Arts & Culture

Dying apart, buried together

Major historic events like 9/11 seem to demand monuments, but for many communities, smaller, more intimate memorials can provide a closer connection

Published 7 September 2021

Historical world events make you think back. For those who experienced them, the moon landing, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and 9/11 can conjure up the very specific time and place where we first received the news.

The anniversaries of these events then go on to scaffold our lives.

On the tenth anniversary of the 9/11 terror attacks on the US, I was working for a not-for-profit in New York. Each day on my way to work, I walked by an old shop window where the owner had taped up the front page of the Brooklyn Paper from immediately after the attack – “Infamy” read the 72-point headline, now in tatters.

This ad hoc memorial reminded me of the limited vocabulary used to commemorate the attacks in their immediate aftermath.

The media resorted to borrowing words from the Pearl Harbor attack a half century earlier – ‘infamy’, ‘horror’ and ‘never forget’. The vocabulary of grief and commemoration, both verbal and visual, needs time.

The process of memorial-making and commemoration is aptly defined by the novelist Milan Kundera’s famous maxim, as a “battle against forgetting.”

Arts & Culture

Dying apart, buried together

Public memorials are mostly associated with massive architectural and sculptural forms – objects that suggest permanence, made from stable materials, and placed in public spaces where they can’t easily be ignored.

For this reason, public sculpture, statuary and earthworks are the most familiar forms of memorialisation across a variety of cultures.

The creation of new memorials comes in ebbs and flows. The unification of Germany in 1871 eventually produced so many equestrian sculptures and fountains that editorial cartoonists proposed second uses for them – bays for mailboxes, drinking fountains and other badly needed amenities in the growing city.

While not actually functional, these 19th century monuments did serve to anchor newly-developed urban spaces, and they brought home the wars of unification to publics far from the battlegrounds.

Nation-building movements used bronze and stone to construct public memory and to shore up their ideological foundations.

This is certainly true for Australia, where the Anzac story is both heavily mythologised and cemented in national consciousness through interventions in the built environment, including The Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne, a building that, at its dedication in 1934, could be seen from most parts of Melbourne.

In the post-World War II era, the victory columns and triumphal arches that had typified past memorials were critiqued as “tawdry” and “overly effusive”.

Instead, a new generation of architects sought to build “living memorials” in the form of stadiums, auditoriums, community centres, pools and parks.

Politics & Society

Caste and cricket: How celebrities enable inequality

But while eminently useful, they were not good spaces for reflection – their utility overshadowed their purpose – and their popularity revealed the post-war era’s general discomfort with commemorating death.

The arrival of high-profile, blind competitions for memorials marked another turning point, marked by the 1981 selection of Maya Lin, then a 21-year-old architecture student, as the designer for Washington’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

Then in 2004, a design by Michael Arad, a 34-year-old architect working for an unglamorous city agency, won the World Trade Center Site Memorial Competition from a pool of more than 5,000 submissions.

Both processes were met with considerable controversy.

While not explicitly anti-monumental, site-based memorials like Lin’s were often perceived as such by the media. Her design, while celebrated today, was initially slammed.

The two descending slabs of marble were described as a “crypto-defeatist emblem of shame.” And Arad’s design went through five years of contestation and revision before the memorial finally opened in 2011.

Big memorials often generate highly-public fights over representation, built form and the very nature of memory.

The public meltdown over the 1995 design competition for Berlin’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe became front-page news in Germany, and issues with the final memorial continue to be newsworthy to this today.

The memorial comprises 2,711 concrete slabs covering 19,000 square metres. But in the context of remembering the Holocaust, perhaps bigger isn’t always better.

Arts & Culture

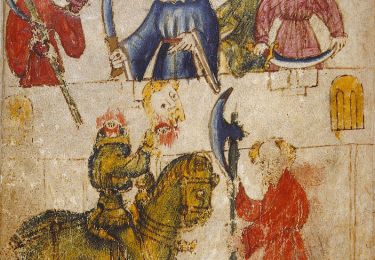

The poem behind the Green Knight

A good example comes in the form of stolpersteine (stumbling stones) – brass plaques set in the footpath in front of homes where Jewish residents once lived across Germany.

The project is the initiative of one artist, Gunter Demnig, who has made it his life’s work and has expanded it to over 15 European countries; the stones also commemorate LGBQT+ and Roma citizens who were killed by, or forced to flee from, fascism.

While the commissioning of memorials at grand-scale fulfils the need of elected officials to cement their own legacy, it doesn’t always protect against forgetting. Like giant tombs, these structures can seal history off.

Starting in 2009, New York’s Port Authority, owner and manager of the Ground Zero site, distributed pieces of steel that had been held back after the attack for archiving and investigation (the vast majority of the steel – over 200,000 tonnes – was recycled as scrap metal in the months after 9/11).

Museums, firehouses, parks and local councils all received pieces of the buildings’ steel skeleton that ranged in size from that of a briefcase to a barn door.

Many of these memorials are presented without fanfare, focusing on the ‘relic’ quality of the steel and encouraging passers-by to touch. The designs run the full gamut from over-the-top patriotic displays of stars-and-stripes and soaring eagles to understated forms that borrowed from the Land Art movement.

As all eyes turn to Lower Manhattan to mark the 20-year anniversary of 9/11, many will overlook the nearly 2,000 local memorials made from salvaged World Trade Center steel that are spread across the United States and, to a lesser extent, the world.

Over the past two years, I’ve been working with the sociologist Max Holleran to document these simple structures. Their distribution to small towns and suburbs helped connect communities to a tragedy that, at first, felt distant and difficult to fathom.

Arts & Culture

Bringing new life to cemeteries

Many of them are made from steel and concrete with modest budgets in conjunction with local fire departments and with the help of craftspeople. The tactile presence of steel reorients memory away from the images of the towers’ explosion and collapse and toward the materiality of their existence.

These micro-memorials point to the need for commemorative sites to be locally managed and to serve the community, rather than just symbolic, purposes.

We should pause to consider this as we re-consider our many monuments dedicated to highly-problematic figures that reflect past attitudes to imperialism, colonialism and racism, as well as proposals for COVID-19 memorials.

Monument-making is, above all, a process and it’s one where small-scale gestures often have the most significance.

Banner: City officials in Los Angeles lay hands on a steel column salvaged from the World Trade Center as part of a 9/11 remembrance ceremony marking the 10th anniversary/Getty Images