Health & Medicine

The science behind the search for a COVID-19 vaccine

Given the implications for potential take-up of a COVID-19 vaccine, it’s important to unpack religious as well as the general ethical concerns from using human cell lines

Published 3 September 2020

On 20 August 2020, three prominent religious leaders in Australia wrote to the Prime Minister to express concerns about the ethical dilemma associated with calls to make vaccination for COVID-19 mandatory.

This followed the announcement that the Australian Government had signed a letter of intent to secure supply of the AstraZeneca/Oxford University COVID-19 vaccine – should the current clinical trials prove successful.

The central concern is that the production of the vaccine uses a cell line – HEK-293 – that is “cultured from electively aborted human foetus” and that the Australian Government should support supply of an alternative “uncontroversial” vaccine if mandatory vaccination for COVID-19 is to be introduced.

Health & Medicine

The science behind the search for a COVID-19 vaccine

Given the implications for potential take-up of a vaccine, it’s important to unpack this concern as well as the general ethical concerns from using human cell lines.

Manufacturing of the ‘Oxford’ vaccine involves human kidney cells. These cells are used as “factories” to make the component of the vaccine that carries genes from the SARS-CoV-2 virus with the aim of triggering an immune response to protect the recipient when injected.

The type of cells used are descendants of cells first obtained in the early 1970s, from a foetus which was probably electively aborted (although records have now been lost).

These cells were cultured in the laboratory to produce what is called a ‘cell line’, a population of cells that have adapted to grow continuously in culture while retaining uniform characteristics.

Once created, cell lines are usually shared with researchers in different laboratories and referred to by a simple reference code. In the case of this foetal cell line it was called HEK-293.

Health & Medicine

A remedy for false COVID-19 cures?

Even though the descendants of foetal cells are used to produce the vaccine, the actual vaccination does not contain any foetal cells, or pieces of foetal DNA.

This cell line, and others like it, are commonly used in medical research. Indeed six of the COVID-19 vaccine candidates in development across the globe use human foetal cell lines.

Foetal cells derived from elective terminations of pregnancy have been commonly used in scientific research since the 1960s.

Their unique properties, such as an ability to be grown easily in the lab into cell lines, and the extensive knowledge about these cells gathered over decades of research, has seen them used to manufacture many vaccines, including those commonly used against rubella, chickenpox, hepatitis A, and shingles.

Again like in the production of the Oxford vaccine, there is no residual foetal cells or DNA in the actual vaccines.

Foetal cells have also been used to make approved drugs against diseases including haemophilia, rheumatoid arthritis, and cystic fibrosis and to study infectious diseases like Zika and HIV.

Health & Medicine

Vaccination: A numbers game that adds up

It is important to clarify that while foetal cells are sometimes referred to as ‘embryonic’ cell lines, this should not be confused with the use of human ‘embryos’ or creation of ‘embryonic stem cells’.

Foetal cells are obtained from donated tissue following termination of pregnancy or spontaneous miscarriage, while embryonic stem cells are obtained from donated human embryos originally created in the course of infertility treatment at an IVF clinic.

The term ‘embryonic’ can refer to a stage of development both before and after a pregnancy is established.

HEK-293 cell line may be correctly described as being from ‘embryonic kidney cells’ but is quite different to the use of human embryos to make an ‘embryonic stem cell line’ that could be used in research to understand kidney disease or how kidneys develop.

The use of human embryos in research is highly regulated in Australia and elsewhere across the globe. While advances in stem cell research have reduced the need for foetal cells in certain areas of research, there remains a clear need for foetal tissue research.

The letter to the Prime Minister cites concerns that using products from the HEK-293 line amounts to benefiting from an elective termination, and therefore makes one complicit in a moral wrong.

Health & Medicine

Your protective Igs: The major focus of COVID-19 vaccines

This is only a concern for people who believe terminating a pregnancy is a moral wrong. This position would have far-ranging implications for public health, beyond the use of the Oxford vaccine.

Many currently available vaccines, and some other COVID-19 vaccine candidates, are produced using foetal cell lines.

More fundamentally the use of foetal cells lines is a ubiquitous part of medical research, leading to many techniques and drugs that are commonly used in medicine and have contributed to advances that have saved many lives.

Even those who have no moral objection to elective termination of pregnancy may have other concerns about the use of human or animal cell lines.

Ethical standards have improved greatly in the last few decades, and we need to confront some ethically suspect practices of the past. But one way we should respond to past bad practices is to learn from them and improve our standards.

In Australia, research using foetal tissue is subject to careful oversight under the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (National Statement), which exemplifies the values of respect, research merit and integrity, justice, and beneficence.

Politics & Society

Cell sell: The ethics of the transnational human tissue market

The National Statement acknowledges that human research carries a potential risk of harm, discomfort and/or inconvenience for participants and/or others and therefore requires that the potential benefits of the research justify any risks involved.

It also requires that those who conscientiously object to being involved in conducting research with foetal tissue are not compelled to participate or put at a disadvantage because of their objection. This concession reflects the value of respect for human life and the beliefs of those involved in research.

While one of the letter’s authors, Sydney’s Archbishop Anthony Fisher, has subsequently stressed that he does not think that it would be “unethical to use this vaccine if there is no alternative available”, and that he won’t be critical of anyone who uses the vaccine.

His call for “ethically untainted alternative” might be difficult to meet given the long and deep role that foetal tissue has played in medical research.

It’s unlikely that any COVID-19 vaccine will be entirely free from the use foetal cell lines, as some knowledge gained from those cell lines will go into any vaccine that is created.

Health & Medicine

Our ‘killer’ cells’ role in life-long flu vaccine

While this issue may not be easily resolved, it is important to continue discussing ethical issues as we race to develop safe and effective treatments and/or vaccines for COVID-19.

As acknowledged in the National Statement, the risks and benefits of human research must always be considered to promote ethically good research.

The development of a safe and effective vaccine for COVID-19 carries significant benefit for the community, thereby promoting the values of research merit and integrity and beneficence.

Another core value in the National Statement is justice, which includes ‘procedural justice’ (fair treatment in the recruitment of participants and the review of research) and ‘distributive justice’ (fair distribution of the benefits and burdens of research).

As new vaccines are developed, it will therefore be important to uphold rigorous ethical standards in both laboratory and clinical research and ensure equitable distribution of the vaccine on a global scale.

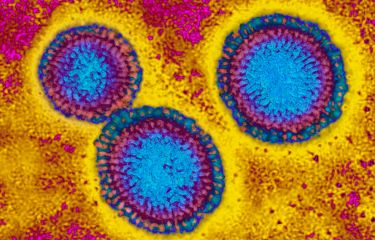

Banner: Getty Images