Arts & Culture

Restoring one of the world’s rarest maps

Images of a cockatoo in Frederick II of Sicily’s falconry book reveal how trade routes around Australia’s north were flourishing as far back as medieval times

Published 25 June 2018

Among the hand-written documents, books, and ancient artefacts in the Vatican Library is a 13th century manuscript on falconry written in Latin by or for the Holy Roman Emperor - King Frederick II of Sicily.

Frederick’s De Arte Venandi cum Avibus (The Art of Hunting with Birds) dates from between 1241 and 1248. In its margins are nine hundred drawings of falcons, falconers and other animals kept by the emperor at his palaces.

Four of these images depict a white cockatoo, described in the text as a crested, talking parrot - a gift from ‘the Sultan of Babylon’.

The discovery of these images, which are published in the journal Parergon, highlight the fact that during the medieval period, merchants plying the waters just to the north of Australia were part of a flourishing trade network that reached west to the Middle East and beyond.

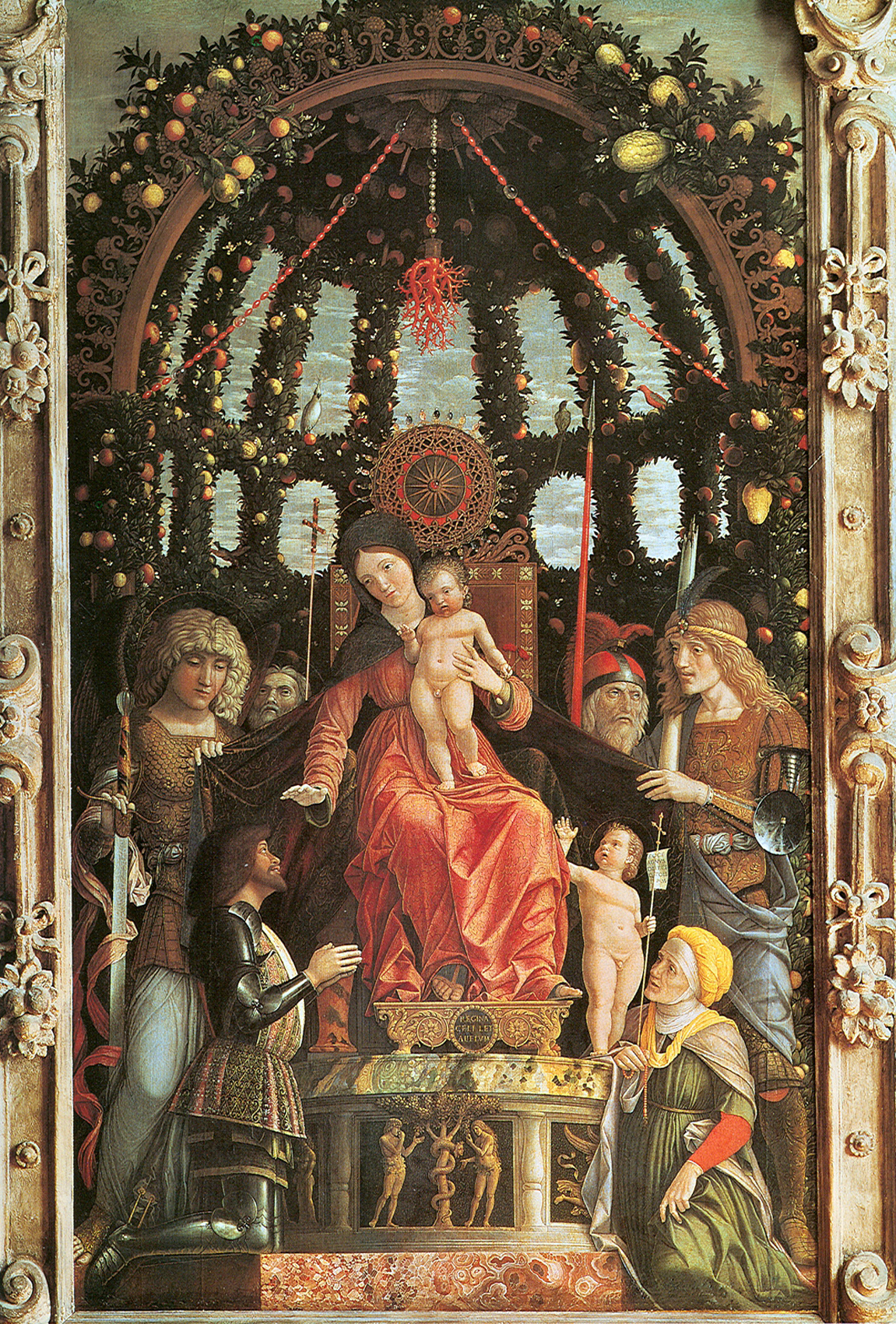

In 2014 I published an article on an Australasian cockatoo in an altarpiece painted in Italy in 1496 by Andrea Mantegna. As this Sulphur-crested Cockatoo or Yellow-crested Cockatoo (also known as a Lesser-crested Cockatoo) appeared to have been painted from a live model, which would have travelled to Mantua primarily overland, I saw this as evidence of the complexity and range of Southeast Asian trading networks prior to direct European contact.

