Arts & Culture

Provocative women in cinema

Researchers are using cultural data to highlight the obscured history of Australian women artists, revealing gender disparities and opportunities for positive change

Published 7 March 2023

Gender gaps, biases, and exclusions have always haunted the arts.

Despite its otherwise progressive reputation, the arts and cultural sector remains a problematic industry when it comes to the relationship between labour and gender.

From studies of discrimination around the value and creators of artworks to the disproportionate representation of women artists in major Australian galleries, there is consensus among scholars, economists and employment experts that gender remains a significant barrier in contemporary cultural activity and employment.

Our project, the Australian Cultural Data Engine, is employing historical and contemporary data about artists’ career spans, professional roles, networks, training, prizes and other categories to deliver new insights into the scope, length and influence of women and gender-diverse artists’ careers.

The aim of this is to use cultural data to generate better awareness around the nature of artists’ careers, inform policy development in the cultural sector and contribute to important conversations about funding for the arts.

Arts & Culture

Provocative women in cinema

Research conducted in 2020 found that even after allowing for a range of differences between men and women artists, the gender pay gap in the arts is likely more pronounced than in other areas of society.

Brazilian arts manager and researcher Beth Ponte observed in 2021 that some factors unique to the cultural sector make gender inequality even more complex and multifaceted than that of other industries.

The irregular seasonality and out-of-hours work of many performing arts projects disproportionality disadvantage women who are already burdened by an unequal share of domestic tasks.

More recently, in December 2022, the Culture and the Gender Pay Gap for Australian Artists report took additional cultural factors into account and found that female artists with English as a second language experienced an even greater income disparity.

However, much of the data available remains fragmented, out-of-date, or inaccessible. Our research goal was to use information collected by artists and the artistic community to enhance our understanding of gendered labour in the arts.

Arts & Culture

The modern women of Australian ballet

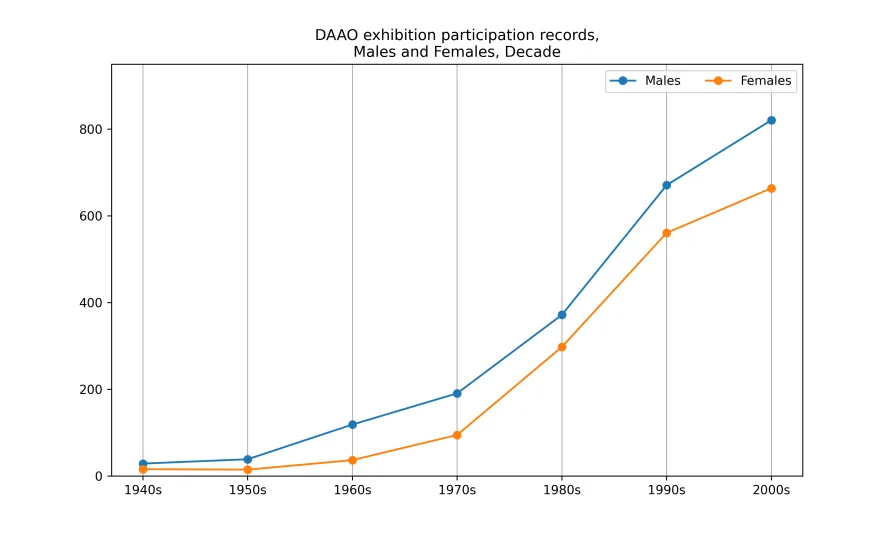

Using data from Design & Art Australia Online (DAAO) to show exhibition participation rates for males and females over time (aggregated into decades) we can see that even after the feminist revolutions of the 1970s, males participated in 12 per cent more exhibitions than females, although the proportional gap has continued to decrease slightly in recent decades.

The DAAO database, with its founding contributions from the feminist art moment, also provides a valuable source of information for examining the dynamics of gendered labour in the arts in the post-war period.

With this data we can ask questions like: When does an artist’s career begin, or end? Are artist occupations gendered, and if so, what impact does that have on a career?

