Arts & Culture

How a quest for the past found a living present

Australia’s under appreciated colonial art is a window to the past that can help us understand the fraught and violent history of settlement

Published 21 December 2018

“When I point it out you won’t ever be able to look at this painting again without noticing it.”

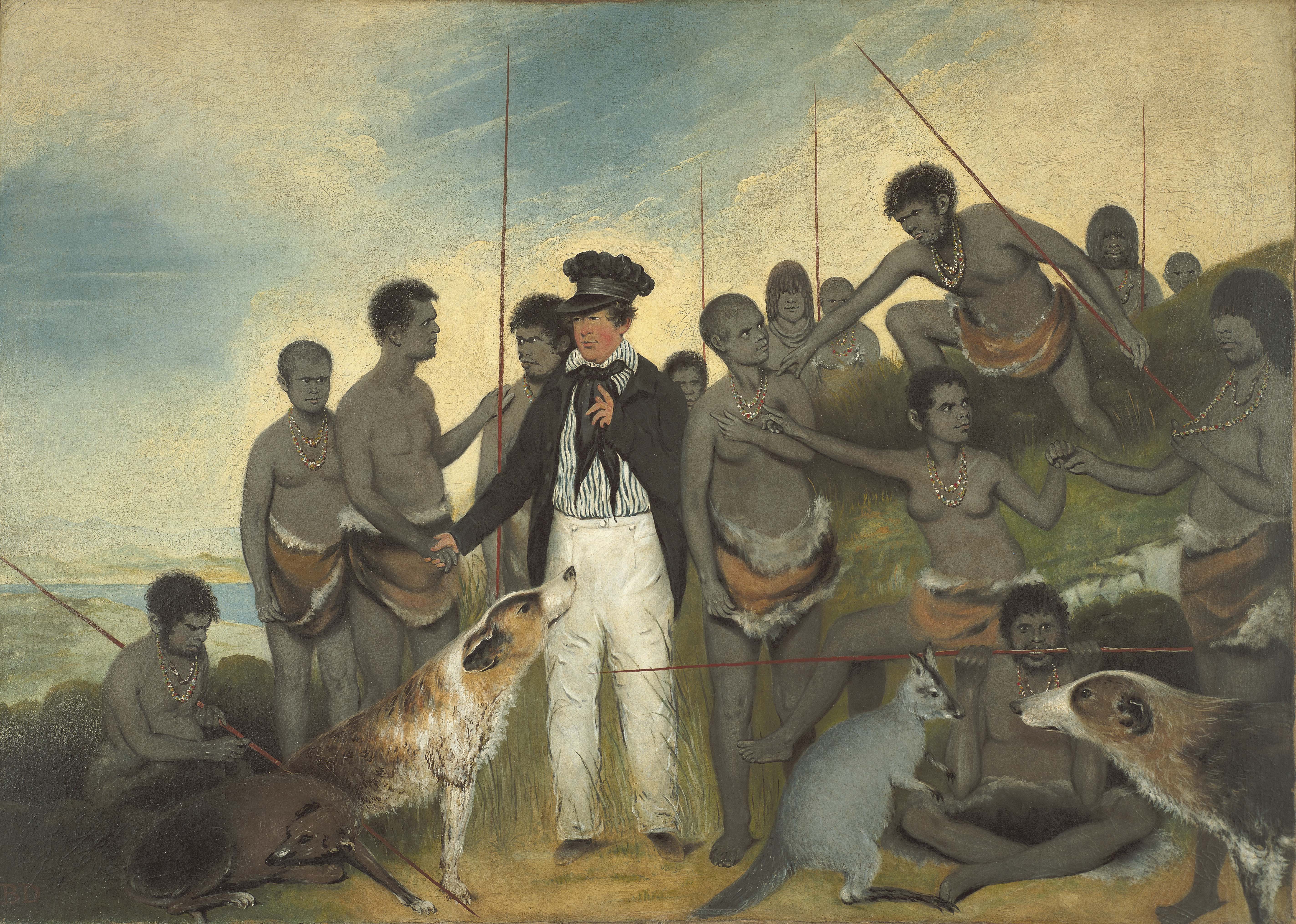

Historian, curator and artist Dr Greg Lehman is talking to me in his office at the University of Melbourne, pointing at a big poster on his wall of Benjamin Duterrau’s 1840 painting ‘The Conciliation’.

I look hard at the painting.

At the centre stands Augustus Robinson, the Englishman credited with ending Tasmania’s murderous Black War – fought between the mid-1820s and 1832.

