Arts & Culture

How the far right weaponised gamers and geek masculinity

By letting players experience racism and decide how to react, games can create an emotional connection that sparks genuine change

Published 7 October 2025

“If people are smart enough to go to university, they are smart enough to learn a name they're not used to hearing.”

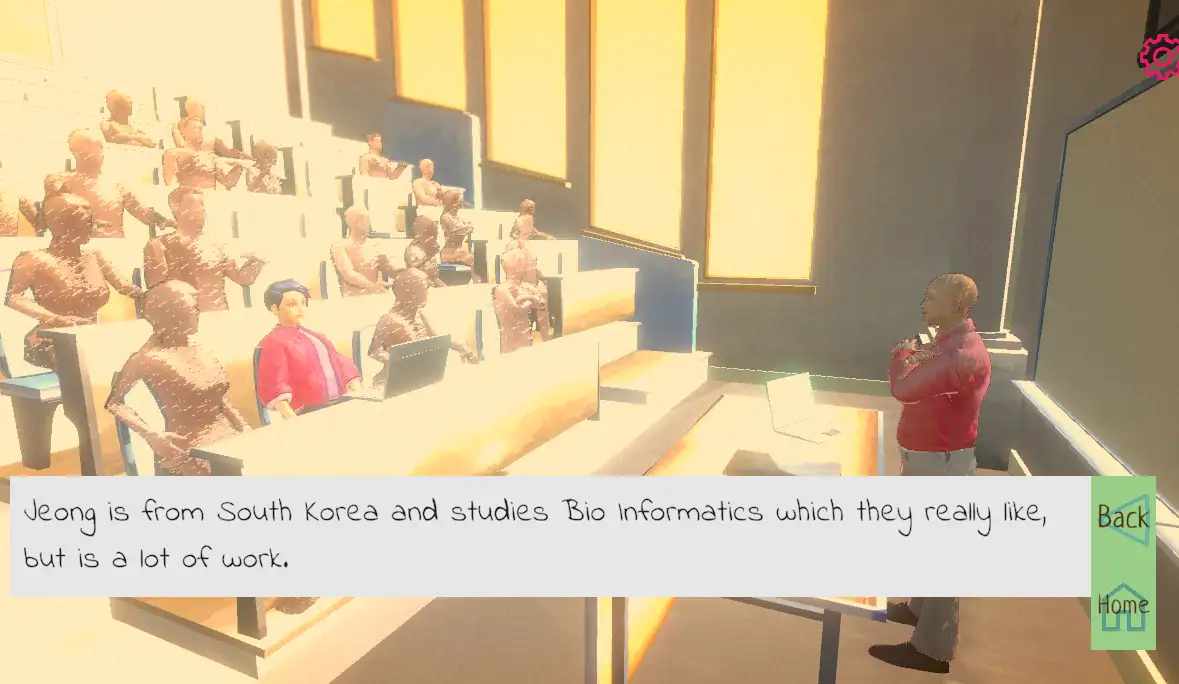

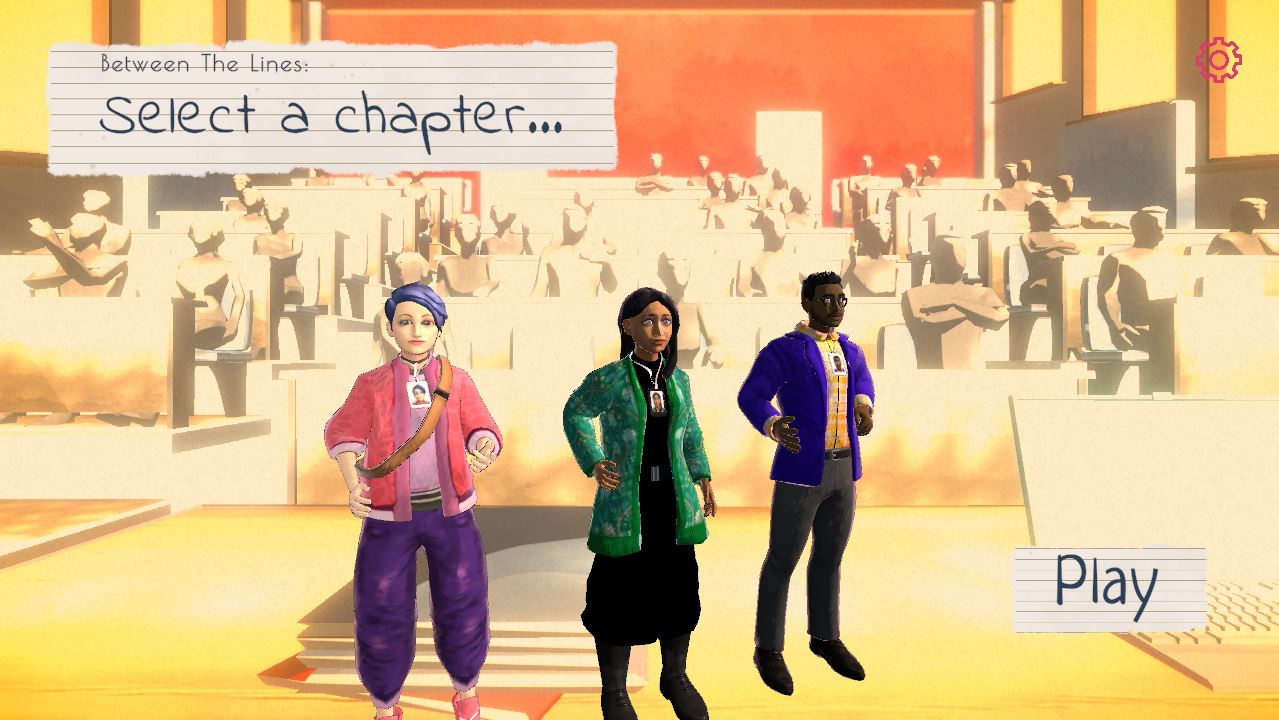

These words belong to Jeong, a character in Between the Lines, a game that allows players to experience the frustration, disappointment and continued cycle of everyday racism.

Jeong’s story, titled Not my name, offers an insight into what it feels like to have your name mispronounced and misspelled continuously.

The University of Melbourne Student Union (UMSU) report on racism (2023) mentions this as an ongoing issue – one that affects students’ wellbeing and sense of belonging.

As someone whose name was mispronounced at my PhD ceremony, this resonates deeply with me.

Hence, the effort to develop an anti-racism interactive resource like Between the Lines.

Funded by the Anti-Racism Hallmark Research Initiative Interdisciplinary Seed Funding Scheme, this game was developed by a multidisciplinary team of academics, game developers and artists.

Arts & Culture

How the far right weaponised gamers and geek masculinity

It has three characters – Jeong Eun-Kyung, Darakshan Khawaja and Khalid Izebboudjen.

Each character represents a university student at a different stage of their academic journey – and each has their own story arc and issues to deal with.

The game narrative draws heavily on the lived experiences of students captured in the above-mentioned UMSU report.

Anti-racism is a big word in higher education. It's a verb that wants to fight the disease of racism.

The University of Melbourne has an Anti-Racism Action Plan, but how do we ensure that our relationship with anti-racism isn’t performative and has a genuinely transformational impact?

Between the Lines is designed as a workshop tool that offers a nuanced understanding of everyday racism, embedded deeply in our systems.

Some of these we are aware of and others we are not.

The game doesn’t stand alone – it needs to be scaffolded by a broader, layered conversation.

