Health & Medicine

Is there a preferred COVID-19 vaccine for Pacific Island countries?

India’s second wave of COVID-19 is a humanitarian disaster but vaccines and tested measures, like limited lockdowns and social distancing, can turn the tide

Published 3 May 2021

The situation in India is dire.

I have critically ill friends and colleagues there and I dread every Whatsapp message that brings more news of more critically ill contacts … and worse.

Many in Australia will be receiving similar messages from friends and relatives in India, given the country’s large diaspora.

The number of COVID-19 cases a day have totally overwhelmed the health system in India, leading to a surge of the Case Fatality Rate (CFR). The actual number of infections is likely many times greater than what is being diagnosed. Yet the peak is still probably two weeks away, and it’s estimated we could be seeing around 13,000 deaths a day by then.

But there is hope.

I do not want to diminish the sheer scale of this humanitarian tragedy, but I write with some cause for hope in the midst of this darkness.

Health & Medicine

Is there a preferred COVID-19 vaccine for Pacific Island countries?

The international community is responding and within weeks masses of supplies will be entering the health system. Oxygen, raw vaccine materials, medications and ventilators are being flown in, including Australian-developed FREO2 devices that can produce medical-grade oxygen without the need for electricity.

Beyond responding to the acute humanitarian disaster in India, we need to flatten the infection curve there and prevent further cases.

Fortunately, the B.1.617 strain of SARS-CoV2 that is driving the surge in cases in India seems to not be deadlier, although it does seem more infectious. Before the health system was overwhelmed, the CFR for this second wave in India remained low – at just over one per cent.

The age of infection and death also seems to be similar to the first wave. India is a young country and the young rarely die from COVID-19.

Of course, the CFR shoots up as the health system is overwhelmed and care becomes inadequate, causing rare outcomes – like young people dying – to become common when there are hundreds of thousands of new infections a day.

This means we need to get back to the basics of what we know works.

India did the right thing to flatten the first wave at its peak. Between September and November 2020, without an arbitrary country wide lockdown, India was able to effectively control the virus with strict social distancing measures, time limited lockdowns and by quarantining hot spots.

Health & Medicine

Saving lives when the power goes out

And we know what not to do.

Out of necessity perhaps, India had gone back to business-as-normal with minimal adherence to the remaining restrictions, poor mask usage and mega-events ranging from protests, rallies, festivals and weddings. Such an environment was what allowed the original virus to spread like wildfire in Wuhan, China.

One hope is that herd immunity in India can’t be too far off and that’s the only real way out for India, but this can be achieved through either immunisation or infection.

Blood serum testing surveys and modelling have indicated infection rates ranging from 20 to 60 per cent, and some commentators suggested this would guard against a rapid second wave.

Either way, come June, we may well see a rapid downstroke in infections, just as steep as the upstroke.

Ideally, India can reach herd immunity as much by vaccination as by infection.

We need a rapid increase in immunisations, and India has the experience, the workforce and the technical capacity to do this – India’s Pulse Polio program launched in 1995 was a gold standard mass immunisation effort.

Furthermore, the AstraZeneca vaccine seems to be very effective at decreasing death, with evidence coming out that the vaccine seems to be working against the current infections with very low deaths/hospitalisations amongst the vaccinated.

Health & Medicine

What is Post-COVID-19 Neurological Syndrome?

And India has vaccinated many healthcare workers – with 20 million receiving at least one dose. At CMC Vellore, one of India’s biggest hospitals, about 9,000 staff have been fully immunised, and none have been hospitalised during the second wave. While some vaccinated staff contracted COVID, the disease was not severe.

While some still contracted the virus, none have been hospitalised yet.

International cooperation and assistance is important. We are all in this together and our world can only return to ‘normal’ when we all countries have COVID-19 under control.

We need to promote vaccines. There is much negative talk in the media about very rare side effects, but Astra Zeneca (and other vaccines) are highly effective at preventing hospitalisation and death from COVID-19. If we have another wave, we will want our health workers and populations to be protected.

Achieving herd immunity by rapid population infection is catastrophic. Even if tight control isn’t possible ongoing precautions – mask wearing, postponing large gatherings, social distancing and targeted shutdowns – are crucial.

I remain hopeful that by scaling up its response and vaccine program, working with foreign assistance, and capitalising on the country’s young demographics, India can turn around a devastating pandemic.

Charitable organisations working at the front line that University of Melbourne has partnered with and are open to receiving donations include:

CMC Vellore: upsizing to 1500 COVID-19 beds. They have written to us outlining their extensive needs including equipment, PPE and patient support.

