Helping corals survive a rapidly changing world

Professor Madeleine van Oppen wants to manipulate the complex relationship between corals and microbes to accelerate coral evolution

Published 13 October 2015

We live in a microbial world, even us humans. We have more microbial cells in and on our bodies than we have human cells, and even a large part of our DNA is derived from microbes – viruses and bacteria and so on. And that is true for all organisms. We now realise how important microbes are for our health and functioning.

I was trained as a marine ecologist and during one of my master’s research projects I got exposed to genetics. It was around the time that PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) methods were developed, which really was a huge advance in genetics because we could quickly pull out parts of the genome and sequence them. This technological development allowed a range of interesting ecological questions to be addressed. Then I did a PhD, using genetic tools to study the evolutionary history and population genetics of cold-water seaweeds. In 1997 I came to Australia to work on corals.

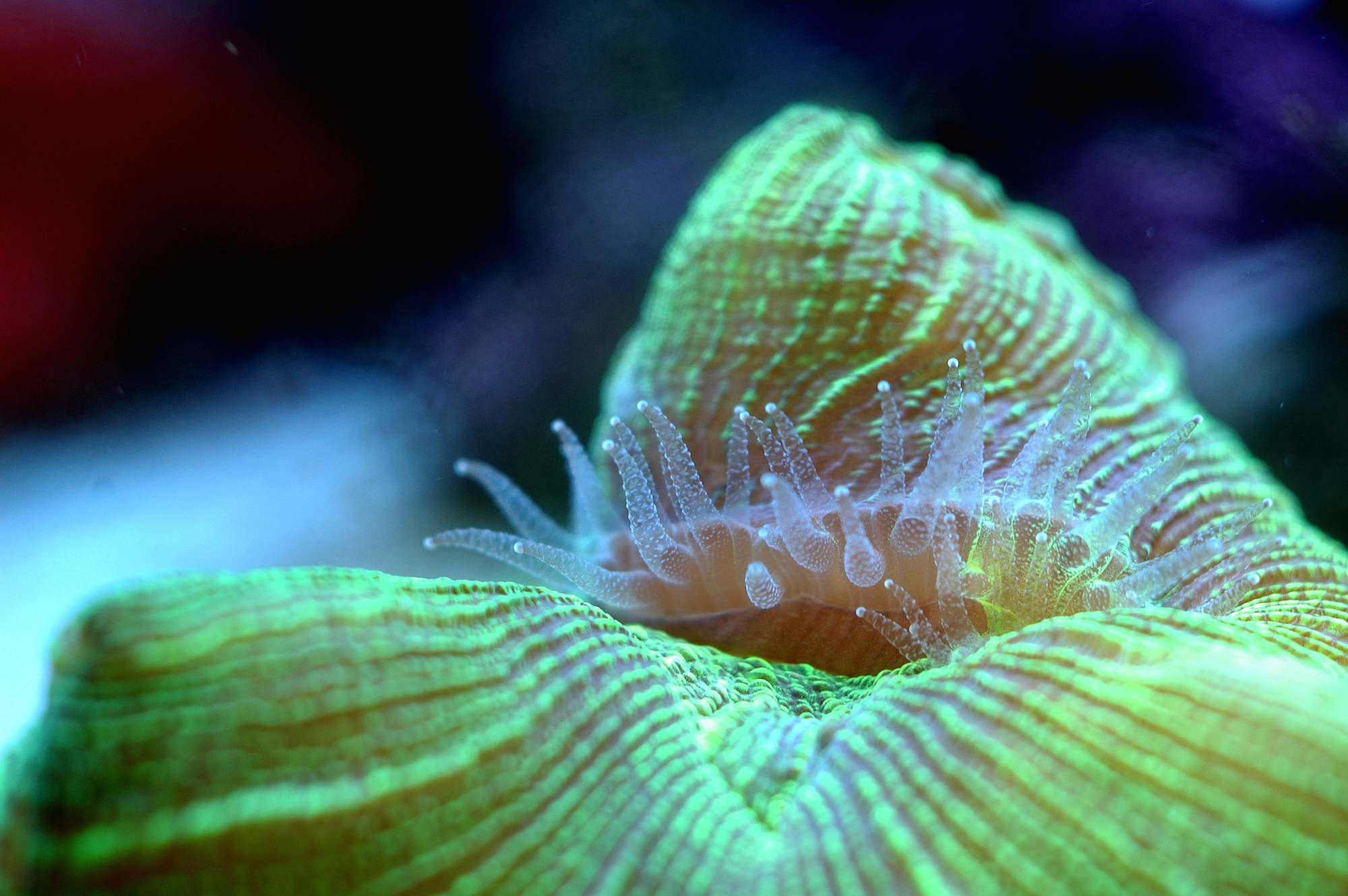

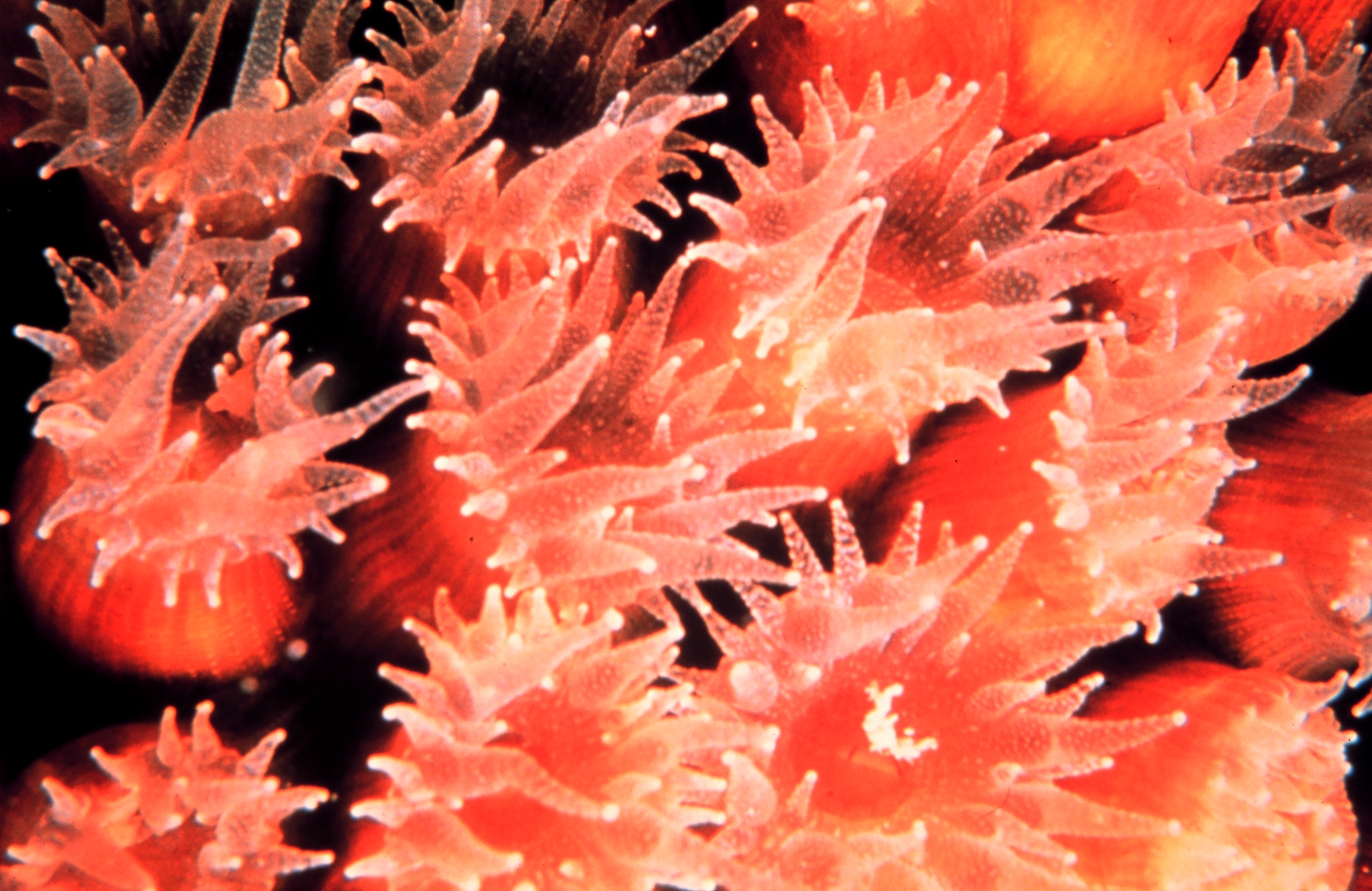

Corals have quite complex microbial relationships, or symbioses, because in addition to bacteria, they also live with single-celled plants, or algae. That plant lives inside the coral’s cells, and it uses the sun to make sugars. It leaks a lot of those sugars to the coral tissues and the coral relies on those sugars for nutrition.

Some corals derive more than 90 percent of their nutrition from this algal photosynthesis.

If the coral loses the symbiotic algae it will eventually die because it starves. During climate change driven extreme warm weather events – and also a range of other environmental disturbances – the symbiosis between the algae and the coral breaks down, so the coral basically loses those symbionts and it dies.

