Arts & Culture

Confronting the feel, smell and taste of blood

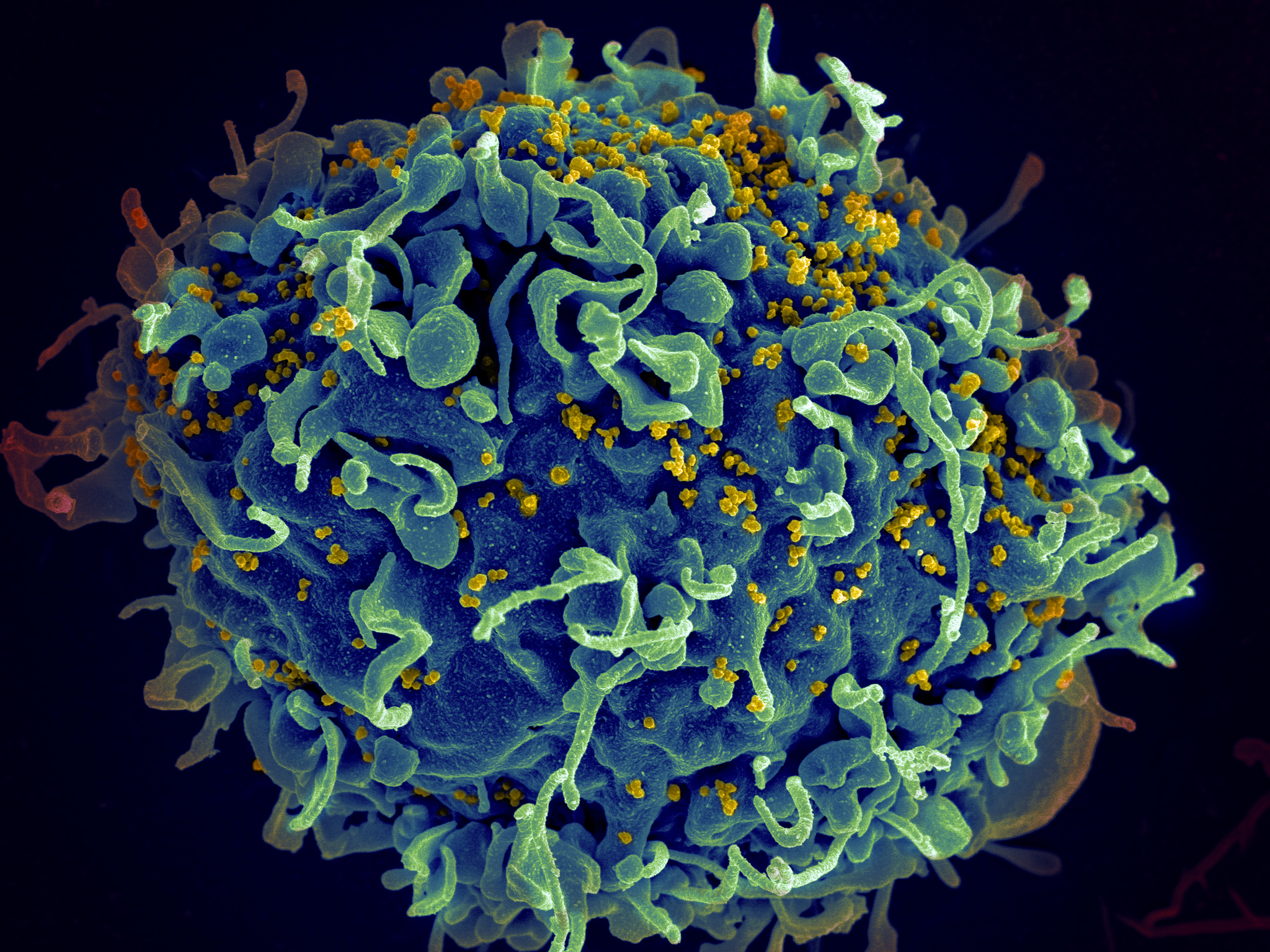

Clinical trial suggests HIV can’t replicate in people on antiretrovirals in what is a key finding for efforts to develop a cure

Published 5 March 2018

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) has dramatically changed the outlook for people living with HIV, so much so that people living with the virus can now enjoy a near normal life expectancy. In addition, ART eliminates the sexual transmission of HIV.

