Finding the Hidden Hellenism in Melbourne

Take a tour through Melbourne with a Greek lens and discover the rich Hellenic influences that shape the city

Published 1 November 2016

Melbourne is the city with the largest Greek population outside of Europe.

Since the earliest instances of Greek migration in the mid-19th century, the Greek community has been a great contributor to the richness of Melbourne. Lonsdale Street, in the heart of the city, remains an important precinct for the Greek community.

But what many people may not realise is how much Hellenic culture is embedded independently of the migratory trend, shaping the very fabric of the city. The Greek influence on Melbourne began much earlier.

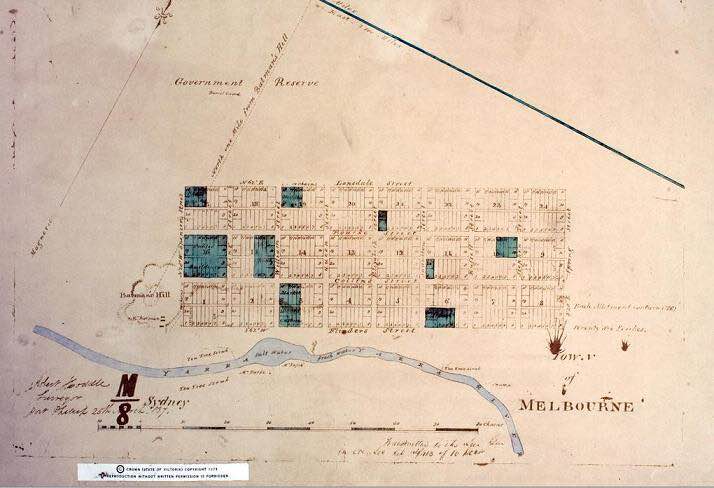

For example, the gridded layout of Melbourne’s central business district reflects Hellenistic urban planning traditions. The Hoddle grid, named after its planner Robert Hoddle, was laid out in 1837, only two years after the city was founded by Batman and Fawkner.

The intention was to create a sense of order and stability to guide the new town through its development as a colony. Hoddle’s own city grid mirrors the Hippodamian Plan, named after Hippodamus of Miletus. Throughout the 5th century BCE, Hippodamus imposed grid plans upon a number of new city foundations, including Piraeus, the famed port city of Athens. His plans were taken as the ideal form for a city, and great conquerors like Alexander the Great used them to establish a number of colonies; the city of Alexandria founded by Alexander in 331 BCE is distinguished by a grid system.

Hellenism played a part in many other steps of Melbourne’s foundation as a city. Laid into the Hoddle grid were a number of Greek-inspired public structures symbolising the sophistication of the new state and its lineage to its European cultural predecessors. The following four buildings – the State Library of Victoria, Parliament House, Customs House and the Melbourne Mint incorporate Grecian orders and reference the neo-classical style marking key locations on the Hoddle grid.

The state library of victoria

A leading figure in some of Melbourne’s most recognisably neo-classical inspired structures of the mid-1800s was Joseph Reed. Reed designed the Melbourne and Geelong Town Halls, but he is better known as the architect whose design won the competition for the Melbourne Public Library, now the State Library of Victoria, set out by Lieutenant-Governor La Trobe in 1854.

The exterior ornate Corinthian columns support a heavy pediment much like they would have at the now ruined Temple of Olympian Zeus at Athens. In contrast, Queen’s Hall, the Library’s original reading room, is lined with elegant Ionic columns, making it more akin to an inside out temple of Athena Nike in Athens.

Parliament house

The majestic Parliament building, begun only a year after the State Library and located on the hill at the eastern edge of Hoddle’s grid, reflects the more austere Doric order. The commission, originally given to colonial engineer Charles Pasley, was passed on to Peter Kerr and John George Knight. The exterior evokes a renaissance palace façade brimming with classical references: columns, pilasters, triglyphs, metopes, festoons and relief cuttings that mimicked the Athenian Parthenon in a nineteenth century setting.

The interior meanwhile showed a sumptuous classicism of tiered column orders, gold leaf decorations and Greco-Roman inspired statuary. This all came together to create the composite temple come Palladian villa that makes up the Parliament building today.