Corals have many mechanisms by which they can potentially adapt or acclimatise - they are very plastic organisms. The problem with climate change is the rate of change, so there’s concern that corals may not be able to respond quickly enough and we have already seen loss of coral across the world. And it’s predicted that will continue into the future.

We have just started a project where we are attempting to accelerate the rate of evolution in corals by manipulating them and trying to accelerate naturally occurring evolutionary processes in the hope that we can create some varieties that are more resilient to predicted future environmental conditions.

We call it ‘Assisted Evolution of Coral’. We will trial a range of different approaches. One is selective breeding of the coral animal itself. We are also trying to evolve the algal symbionts in the laboratory and make them more heat and acidification resistant and then put them back into the coral animal and examine whether that creates a more resilient organism. We are examining whether non-genetic factors – epigenetics – play an important role in acclimation of corals across generations. For example, if we pre-condition an adult coral to warmer conditions, will its offspring be more tolerant to warmer water?

And finally, can we actually change the composition of the microbial symbionts of corals, and may that be a way by which we can enhance their resilience?

In the next five years we will figure out which of these approaches will work for coral – and hopefully some of them will – and then the aim is to move into a second phase where we can hopefully implement some of these approaches in coral reefs, pending regulatory approvals.

I’m really keen on this assisted evolution project because it potentially has an impact on our environment. It’s a major undertaking and it builds on decades of research into understanding mechanisms of adaptation and acclimatisation in corals. We can actually do something, something that is beneficial to our environment and in that way to society as well.

– As told to Dr Daryl Holland

Banner image: Brain coral, Trachyphyllia geoffroyi (Public Domain)