The painting depicts him persuading the last surviving Aboriginal resistance fighters to surrender. On the surface it seems a grandiose and perhaps even pedestrian piece of hero worship that a contemporary viewer might quickly dismiss.

But there is something much deeper going on.

Arts & Culture

How a quest for the past found a living present

Dr Lehman points out that of the 14 Aboriginal figures in the painting, only one isn’t wearing a traditional necklace, and that’s the man shaking Robinson’s hand as leader of the group. Off to the far right another Indigenous man is holding out his necklace as if to remind his leader of what is at stake.

“It isn’t a coincidence,” says Dr Lehman. “I think Duterrau is using the necklaces as a symbol of Aboriginal culture and sovereignty, and the man holding out the necklace is reminding us of what is at stake.

“At this point the war had already decimated the Aboriginal population in Tasmania from perhaps 6,000 to just a few hundred in the space of about 20 years, and now here is a massively significant transaction taking place – they are surrendering and accepting Robinson’s assurances.”

These assurances would prove to be empty promises. The Indigenous band was exiled to the remote Flinders Island in Bass Strait. “They were effectively put into permanent offshore detention,” says Dr Lehman, deliberately referencing Australia’s current treatment of refugees.

“What appears to be, at first look, a conventional historical painting of the time, depicting a formative event in the colony, is in fact a scene of betrayal.”

Dr Lehman is quick to admit that his interest in the painting borders an obsession, but it’s only part of his broader resolve to revive interest in Australia’s colonial art because, just like ‘The Conciliation’, it has a lot to tell us.

Australia, he says, has long ignored its fraught history of colonial settlement, preferring to put the violence of the frontier wars behind what he calls “a firewall”. The challenge in properly understanding colonial art, says Dr Lehman, is that we have lost the visual literacy to accurately look at and comprehend these pictures.

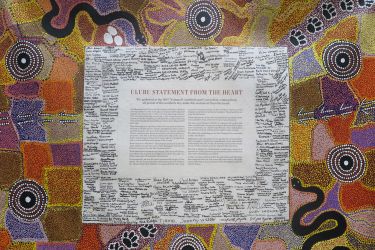

“If people can become a little bit more familiar with these art works and are informed by them, my hope is that it will help people to see through this colonial firewall we’ve erected around us,” he says.

A key element of that effort has been working with environmental lawyer and cultural historian Tim Bonyhady to co-curate a major travelling exhibition The National Picture: The Art of Tasmania’s Black War. The exhibition ran at the National Gallery in Canberra earlier this year and is now at the Queens Victoria Museum and Art Gallery in Launceston, Tasmania.

‘The Conciliation’ is the centrepiece of the exhibition, but the collection is actually named after a much larger work by Duterrau, ‘The National Picture’, that focused on the same themes. But this painting has been mysteriously lost for more than 160 years – the last record of its whereabouts dates to 1851, the year of Duterrau’s death.

Politics & Society

Duty and honour at the heart of Indigenous recognition

“The fact that it’s missing isn’t so much ironic, as apt,” says Dr Lehman. “It’s a metaphor for what has been missing from the Australian consciousness.

“What we are looking to generate with exhibitions like this, is an irresistible tide of visual literacy that can help sweep Australia forward in terms of this country’s ability to look at its past with eyes wide open – rather than shielded from the uncomfortable glare of the injustice and terror inflicted on Aboriginal Australians, that still today stops many people from looking back.”