The purpose of these workshops is to generate reflexive conversations around anti-racism in a genuine, empathetic way.

It is a smart, interesting, and fun way of sparking those uncomfortable conversations that could lead to meaningful policy changes and systemic transformations.

There has been much written about the power of games in developing empathy.

Arts & Culture

Games don't build communities – communities build games

Games, especially digital games, can create an interactive resonance with the character’s identity as gamers own that identity by controlling the character and through deep engagement with the narrative.

The godfather of games studies, Dr James Paul Gee, has a name for this ‘unique perspective-taking’ phenomenon – ‘projective identity’.

It's crucial in creating gaming attributes, like persistence, resilience and problem-solving.

One of the earliest games that captured my heart is Darfur is Dying (2006).

The story is simple.

You are a refugee trying to fetch water in Darfur, Sudan, but you are unable to because you get captured soon after you leave your house.

This is a powerful example of how games can develop our relationship with an issue. Playing the game increased my understanding and emotional connection more than merely reading.

I could feel the fear, the determination and the hopelessness.

However, just creating empathy doesn’t lead to transformation.

Real transformation requires attitude and behavioural change.

Sustainable empathy, one that requires an emotional response strong enough for us not just to feel, but to remember how we felt, needs persistence and resilience.

This is where the power of games comes in.

Politics & Society

Video games are building worlds beyond the laws of physics

Imagine engaging in a range of different kinds of games – a sort of ecosystem of games – tackling anti-racism from different perspectives.

A series of game-based workshops to develop skills that enable anti-racism activism and leadership.

There's an emergence of games that target crucially important issues of contemporary times. The brilliant game designer and researcher, Jane Mcgonigal, has been advocating about the power of games for change for over a decade and a half.