Emmanuel Hospital Association: 20 charitable hospitals in rural India serving the poor. Requesting support to purchase PPE, medications, ICU equipment.

The Catholic Health Association of India: responding to COVID-19 across 3500 health facilities across in India. Through the Mary Glowrey Training Initiative, the University of Melbourne is helping increase CHAI’s capacity to respond to COVID-19.

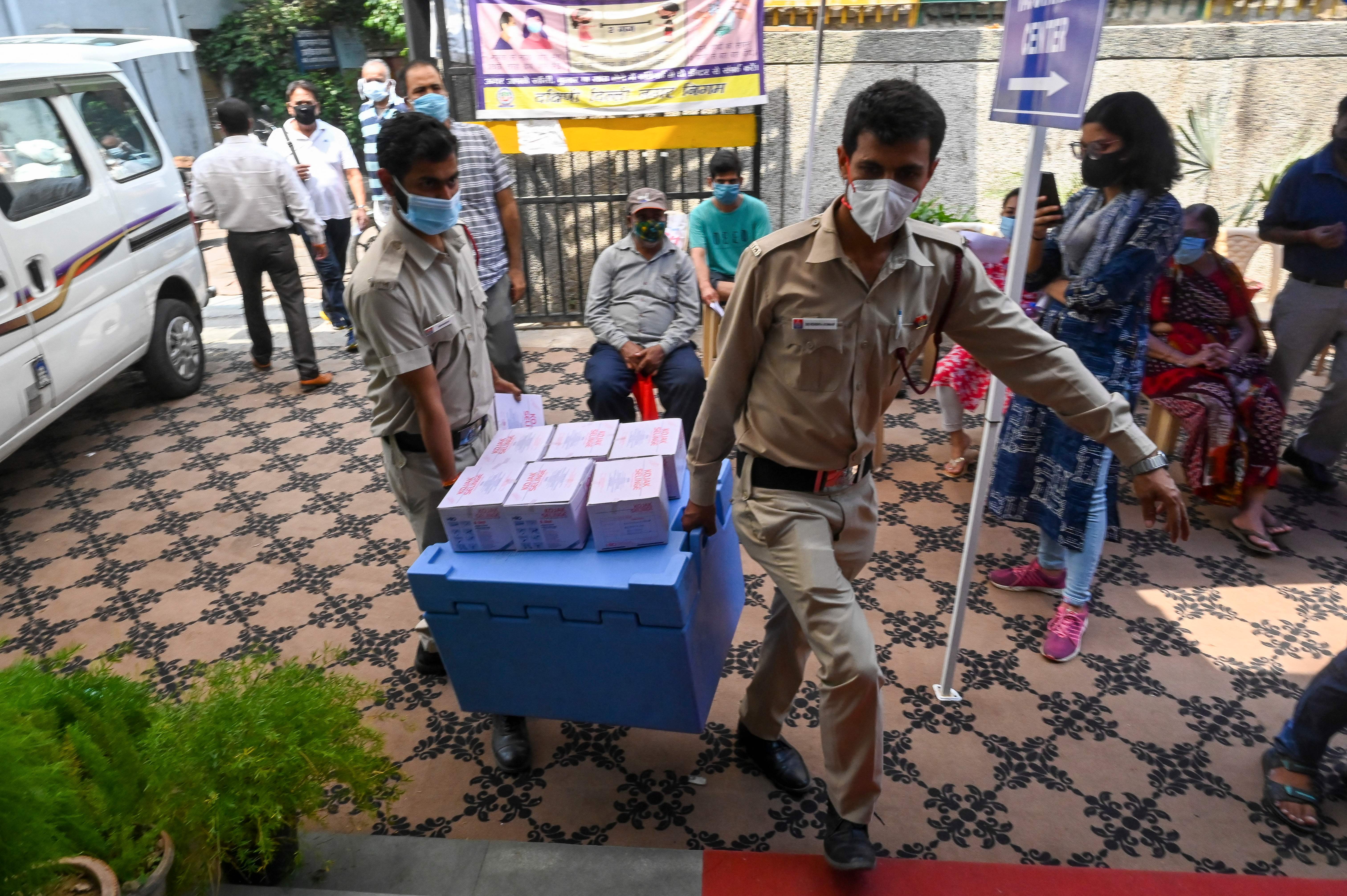

Banner: Vaccination centre in Mumbai, May 2021. Picture: Ashish Vaishnav/Getty Images