Arts & Culture

Zanuckville: Australia’s strangest suburb?

A new book explores the more-or-less forgotten crime novels of one of Australia’s most successful authors, George Johnston

Published 27 October 2023

George Johnston is one of the most successful Australian novelists. Many Australians will have read his most famous books – My Brother Jack (1964) and Clean Straw For Nothing (1969); both of these autobiographical novels won Miles Franklin Awards.

While he may be most famous for writing My Brother Jack – arguably the great twentieth-century Australian novel – Johnston wrote many books throughout his career.

These include five crime novels – Twelve Girls in the Garden (1957), The Saracen Shadow (1957), The Man Made of Tin (1958), The Myth is Murder (1959), and A Wake for Mourning (1962) – featuring the quixotic American archaeologist and amateur sleuth, Professor Ronald Challis.

But Johnston wrote these books under the nom de plume Shane Martin.

George Johnston had married his second wife, the Australian writer Charmian Clift in 1947 and his pseudonym was made up of the names of their daughter, Shane, and son, Martin. The couple’s third child, Jason, was born in 1956.

Arts & Culture

Zanuckville: Australia’s strangest suburb?

Johnston wrote the first four Challis novels on the island of Hydra in Greece, where the family lived between 1955 and 1964. The fifth Challis novel was written in Stanton, England, where they lived for six months in 1960-61.

Like everything that Johnston wrote before My Brother Jack, the Challis novels are out of print and more-or-less forgotten.

Fortunately, I found second-hand copies of them in the lead-up to an exhibition I curated in 2008 called Murderous Melbourne, which focused on three Melbourne authors from the ‘Golden Age’ of crime fiction writing – Arthur Upfield, Sidney H. Courtier and June Wright.

These days, copies of Johnston’s crime books are very hard to find and often expensive. But reading these books made me wonder about their obscurity.

More than a decade on from getting copies of these “pot-boilers”, I’ve written a book which aims to recover and restore Johnston’s much-maligned Challis novels from limbo.

As rare book specialists Des Cowley and Susan Millard say in their preface:

“The ‘Shane Martin’ books were not published in Australia, and few copies appear to have entered the country at their time of publication. The State Library of Victoria, based in Melbourne – the city of Johnston’s birth – holds all five titles, though, at the present time, they are catalogued under ‘Shane Martin’ and the records make no link whatsoever to Johnston.

Arts & Culture

Rescuing Australia’s lost literary treasures

“The Baillieu Library, at the University of Melbourne, despite housing an extensive collection of Australian literature, to date holds none.

“Johnston’s ‘Shane Martin’ novels rarely surface in the antiquarian book trade, and the few book dealers listing them appear entirely unaware of their link to a major Australian literary figure.”

George Johnston’s five Challis novels deserve much more attention than they have received because – besides being excellent thrillers of a much higher order than most critics have conceded – they reveal much about Johnston, one of Australia’s best-loved and most successful writers.

Since the novels are hard to come by, I’ve included in my book detailed summaries of the intricate storylines, followed by in-depth analyses of the events, people and places that influenced them.

Let me mention just a few of the things I’ve discovered.

Johnston visited, lived and worked in around 60 countries during his life and his 25 books were partly a record of his travels.

After leaving a London-based journalism job, Johnston went to live in Hydra for nine years with his wife.

In 1957’s Twelve Girls in the Garden, George Johnston drew heavily on his knowledge of art and art history that he learned while training to become a lithographer as a teenager.

But Johnston also drew on his personal relationships as well as his experiences.

One of the novel’s protagonists, the architecture student Branden Flett, lived in the Chelsea house of Johnston’s friend, the Australian artist Colin Colahan, and Professor Challis’s London landlord, Mr Valentine, was modelled on Johnston’s friend and colleague, the Australian journalist and author, Victor Valentine.

Memories of one of Johnston’s old Melbourne haunts, the Saracen’s Head Hotel in Bourke Street, inspired the title of his second Challis novel, The Saracen Shadow.

A two-week junket to the Dordogne River region of France in 1953, when George was the London correspondent of the Sydney Sun, became the setting of the same book.

In The Man Made of Tin, published in 1958, Johnston based the wrecking of the Danish freighter Thekla in a storm off the coast of Cornwall on the real-life wrecking of the German Cargo ship Traute Sarnow in a storm off the coast of Cornwall in 1954 – which he’d reported on for the Sun.

And, with no deception whatsoever, Johnston named Professor Challis’s Cornish landlord Sam Jackett after his friend and colleague, the Cornish journalist Sam Jackett.

Arts & Culture

Life on the edge of the Great Sandy Desert

There are several similarities between the fourth Challis novel, The Myth is Murder and The Maltese Falcon – both the 1930 detective novel by American writer Dashiell Hammett and the noir film, written and directed by John Huston in 1941. For example, Johnston modelled the creepy crook in The Myth is Murder, Johnny Franz on Peter Lorre’s portrayal of Joel Cairo in Huston’s film.

Also, George Johnston based the person everyone is chasing in The Myth is Murder, the controversial archaeologist Edmund Grosteller, on Professor Challenger, the adventurer in The Lost World (1912) by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Finally, A Wake for Mourning took Johnston back to where he started as a sixteen-year-old casual reporter with the Argus newspaper in Melbourne, writing about old sailing ships.

On the personal side, Johnston also used the absent villain in A Wake for Mourning to get back at his wife, Charmian Clift, for having affairs. Johnston named him after Patricia Simione, a woman with whom he had had an affair – perhaps reminding Clift that what was good for the goose was also good for the gander.

I suspect that, deep down, George Johnston liked to think of himself as Australia’s Ernest Hemingway.

So, imagine if Hemingway scholars chose to ignore five of the books he wrote, even though they were vehicles for trying out different things – some later used in his other books.

This ignores what Johnston revealed of his personal and professional contacts as well as his views on all sorts of things from food and wine to homosexuality – all because he wrote them using a pseudonym and once suggested they were lurid tales written to make some desperately needed money.

That would not be very scholarly, would it?

Well, that is what most Johnston scholars seem to have done. They have chosen to ignore Twelve Girls in the Garden, The Saracen Shadow, The Man Made of Tin, The Myth is Murder, and A Wake for Mourning because he once described them as “pot-boilers” and wrote them under the name Shane Martin.

But, hopefully, not anymore. At the very least, George Johnston’s five Professor Challis novels are worth a second thrilling look.

Dr Derham Groves’ new book Homicide On Hydra: George Johnston’s Crime Novels,published by Hog Press, is available online and in good book shops.

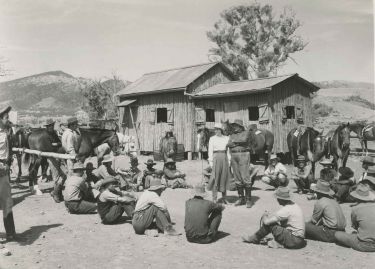

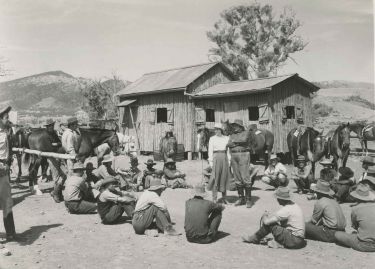

Banner: George Johnston and Charmian Clift in Hydra, Greece by James Burke/The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock