Sciences & Technology

Photon teleportation: Less ‘beam me up’, more 007

A new way of pulling particles with light may sound like the stuff of science fiction, but it’s real and has the potential to make biopsies less invasive

Published 12 September 2024

Most of us would only associate ‘tractor beams’ with sci-fi movies like Star Wars and Star Trek.

And while it’s unlikely that we’ll see a spaceship being sucked into a mothership in real life, scientists can now easily produce a laser beam that draws particles towards itself – like a tractor beam – at the microscopic scale.

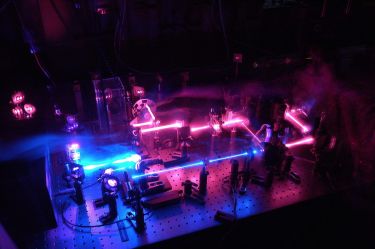

Early demonstrations of tractor beams were performed by physicists at New York University about 14 years ago. A rotating ‘solenoid beam’ of light was tilted in such a way that it produced a force towards the source of light that could pull microscopic silica particles through water.

Since then, optical engineers and scientists around the world have been busy trying to advance the technology, exploring how it can be developed and used in new ways.

The early examples of tractor beams were created using equipment that was sophisticated but bulky – and very costly.

Now, our team has pioneered a much simpler way to generate tractor beams.

Sciences & Technology

Photon teleportation: Less ‘beam me up’, more 007

‘Solenoid beams’ are special laser beams that consist of patterned light beams that rotate around the light source in a helix shape.

Working with colleagues at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Transformative Meta-Optical Systems, we’ve been able to generate a new type of solenoid beam that also works as a tractor beam.