However, ART is not a cure and treatment is required lifelong. Although treatment is much simpler now than previously, often requiring just a single tablet a day, it is expensive, comes with side effects, and drug resistance is beginning to emerge globally.

That is why we need to find a cure for HIV or find a way for people living with HIV to stop treatment and keep the virus at low levels.

The barrier to curing HIV is complex. HIV can persist in a long-lived sleeping form, called latency. In HIV latency, the virus is able to become part of a person’s DNA and effectively hide from both the immune system and antiviral drugs.

What has been more controversial is whether in addition to latency, the virus also continues to replicate at very low levels on ART, possibly in tissue sites like the lymph tissue or gastrointestinal tract.

But we have now shown that HIV is highly unlikely to be replicating on ART, which is a significant finding for ongoing research into a potential cure.

HIV attacks the immune system and remains a major public health problem. Across the world in 2016 about 1 million people died from HIV-related causes and there are about 37.7 million people living with HIV.

Arts & Culture

Confronting the feel, smell and taste of blood

To address the question of whether the virus is still replicating on ART, I led a team of Melbourne- based researchers from the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity – a joint venture of the University of Melbourne and Royal Melbourne Hospital – to carry out a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial.

In collaboration with the Alfred Hospital and Melbourne Sexual Health Centre, we enrolled 40 people living with HIV who were taking suppressive ART. This meant that virus couldn’t be detected in blood of the participants using any standard laboratory test.

We randomly selected half the group to receive an additional antiretroviral called dolutegravir and the other half a sugar tablet placebo for an eight-week period.

We performed frequent measurements of both the virus and the immune system using very sensitive laboratory techniques to measure different forms of the virus.

We found no changes in any markers of the virus or in the immune system among those taking the extra drug, nor were there any changes in a four-week follow up period (results presented at the annual Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Boston).

Dolutegravir is a member of a family of HIV drugs called integrase inhibitors. These drugs block the virus from entering into the host DNA, a process known as integration.

If there was ongoing virus replication in someone on ART, then dolutegravir would signal it by effectively shutting the door on the virus, causing it to start to build up inside the cell on the outside of the cell nucleus, the engine room of a person’s DNA. But when we looked specifically for this special form of the virus that sits outside the nucleus, there was no evidence that this happened.

We also looked for downstream effects of any virus that might be lurking around and tickling the immune system. When we looked at markers of an activated, or alerted, immune system, again these didn’t change.

In other words, there was no sign the virus was replicating. We know that participants were definitely taking dolutegravir as we could clearly measure the drug in their blood.

This is not the first trial to look at adding additional antiretrovirals to see if the virus is replicating in people on ART. There have been many previous studies, including studies of integrase inhibitors, other than dolutegravir.

However, many of these previous studies were done several years ago when ART was less potent. In addition, these previous studies didn’t perform very frequent measurements of the virus as was done in this study.

It is important to note that only blood was analysed in this study and not tissue, meaning that it is possible that there is some virus replication happening in tissue, but we think this is unlikely.

Together this trial demonstrates that residual virus replication is very unlikely to be occurring on ART. This is an important firstly because it confirms that ART alone, no matter how potent, won’t eliminate or cure HIV.

Second, it is important for designing future cure strategies. One potential strategy our group and other researchers are looking at is to ‘wake up’ the virus so that infected cells become visible to the immune system.

But if that is to safely work we need to first be sure that the virus won’t replicate as soon as it ‘wakes.’ We are now a significant step closer to being sure this won’t happen.

Banner image: Getty Images