The number of exhibitions that men and women artists have participated in over their careers provides a clearer view of other factors that might influence inequality in income and recognition, including age, location of work, place of birth and institution of artistic training.

We can also examine the relationship between prominence in exhibitions and the value of works available for sale by gender.

Sciences & Technology

The women putting the intelligence in artificial intelligence

Interestingly, we find that the category of simply ‘artist’ is too broad for meaningful analysis, even within a single sector. For instance, a visual artist might be a designer, a children’s book illustrator and a puppet-maker at various points in their career. In the performing arts, a stage manager might also have been an actor, or later become a director.

Women artists frequently hold multiple employments throughout their careers. This pattern, formerly implicit, reveals how women tend to maintain more diverse role profiles over their working lives, suggestive of a widespread tendency towards females holding ‘portfolio careers’.

The term ‘portfolio career’ is often used disparagingly, by way of comparison with employment that is long-term and consistent.

However, multiple role types occur across more fields of artistic and cultural employment, including in architecture; a fact that must be analysed in relation to functions such as gender, metadata definitions or specific industry types.

For instance, visual artists tend to remain an artist until they die, and even afterwards when a retrospective is curated. In contrast, performing artists often announce the end of their stage or film career with a ‘last performance’.

Harnessing this biographical lens across various data groups also gives us insight into other factors that might affect the roles that women artists hold, including maternity support, awards, funding, and networks of collaboration.

Politics & Society

AI, automation and women

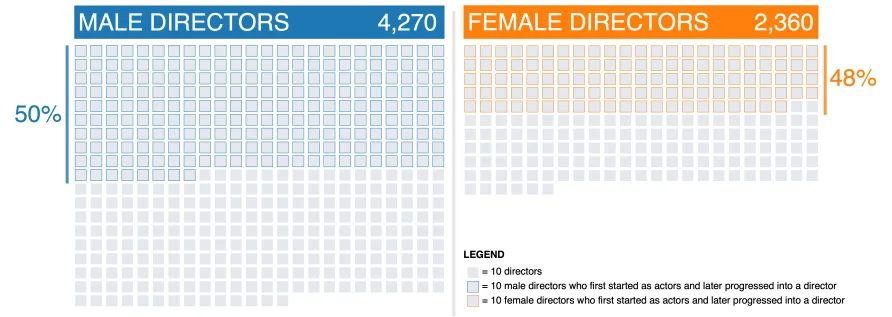

We looked at the time it takes actors to progress into directors and found a current gender disparity among directors, with a significantly higher number of male directors – 4270 – compared to their female counterparts – 2360.

Interestingly, around 50 per cent of male and 48 per cent of female directors began their careers as actors before progressing into a directorial role.

However, these results only scratch the surface of the issue. There are also many people who become directors without ever having had another role in the performing arts, often starting their theatre careers at school or university and immediately entering the industry as ‘directors’.

We have undertaken this analysis following intensive data extraction, restructuring, and augmentation of specific data fields (including place of birth, place of residence, and role types) in consultation with subject matter experts from fields including the visual arts, performance, cultural policy, and architecture.

The datasets are available for use in computational analysis by arts and humanities researchers, creative industry experts, cultural theorists and others working on quantitative and qualitative investigations into gender, artistic networks, and socio-economic questions relating to the arts.

Health & Medicine

Sisters are doing it for themselves

We are continuing to add data from alternative sources to those we already have to enrich our understanding of historical and contemporary trends in arts employment, including from IMDb and the Australian and New Zealand Art Sales Digest.

By injecting new types of data and formats into a growing need to understand the relationship between gender and artistic incomes and participation, the ACD-Engine aims to help progress an important national conversation about the patterns of work across the cultural and creative sector and the future of the arts in Australia.

This research is funded by the Australian Research Council (ARC). The ACD-Engine is based at the University of Melbourne, with collaborators at the University of Queensland, the University of New South Wales, Swinburne University, Curtin University, RMIT, the University of Newcastle, Flinders University and King’s College London.