Games don't build communities – communities build games

From creators and designers to researchers and players, gaming communities prove that the real value of games lies in the worlds these communities build together

Published 7 October 2025

It’s September 2025. The Game Worlds playable exhibition is open at Australia’s national museum of screen culture, ACMI.

The exhibition presents 30 iconic games spanning 50 years of play – a testament to the scale and lineage of game communities in Australia.

The exhibition explores how both developers and players shape games, and in turn, shape the people and communities who play them.

It’s an insight into the cultural impact of games in Australia.

But, as gamers, we tend to think of ourselves as outsiders. Many people who play games don’t want to identify as gamers.

Research suggests that this is because we’re embarrassed. People don’t want to be seen to engage in play – an activity that is unruly, pleasure-driven and unproductive – because it is incongruent with the social identity of an appropriately behaved, norm-abiding adult.

This anxiety leads us (as scholars) to frame games by their economic value and, as designers, to emphasise their potential for education, collaboration or creativity.

We can’t seem to shake the lingering perception of games as frivolous, nor the image of a gamer as a teenage boy.

This is despite consistent data that shows upwards of 80 per cent of Australians play video games – double the number who follow the AFL– and that 52 per cent are women.

Alongside digital games, tabletop games like Dungeons and Dragons (D&D) have never been more popular. Online shows like Critical Role – a D&D live play broadcast on the streaming platform Twitch.TV – has resulted in an increasing number of people playing the game.

People want to play games. And they want to play games together.

The making of games

Melbourne is frequently referred to as the “capital of Australian video game production”. This, despite Adelaide’s recent hero moment with the release of the highly anticipated Hollow Knight: Silksong.

But it’s because the communities that make up the Australian games industry are most prevalent (or perhaps visible) here.

However, what we call ‘the industry’ is better understood as a constellation of informal community events that facilitate the making of games.

These communities of game makers often express contradictory norms and practices to those of the formal parts of the games industry, particularly around secrecy and gatekeeping.

Longstanding communities like the Freeplay Independent Games Festival are a prime example of this.

Freeplay demonstrates that the community’s values of inclusivity and accessibility are suffused through its organisational structures.

And it’s these values that have allowed the festival to operate for two decades as a community-centred sanctuary for game makers – a space where knowledge and expertise are shared.

Communities like this one are a melting pot of folks interested in games – and while they primarily serve designers, they draw in many games’ researchers too.

The local and the ephemeral

It may come as no surprise that the people who research games like to play them.

The Melbourne Academic Games Play and Interactive Entertainment (MAGPIE) initiative is a community of games researchers at the University of Melbourne.