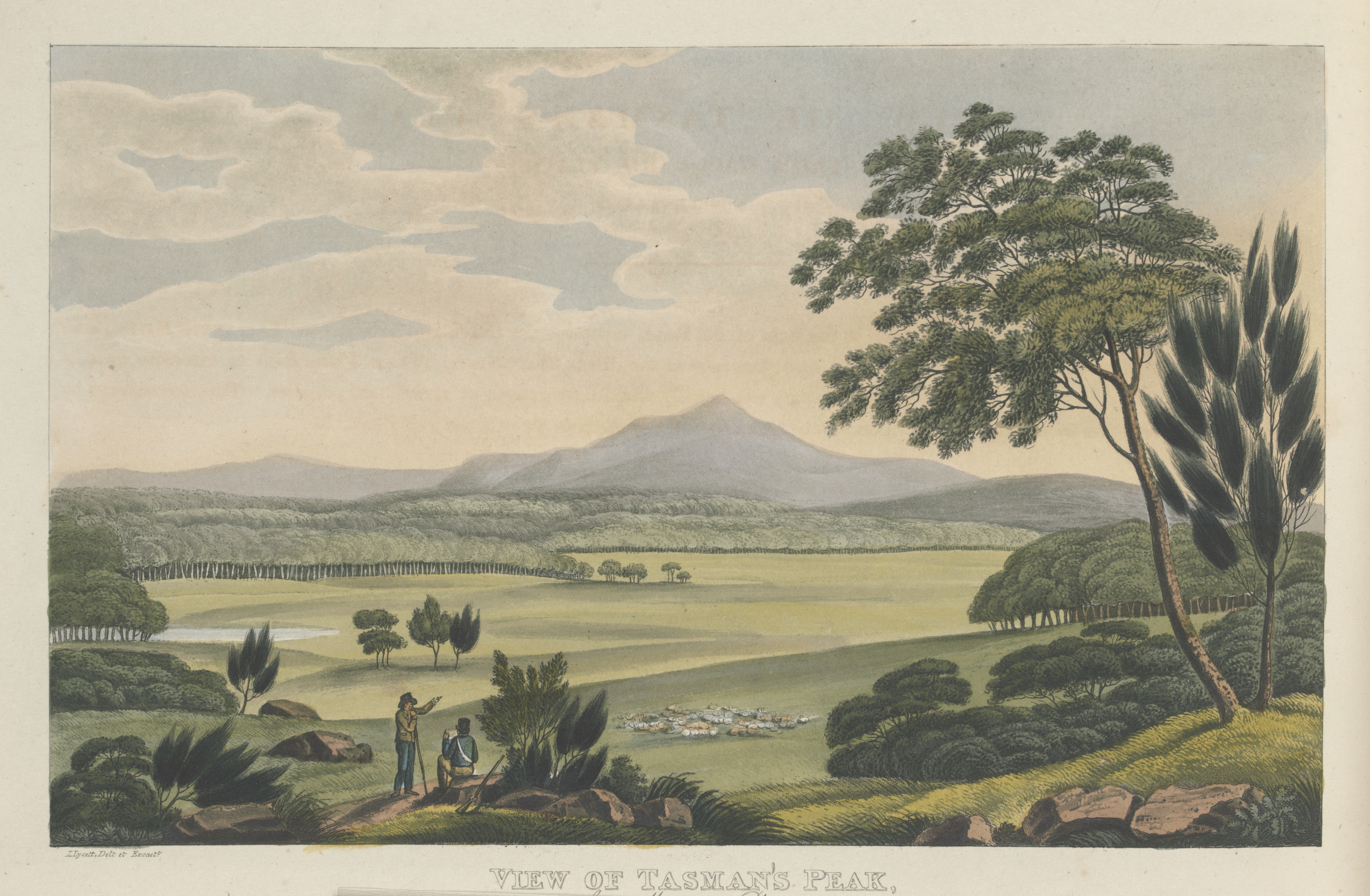

Indeed, at the height of the Black War, Dr Lehman points out that colonial artists conspired in the collective refusal to “look” and see the war for what it was by simply leaving Indigenous Australians out of any scenes that depicted Tasmania.