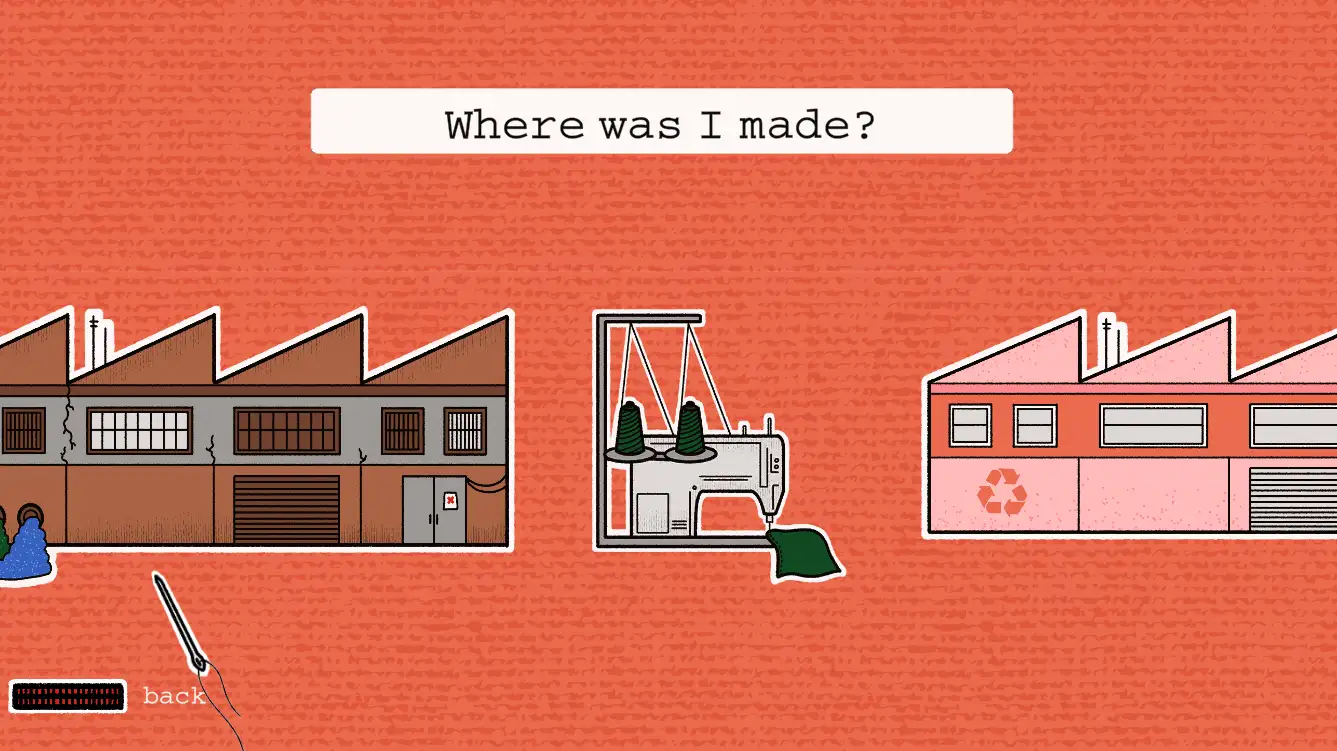

For example, Threads is a game that requires players to engage with sustainable fashion. The gameplay moves through design, manufacturing and distribution.

It also covers the end-of-life scenario for fashion items. It's free and comes with a list of resources if players want to learn more.

Another game, Terra Nil, allows players to rebuild a planet’s ecosystem, shovel by shovel.

Gamers convert a wasteland into grassland, purify water and create liveable conditions for wildlife.

While doing so, they learn about healthy ecosystems and processes.

Now imagine playing these two games while actively learning about the climate crisis, sustainability and consumerism?

This is what I mean by an ecosystem of games, with overlapping themes and gameplay, scaffolded by workshops and in classrooms.

In Between the Lines, one character, Khalid, sees some students being recruited for cultural workshops, despite their discomfit.

Khalid’s gameplay allows players to choose how they react. It might be doing nothing, dealing with it informally, lodging a formal complaint, taking to social media or even legal activism.

The game prompts players to think about what they would do in a similar situation.

Anti-racism is just one example of how games can inspire change.

Games are powerful tools that are employed to slowly create conversations. When these conversations get to a point where attitude and behaviour changes, a small pocket of transformation is created.

In the words of el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz, also known as Malcom X: “If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six inches, there's no progress. If you pull it all the way out, that's not progress.

“The progress is healing the wound that's below, that the blow made. And they haven't even begun to pull the knife out, much less pull, heal the wound ... They won't even admit the knife is there.”

Jeong’s experience of the misspelling and mispronunciation of their name might not be an actual knife, but it stabs. It wounds.

Through innovative design and engaging storytelling, games can create conversation about the knife and further conversations about how to heal the wound.

Once the conversation touches our hearts, the healing process will begin.

To organise a workshop or for any further information, please contact Wajeehah at wajeehah.aayeshah@unimelb.edu.au.