I had thought Mantegna’s cockatoo was the earliest European image of a cockatoo until I was contacted by Pekka Niemelä, an emeritus professor of biodiversity and environmental science at the University of Turku in Finland, in February 2015. He and colleagues, Jukka Salo - a zoologist, and Simo Örmä - Intendant of the Finnish Institute in Rome, had been working on identifying the images of the cockatoo in Frederick’s manuscript.

I was intrigued to hear that these images were created 250 years before Mantegna’s painting existed, and so began our collaboration to place this work in historical context and share the story of how an Australasian cockatoo reached Europe in the mid thirteenth century.

The four images in the Vatican manuscript have rarely been reproduced in print. Many scholars have relied on Casey Albert Wood and Florence Marjorie Fyfe’s English translation of De Arte Venandi cum Avibus, published in 1943 (there is a copy in Melbourne University’s Baillieu Library). But although Wood and Fyfe included many illustrations from the original manuscript, they did not include those of the cockatoo.

This meant that while many scholars, including me, were aware the Sultan had given a white parrot to Frederick II, few were aware there were surviving images of this bird.

While ornithologists have made various identifications of the cockatoo, its significance had never been explored in depth until my Finnish colleagues studied the drawings in situ in the Vatican Library. They looked closely at details, like the shape of the crest and the colouring, and concluded the cockatoo was likely to have been either a Triton or one of three sub-species of Yellow-crested Cockatoo.

This means that the cockatoo gifted to Frederick II was taken from the northernmost tip of what is now Australia’s mainland, New Guinea or the islands off New Guinea or Indonesia. Based on the fact that my colleagues found red paint flecks in the irises of all four images, they also surmised it was probably a female.

In the thirteenth century it was common for monarchs to exchange animals as gifts and the larger, fiercer or more rare the animal, the higher its prestige. In 1251, for example, the King of Norway presented a polar bear to Henry III of England (who kept a menagerie of exotic beasts in the Tower of London), which was allowed to swim in the Thames and catch fish.

Arts & Culture

Restoring one of the world’s rarest maps

Frederick’s tastes were a little more refined, however, and he preferred rare books or animals whose behaviour he could study. He had many diplomatic exchanges with the ‘Sultan of Babylon’, the fourth Ayyubid Sultan of Egypt (the Kurdish al-Malik Muhammad al-Kamil), who knew the emperor enjoyed falconry and was particularly fond of birds. An exotic ‘white parrot’ from what was then considered furthest India was therefore the perfect gift.

Cockatoos travel well with people, being gregarious and long-lived. In captivity, they can have lifespans of up to eighty years and Australian Greater Sulphur-crested Cockatoos have been known to live up to 120 years. The journey along trade routes would have taken years, and their chances of surviving would have been much higher than the majority of animals.

Although our part of the world is still considered the very last to have been discovered, this Eurocentric view is increasingly being challenged. As more medieval European, Middle Eastern and Asian texts and images are translated, digitised and made available to wider audiences, previously overlooked records and images (like Frederick’s cockatoo) are coming to light - heralding a new era in the understanding of our region prior to European settlement.

The waters to Australia’s north were busy trade routes with merchants buying and selling fabrics, animal skins and live animals. This is not always acknowledged because, while written histories record the strong influence India, China and the Arab world undoubtedly had on Southeast Asia, they tend to downplay the maritime achievements of indigenous Southeast Asians.

Yet, in the early 13th century, China’s growing trade with the region had led to the emergence of new trading ports in Champa, Sumatra and Java with goods moving in both directions between Southeast Asia and China, the Indian Ocean region and the Middle East. By this time, the rise of Islam in the Middle East had provided the merchants of the Eastern Mediterranean and Persia with a safe, common marketplace through which ran numerous silk roads.

Although this trade lessened from the mid thirteenth century due to circumstances within China and India, records show that during the early thirteenth century Malay ports were exporting goods from other Southeast Asian destinations into China and beyond - including white parrots.

Frederick II’s cockatoo provides a rare window into that world - a medieval world that was surprisingly interconnected.

Banner image: One of the four images of the cockatoo gifted to Frederick II by the ‘Sultan of Babylon’. Codex Ms. Pal. Lat 1071, folio 18v (© [2018] Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana). For a high resolution colour image see article published in Parergon 35/1 (June 2018): 35-60.