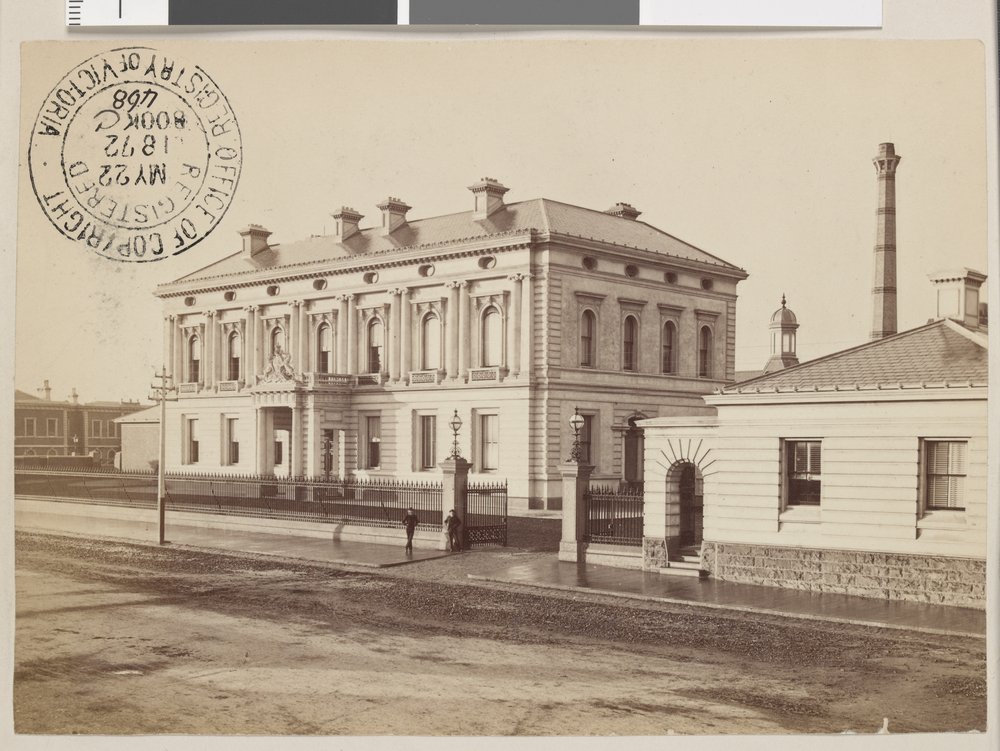

Customs house

Another building designed by Peter Kerr that drew its inspiration from both ancient temples and elite Renaissance living was his Customs House, located just north of the Yarra River. While on the outside this structure looks more like a 16th century Roman palace, the columns and architraves were intentionally based on the Erechtheion, a temple to the epic hero Poseidon located on the Athenian Acropolis. The Customs House controlled trade and immigration until 1965. Since 1998 the site has housed the Immigration Museum. Whilst the old exterior displays the influence of the Hellenising architecture the new interior exhibits speak of a different type of Greek migratory influence, and one that has greatly enriched multi-cultural Melbourne.

The melbourne mint

A final early metropolitan building worthy of mention that completes this clockwise traversal of the city is the Renaissance Revival style former Melbourne Mint (1872) on Williams Street. While the structure is more Roman than Greek, modelled on Raphael’s Palace in Rome, the current use of the old administrative offices gives the building a new role within the Greek culture of Melbourne. Since 2007 the complex has housed the Hellenic Museum, an institution founded by Spiros Stamoulis to safeguard and promote Hellenic culture past and present. In 2013 the Museum engaged in a landmark partnership with the Benaki Museum in Athens, allowing for a loan of unique artefacts spanning 8000 years of Greek History.

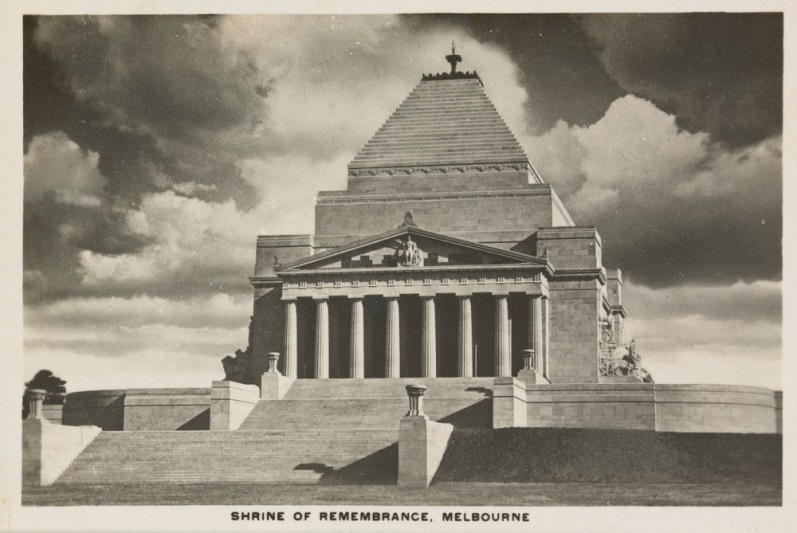

Occupying key points within the Hoddle grid, these four monuments defined the character of the early city, moulding Melbourne into an ordered and cultured centre of the new world. While the Hellenistic fervour of Melbourne’s first administrators tapered off with the emergence of a new local form of Australian nationalism, there were still some structures that adhered to a classical aesthetic, most prominently the Shrine of Remembrance, a structure built to commemorate the Australian lives lost in the Great War.

The Shrine directly emulates the Tomb of Mausolus at Halicarnassus, once again drawing on the distant solemnity and grandeur referencing the classical civilisation of the ancient world.

Monuments such as this show the continued popularity of classical motifs, and their integration within the modern city to create an interesting juxtaposition of a country that stands with one foot firmly planted in the past, and another leaping (looking) eagerly into the future.

The University of Melbourne’s Ian Potter Museum of Art is a more recent example of this evolving architectural tradition. A sleek modern building, designed (1998) by the Greek architect Nonda Katsalidis, it houses both the oldest collections that the University possesses in the form of the Classics and Archaeology Collection and cutting edge works by modern artists. The Potter façade tells the story of classical displacement through Christine O’Loughlin’s sculptural mural “Cultural Rubble” (1993). Fragments of the Venus de Milo and the Winged Victory of Samothrace, the Discus Thrower and the Delphic Charioteer, highly decorative Greek urns and vases, and a monumental Doric column, form some of the individual elements constituting the panels of Cultural Rubble. The mural was created through a process of casting sculptures from earlier casts of classical pieces. This shows, in full sculptural form, the distance of the classical past from our own Australian present, but also the exceeding importance it has had within the physical and cultural formation of Melbourne and the place it still holds in the city’s collective consciousness.

The Hellenic Museum is an official partner of the Faculty of Arts.

Banner Image: Shrine of Remembrance at night/Wikimedia Commons.