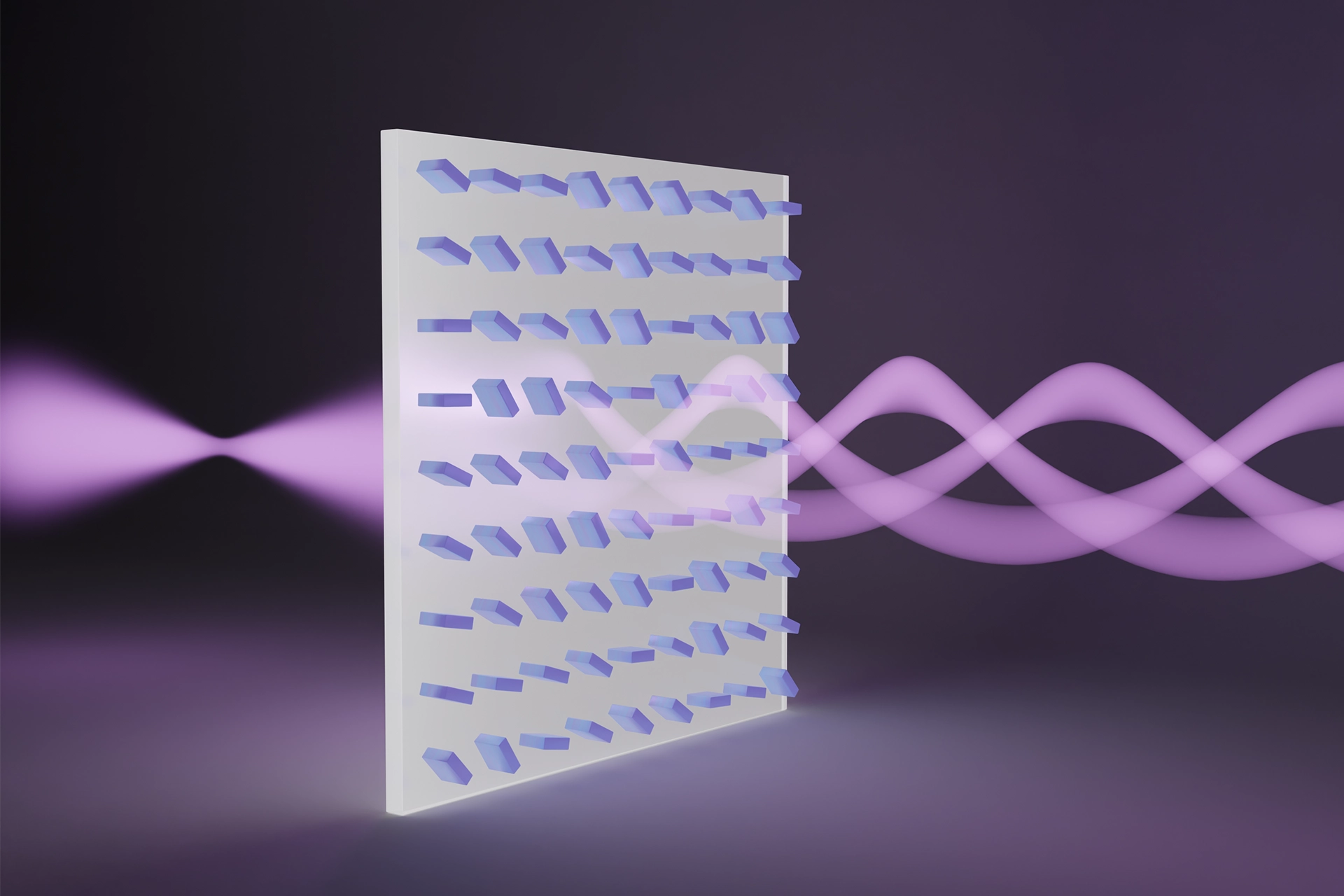

Our solenoid beam has a triple helix shape (consisting of three rotating beams) and is generated by passing a regular laser beam through a specially designed silicon surface.

To generate this kind of beam, we created a patterned ‘metasurface’ made of silicon nanostructures on a glass plate.

These nanostructures are incredibly thin at around 1/2000th of a millimetre and resemble miniature fins in varying orientations. Each fin transforms part of the laser beam to modify its properties so that the output is a solenoid beam.

Existing solenoid beam technology produces beams using bulky spatial light modulators, which can weigh several kilograms and cost thousands of dollars. Our silicon-on-glass metasurfaces have the advantage of being much smaller and cheaper to manufacture.

This opens up the potential to use these solenoid beams in a wider variety of applications, including in small, portable devices.

Think of it like a nail versus a drill. Strong beams of light, like a nail, tend to exert a pushing force, moving particles away from the light source (or hammer).

In contrast, the rotation of the light in tractor beams draws particles toward the light source, like how a drill works by pulling wood shavings up the drill bit.

Sciences & Technology

The exciting future of light energy

Tractor beam technology has the potential to be used in several fields.

It could, for instance, be useful for sorting and transporting micro and nanoparticles (in the range of one billionth of a metre to one-thousandth of a metre). These nanoparticles have applications in drug delivery, electronics or even in removing hazardous substances from the environment.

Another possible application is in biopsies, which involve extracting a small portion of tissue from a patient’s body to help diagnose diseases.

Whereas existing biopsy tools like forceps cause trauma to surrounding tissues, we hope that one day our tractor beam technology will enable non-invasive biopsies by allowing for the extraction of very small samples from a patient almost painlessly, while still providing an accurate diagnosis.

Until now, the size and weight of equipment needed to create solenoid tractor beams have prevented their use in handheld devices. But our work is a step towards making this possible in future.

The short answer is no. We can now achieve tractor beams at the microscale, but being able to move large objects in this way – like a spacecraft out of Star Trek or Star Wars – is well beyond the present scientific horizon.

However, using light to push spacecraft is an active area of development.

Sciences & Technology

Sounds like science fiction

The Starshot Breakthrough Initiative was established in 2016 with the goal of using giant ‘light sails’ pushed by lasers to send spacecraft beyond our solar system to a neighbouring star.

It would be nice to then be able to slow down or even reverse such a spacecraft, but that is unlikely in the foreseeable future.