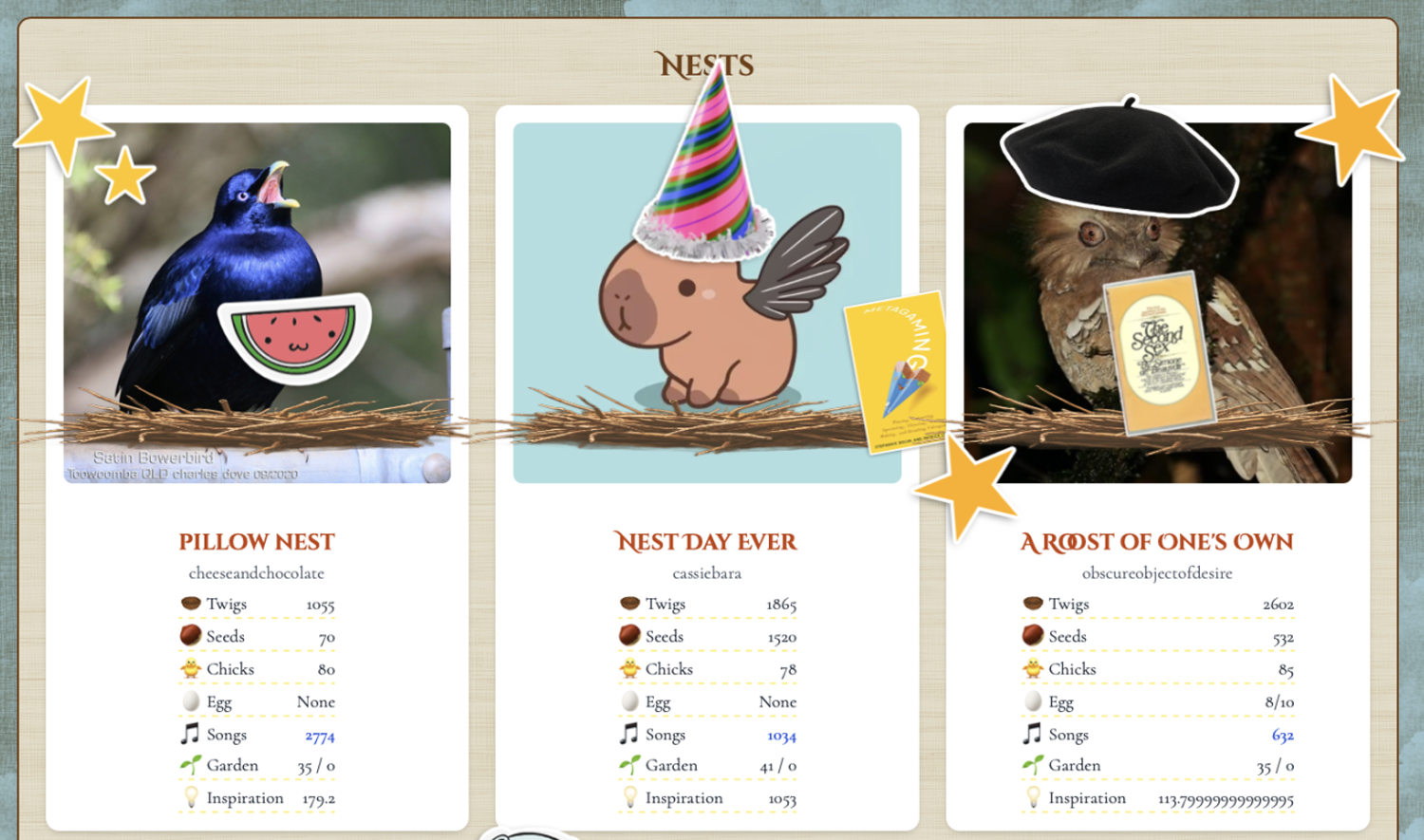

The MAGPIE Discord server is home to a private custom game built by creative developer and interaction designer Cuauhtemoc Moreno.

Bird-RPG lets players embody birds in collective rituals, with gameplay mechanics built around the MAGPIE community itself.

It’s a game that emphasises social connections generated through these communal rituals – in this case, the ritual of regular and shared play.

Its design focuses on the small, the local and the ephemeral – in contrast to the industry’s preoccupation with scalability. The game's success can be measured by the quality, rather than the quantity, of connections it fosters.

Something that again, is a measure of success that a ‘games industry’ (which sees players as part of a market) would not value in the same way.

Politics & Society

Video games are building worlds beyond the laws of physics

Participating in an unfolding narrative

While communities of designers sustain game making and researchers critique games, players are members of communities that, through their commitment, become co-creators of the games they play.

The regular players of live action role-playing (or LARP) games in Melbourne are just one example of this.

LARP invites players to become a character in a fictional setting.

A small LARP, like those designed by Melbourne not-for-profit group Caligo Mundi, will host between 20 and 50 players, while Melbourne Megagames’ First Contact brought together 200 players at St Kilda Town Hall in late 2024.

Later this year, around 200 players will gather in the Melbourne suburb of Warrandyte to participate in the final instalment of A Dance of Ribbons – the first LARP in Australia to receive government funding as a recognition of its artistry, significance and scale.

Although generally designed by small teams, the experience of a LARP is a result of the cumulative creativity of every player. It’s not a product of a designer that players then receive.

Rather, players co-create the game through play.

By participating in an unfolding narrative and making contributions to a shared world, LARPs are often transformative for players, creating lasting connections that transcend the game itself.

Many communities anchored in specific games endure in some form long after a game has ended. To make and to play games is to make worlds, and this changes our everyday world in material and relational ways.

Arts & Culture

All the world’s a game (and we are all players)

This is the central thesis of the Game Worlds exhibition. That games are sustained by communities.

These are people who will continue to play D&D and Hollow Knight for 50 years into the future.

Whether it’s industry scenes, research collectives or player communities – the fabric of game culture is its people.