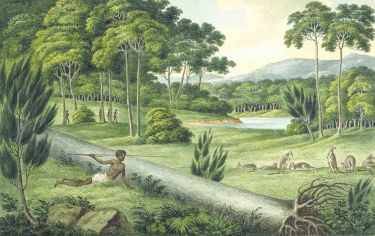

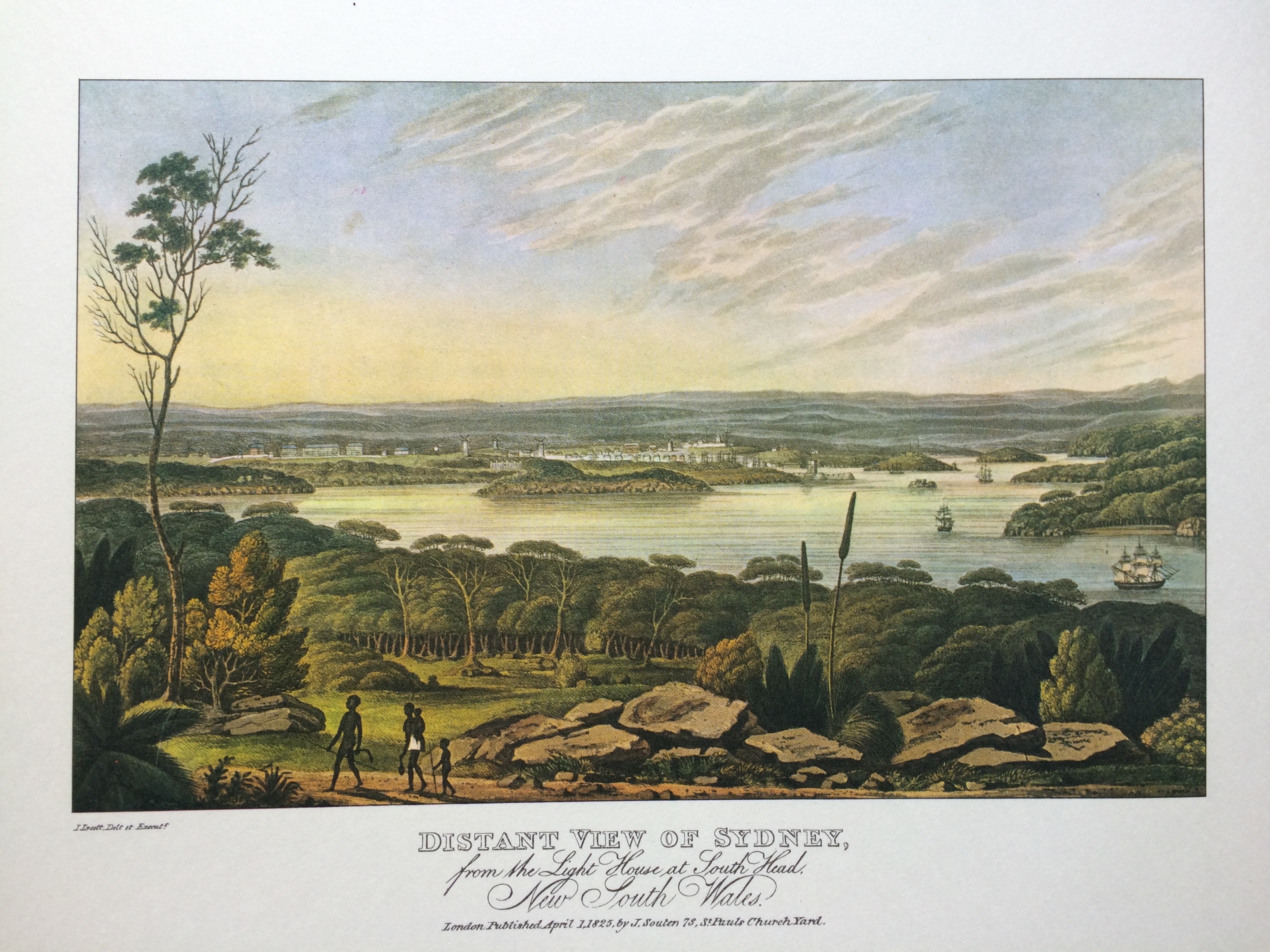

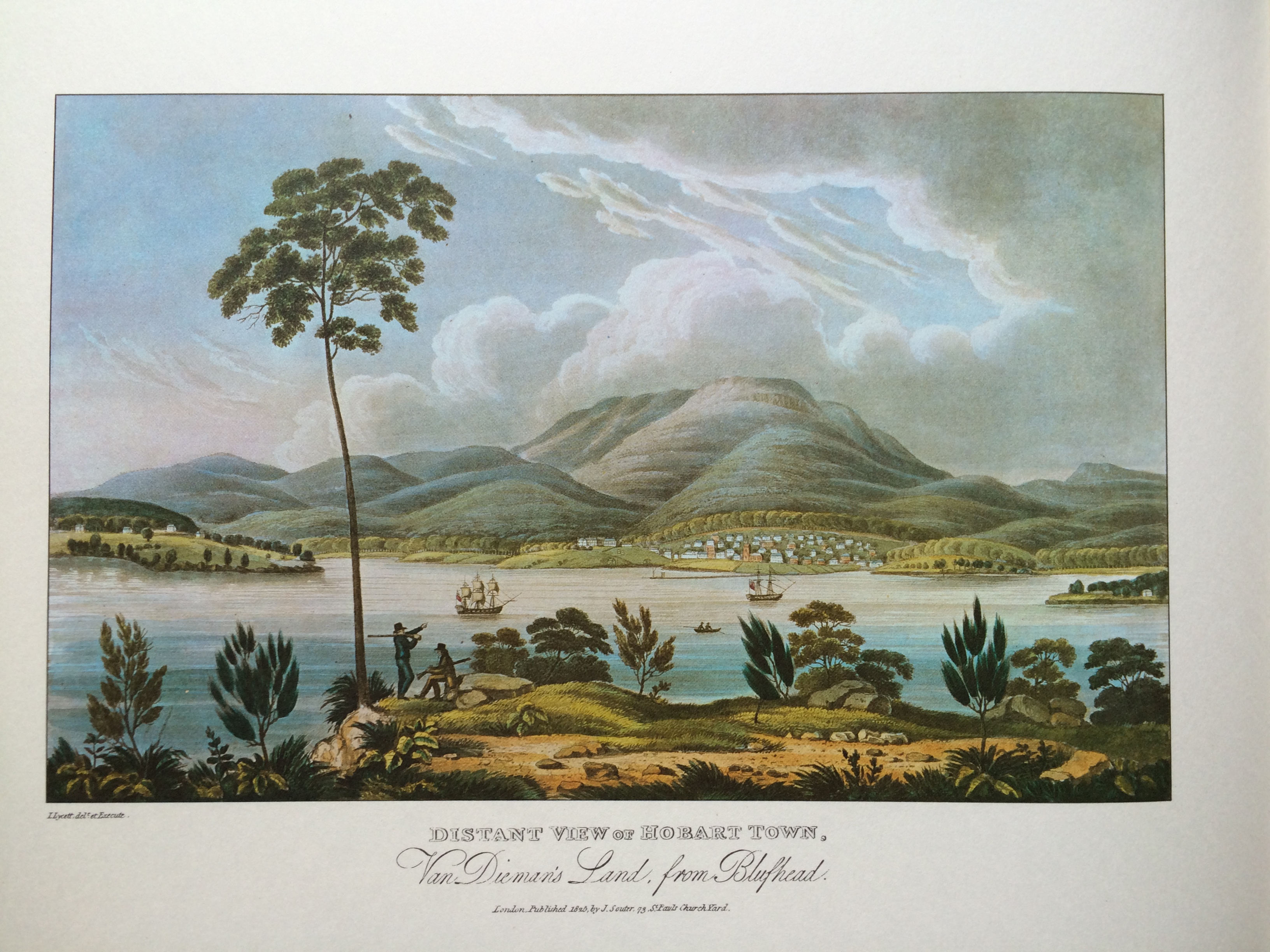

But in landscape paintings of the colony in New South Wales, the very same painters were regularly including and referencing Aboriginals.

“If there were just one or two examples of this happening then it wouldn’t amount to much, but every single one of these artists who are producing views of NSW include Aboriginal people.

“But when they come to producing Tasmanian views, none of them have Aboriginal people in them.”

Dr Lehman argues that in NSW the Aboriginal population had been subdued by Governor Macquarie’s military expeditions and the resultant massacres. At the same time, the conflict in Tasmania continued to rage and the authorities didn’t want the fighting broadcast too widely.

“I think the war was the reason they didn’t want to acknowledge that Aboriginal people were even in Tasmania.”

Dr Lehman’s passion for colonial art began when he came across the genre as an historian who had previously purely focused on text-based history.

“My intuition told me there was a lot to this art work and it just wasn’t good enough to simply reproduce these images as an accessory to written history. These works have a lot to say.”

Arts & Culture

Aboriginal voices in the afterlife of photographs

Making colonial art more accessible as a way to help Australians understand and reconcile their history is a personal goal for Dr Lehman, who can trace his ancestry back to the Trawulwuy people of north eastern Tasmania.

“People often say to me, ‘Greg, what are you? One-thirtieth Aboriginal? How can that be important to you when you look more European than anything else?’

“And I tell them that I’m happy to acknowledge my German, Irish and English backgrounds, but what is unique about my Tasmanian heritage is that once you go back beyond the marriages with settlers, I have a family that has uninterrupted continuity with a population that was living for thousands of years in almost complete isolation on this island.

“That is one way of understanding why Aboriginal identity is so important for people and why it matters.

“For me, it means I can bring a particular perspective to my work that adds some immediacy and poignancy to this story.”

As a University of Melbourne McKenzie Postdoctoral Fellow, Dr Lehman is extending into the 20th Century his research into the role of visual representation, including photography, in understanding Australia’s relationship with its Indigenous history.

Banner image: Courtesy of Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery