Getting to the source

Technology is empowering women experiencing domestic violence – now it could be extended to make men who use violence confront their behaviour.

Published 17 March 2016

Imagine a man with a history of abuse against his partner is about to threaten her. His heart rate goes up, he starts to pace and shout. Suddenly his smart watch buzzes a warning and a message pops on the screen.

“Need time out? Maybe a walk will help clear your thoughts. Let’s go,” it says.

For some men, it might be all he needs to rethink his behaviour and take some time out. The watch will even prompt him with questions designed to encourage him to self reflect and seek the help of services, which over time could help to end the abuse altogether.

Far fetched? Not at all. University of Melbourne researchers are working on just such an intervention that would use an online tool and smart phone application named PEARL. It would aim to encourage men who use violence and abuse to confront their behaviour, recognise it for what it is, and assist them to seek help to end it.

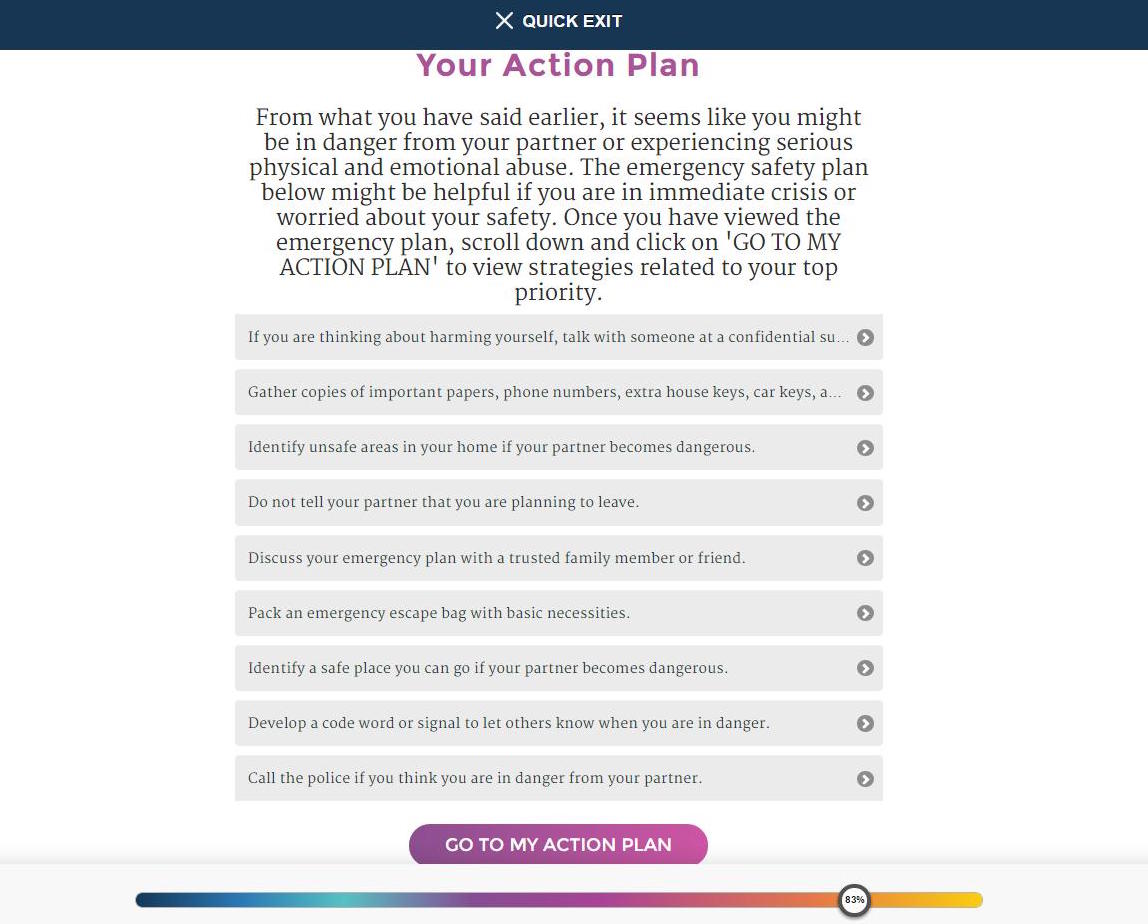

PEARL takes the same approach as the University’s Department of General Practice’s ground-breaking online and smart phone tool I-DECIDE, which is designed to help women self-inform and self-reflect in order to to confront the reality that they are in an abusive relationship. The tool, which has been in the testing phase for just over 12 months as part of an Australian Research Council funded Discovery Project, empowers women to do something towards their and their children’s safety and well being using techniques successfully used in face-to-face interviewing such as motivational interviewing and non-directive problem solving. But PEARL seeks to tackle the problem at the source – the man who is abusing.

Part of the solution

“For women, it is their reaction that needs changing to encourage them to name the behaviours as abusive and assist them to take actions on a pathway to safety,” says Professor Kelsey Hegarty, a domestic violence expert and general practitioner at the Department of General Practice, who is leading the development of I-DECIDE and PEARL. “But the behaviour itself is coming from men so we need to try using the same tried and tested techniques that work for diabetes or smoking to tackle what is a chronic social problem.”

Professor Hegarty stresses that using interviewing techniques and extending them to the online space of itself isn’t a silver bullet for addressing domestic and sexual violence. And nor will it help all abusers to stop, such as those unwilling or unable to honestly confront their behaviours. But she says the success of face-to-face counselling and encouraging signs that similar online tools are working for women, means it’s something we need to try as an early intervention.

“We need a whole of community-based approach to tackling domestic abuse and this is just one small part of the solution,” says Professor Hegarty.

She says interviewing aimed at encouraging men to self-reflect and change their behaviour “clearly may not stop men who use severe violence or hold gender attitudes supportive of violence against women. But it could be an effective tool for men who may just need to be jolted out of a pattern of behaviour, who are ready for change.”

“It is probably for the group of men where abuse has just started and is becoming a pattern that they can’t easily stop,” she says.

According to the World Health Organisation, one-in-three women worldwide, and 1.5 million women in Australia, report physical or sexual abuse by a male partner.

Professor Hegarty and a team of researchers from the University of Melbourne, Johns Hopkins University in the US, University of College London, Deakin University, and La Trobe University, have developed I-DECIDE that uses prompts and questions to encourage women to recognise they are in an abusive relationship and help them to take action. It has been inspired by similar online tools in the US, New Zealand and Canada. But I-DECIDE takes it further by including face-to-face techniques such as motivational interviewing and non-directive problem solving. In the process it encourages women to confront their priorities and make a decision.

Priorities and action

Such face-to-face techniques have been shown to be effective by a previous research project led by Professor Hegarty that found a brief course of one-to-six face-to-face counselling sessions with a doctor appeared to alleviate depression among women suffering domestic violence.

Funded by the Australian Research Council, the I-DECIDE project has recruited 427 women as participants, all of whom have expressed concern about their relationships. They have been split into two groups. The first are exposed to a version of I-DECIDE that like many online tools is limited to largely providing information. The second group is exposed to the full online version including the interactive modules that tailor an action plan to their level of abuse and danger and their own individual priorities for their relationship.

The idea is to compare the two groups to see if there is a difference in the level of self-reported feelings of depression and empowerment. The project has been going for just over a year and the researchers are in the process of analysing the results, but the qualitative comments they have received from participants are encouraging.

“My experience of being in I-DECIDE has given me the knowledge to realise that this isn’t my fault and that I am strong enough to walk away and decide on a better future for me and my children,” wrote one participant.

“This has been good for me to let you know how I feel. I don’t like talking to others as you don’t understand unless you have been through the whole domestic violence thing. I know I’m not being judged,” wrote another.

Together both comments highlight the big challenge in encouraging women to name what is happening to them. Too often women simply don’t recognise abuse for what it is and instead feel it is their fault. It means that too many women aren’t coming forward and seeking help from front line services like health practitioners, the police and specialised domestic violence services.

Automating interview techniques

“For many women it is hard to recognise domestic violence for what it is when they are in an environment of emotional abuse, with isolation and fear, as well as physical abuse that may be intermittent and include sometimes sexual abuse, which is the big hidden area,” says Professor Hegarty.

Non-directional interviewing involves avoiding leading questions and is deliberately non judgemental. Motivational interviewing poses questions that investigate people’s motivations and priorities to help understand their goals and how to get there. In I-DECIDE participants have to ask themselves what they like about their partner and what they don’t like. And they are asked what is most important to them or what they are most worried about, such as their children, finances or their own safety.

The automatically generated feedback provides people with a ‘mirror’ or reflection of what they really care about, and the severity of the threat posed by their partner. Based on this it recommends an action plan with clear self help strategies, such as what services are available to call.

For example, Professor Hegarty notes that in many instances women in face-to-face interviews will say that the positive side of their relationship is that at least their children have a father. But then when they are confronted by an extensive list of the negatives it jolts them into taking action for themselves.

While priority setting may seem obvious as a way to solving problems, women in abusive relationships are often so traumatised that their problem solving skills are impaired. As Professor Hegarty says: “Imagine if you have been told you are worthless for 20 years and you are anxious and fearful all the time – your problem solving ability is going to be reduced.”

While online interviewing isn’t a substitute for face-to-face interviewing, it’s big advantage is that it can bring in women who for whatever reason are reluctant or unable to seek out services. For these women the anonymity of an online tool can be useful. Similarly, an online approach is also expected to appeal to men who may be reluctant to admit to someone that they are perpetrating abuse.

Co-researcher Dr Laura Tarzia, deputy leader of the Researching Abuse and Violence program at the University of Melbourne, said that the message from focus groups of men who are abusive was that they were reluctant to engage health services but were attracted to the idea of online support. “The feedback was that an online process would allow them to ask a question without feeling that anyone was judging them,” Dr Tarzia says. “It was similar to what the women were saying – that they see technology as a non-judgemental and anonymous space.”

Behaviour interrupting technology

The researchers are developing PEARL in partnership with Tigerspike, No to Violence and Nexus Health. They have already developed a PEARL prototype aimed at early intervention. For a proposed trial they plan to engage general practitioners, counsellors, sporting clubs and online sites to recruit men using abuse in their relationships.

Going beyond that and actually developing technology that could interrupt abusive or violent behaviour would be a big step, but initial consultation with technologists at the University of Melbourne suggests it is readily possible. For example computer engineers are confident that by comparing patterns such monitoring technology will be able to distinguish between anger and joy when monitoring things like pulse rates and shouting.

“The computer and information systems people really think they can develop something that would interrupt people when their voice was raised or their pulse was going up, or they were walking around quickly. So it is doable from a technology view point,” says Professor Kelsey.

The challenge now is to complete the research and trials that could show that such interventions as I-DECIDE and PEARL actually work and then secure funding to put them into practice. For I-DECIDE that point has almost been reached.

Banner Image: Amy Dianna/Flickr. White Ribbon is Australia’s campaign to prevent men’s violence against women.