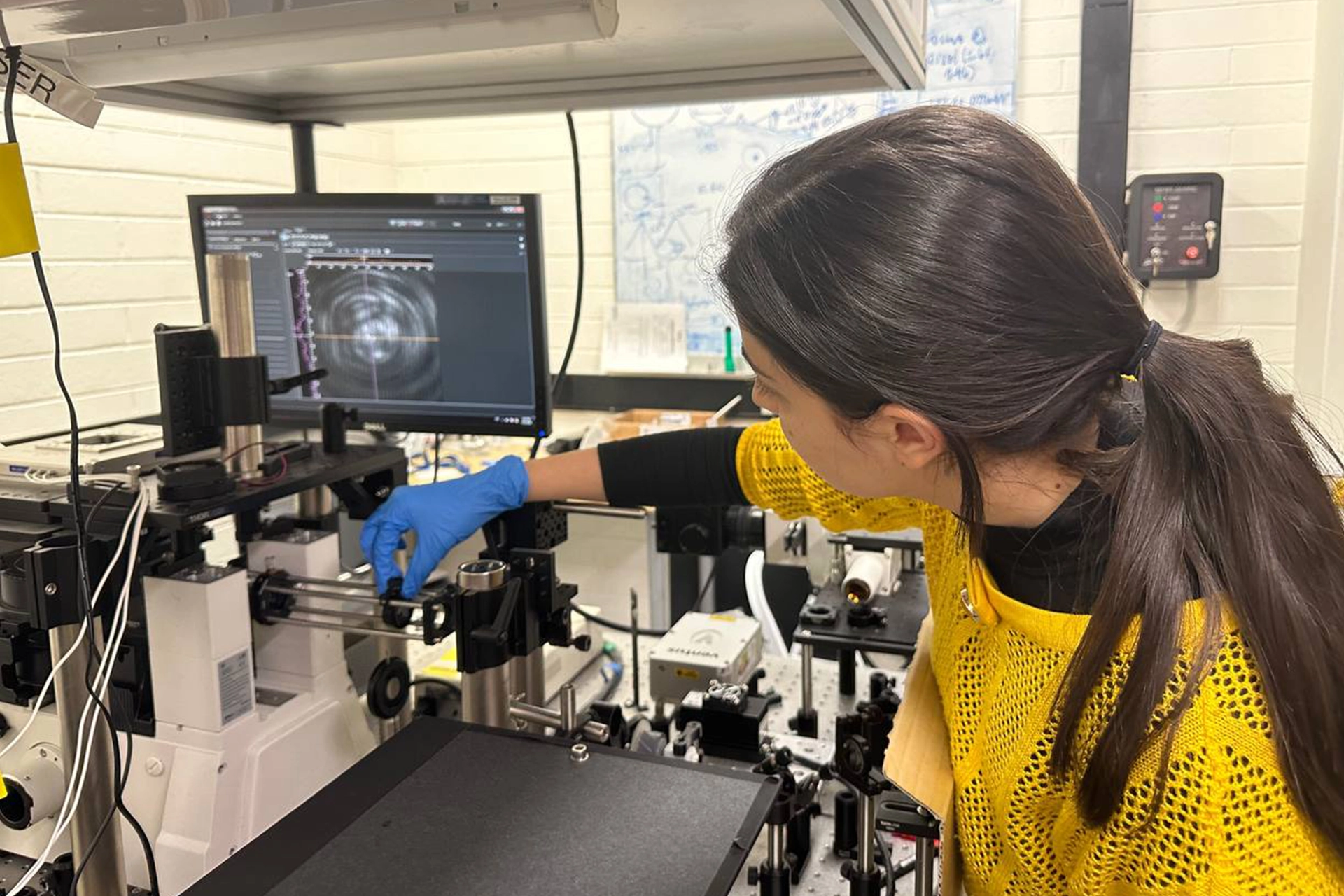

The next stage of our research will be to demonstrate experimentally the beam’s ability to pull particles, and then further develop these systems for practical uses, like biopsies.