly digital privacy and security of information.

Managing these security and privacy issues is the responsibility of regulators, schools and parents, but the law still lags behind in providing the kinds of protections that young people need to navigate online learning safely and securely.

Education Technology, or EdTech, is actually a booming industry and before the coronavirus pandemic, students were already using a range of devices and software to assist with their learning.

Many state education departments and schools already have guidelines and practices in place in relation to vetting software. For example, the eSafety Commissioner has risk-assessment resources including online safety assessment tools and checklists to screen new technologies, and states like Victoria have their own tech support resources.

But to facilitate extensive remote learning for students, particularly during COVID-19, it’s inevitable that additional software and apps will be used, often untested. As a result, the privacy of children and young people is left exposed if schools and departments don’t properly consider the risks involved in using these.

The issues around introducing new technology to schools aren’t new.

In 2018, a trial of facial recognition software to record school attendance in Victorian schools was shut down due to privacy concerns. The risk to student privacy and the concept of constant surveillance outweighed any benefit of the software.

However, at the moment, schools and education departments may not have the capacity or the time to consider in detail the privacy and surveillance implications of additional software – which may be collecting an immense amount of personal audio and visual data.

Internationally there has been a gathering momentum behind strengthening privacy laws and data protection regimes that pre-dates COVID-19.

But, despite these calls for law reform, Australian federal privacy laws still lag behind.

In addition, schools find themselves in a complicated legal landscape, having also to comply with state privacy and data protection regimes where they have them – making a unified approach difficult.

During 2019, calls for law reform in this area increased in Australia, especially in relation to digital platforms.

The Digital Platforms Report, released by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), comprehensively looked at the issues involved in this digital age.

Notably, it recognised additional concerns for children, stating that children were at a “higher risk from the negative effects of information disorder than others”.

Information disorder refers to the impacts of inaccurate or deliberately misleading information and dis-information.

Information and media literacy are vital as many young people today obtain the majority of their information online. This skill becomes even more essential with remote learning and an increased amount of time spent online.

Among the ACCC’s 23 recommendations in the Digital Platforms Report was a call for more strengthened consent and default ‘opt out’ requirements, specifically for children. However, strengthened consent requirements aren’t enough to deal with the range of data practices we are seeing.

Furthermore, if schools require students to use particular software for their learning, it seems even more unlikely that informed consent is really given freely by the student.

Education

The world is a classroom

Some baseline protections should also be considered around limiting specific data processing practices to only what is needed to provide the service.

The ACCC also recommended “additional restrictions on the collection, use or disclosure of children’s personal information for targeted advertising or online profiling purposes and requirements to minimise the collection, use and disclosure of children’s personal information”.

Certain practices would simply be banned, including perhaps some targeted advertising and other profiling of students, and a sufficiently resourced regulator could ensure compliance.

Empirical work has shown again and again that teens do care about their privacy. They will continue to do so as they use educational technology and learn online.

And the use of technology to learn online and the issues it raises isn’t simply a binary choice between education or privacy.

More focus should be on continuing the momentum for the legal reform needed in this area.

By prioritising children and young people’s privacy as they learn online, we can minimise any long-term impacts of this style of education and ensure that their best interests are protected now and into the future.

Banner: Getty Images