How the far right weaponised gamers and geek masculinity

Gaming culture didn't accidentally become male – it was deliberately marketed that way, creating the blueprint for online harassment that helped build the online far right

Published 7 October 2025

Earlier this year, Elon Musk was accused of cheating to fake his ranking in the action role-playing video game Diablo IV. At first glance, it looks ridiculous.

Why would the world’s richest man and a political influencer care so much about his gamer status?

But that obsession reveals something bigger. Games are not just entertainment. Games are political. Games are status symbols, battlegrounds for identity and tools of power.

Look closely and you see it everywhere.

China restricts children to one hour of online gaming on Fridays, weekends and holidays, framing play as a matter of national discipline. Russia has used doctored videogame clips as fake ‘evidence’ in its propaganda wars. South Korea built a global brand around StarCraft and eSports, positioning itself as a digital superpower.

From training soldiers to entertaining presidents, games have always carried political weight.

But it’s not only on the world stage that this plays out.

The everyday politics of gaming are equally potent. At the heart of this story is how games became gendered and how a culture that defined itself as male-only went on to make online misogyny mainstream.

From family fun to boy’s club

The sexism of gaming culture didn’t just happen. It was manufactured. Until the 1980s, women pioneered and dominated the field of computer programming.

In the 1970s, consoles like the Atari 2600 were advertised to families. But after the video-game industry crash of 1983, companies rebuilt by narrowing their audience.

With child advertising restrictions lifted, games were sold directly to boys as toys.

Magazines in the 1980s and 1990s sealed the deal.

As research shows, gaming media actively created ‘the gamer identity’: competitive, masculine and suspicious of anything that looked soft or feminine.

This wasn’t a natural identity that emerged from the games themselves. It was constructed, word by word, image by image, in magazines and adverts that mocked girls, fetishised difficulty and tied gaming skill to manhood.

While girls and women play as much or more than boys and men; girls and women are far less likely to identify as ‘gamers’.

Girls, meanwhile, were corralled into the ‘pink and purple’ games of the 1990s and early 2000s.

Titles like Barbie Fashion Designer didn’t challenge male dominance, they incidentally reinforced it by creating a subcategory of ‘girl games’.

Arts & Culture

All the world’s a game (and we are all players)

By the 2000s, if you didn’t fit the narrow image of the ‘hardcore gamer’, you were treated as an outsider. ‘Casual’ gamers were ‘fake gamers’.

That exclusion didn’t stay confined to magazines. By the 2010s, it exploded online.

When gender-based abuse went viral

The misogyny of the gaming community reached a breaking point in 2014 with the advent of Gamergate.

Under the guise of a crusade for ‘ethics in games journalism’, in reality Gamergate was an unprecedented mass harassment campaign of coordinated attacks against women and gender-diverse individuals in games.

This included indie developer Zoë Quinn, feminist media critic Anita Sarkeesian, journalist Leigh Alexander and actor Felicia Day.

In fact, Gamergate emerged from intimate partner gender-based abuse, with Quinn’s ex-boyfriend, Eron Gjoni, sharing his 10,000-word blog to forums like 4Chan and Reddit with the openly admitted intention of destroying Quinn’s life.

And things escalated quickly – because it fed directly into a culture already primed to suspect non-males as ‘fake gamers’, and Quinn’s game, Depression Quest, didn’t fit the macho hardcore definition of what counted as a ‘real game’.

Part of the motivating force behind Gamergate was the ‘geek masculinity’ that underpins much of the gaming community.

This kind of masculine identity positions itself in contrast to (and victim of) the ‘jock’ stereotype, à la Revenge of the Nerds. This sense of victimhood, whether real or perceived, is used by geeks to justify their victimisation of others.

Arts & Culture

Gaming can be a machine for empathy

Targets of Gamergate were subject to doxing, stalking, bomb threats, campus massacre threats and graphically detailed threats of rape and death sent in the hundreds of thousands.

Gamergate was not the first online coordinated harassment campaign, but it was the most visible and widely reported, amplified by several extremist far-right figureheads including Steve Bannon (then Breitbart News Executive Chairman and Chief Strategist for Donald Trump’s 2016 election campaign) and Milo Yiannopoulos (Editor of Breitbart News and far-right political commentator).

A decade later, Gamergate’s legacy lingers.

It laid the groundwork for the manosphere, and its weaponisation of networked harassment in the online culture wars was absorbed into the far-right and helped elect Donald Trump into the White House.

Play differently

Games inherit the logics of the military, the gatekeeping of the magazines, and the hostility of the internet.

But that doesn’t mean they are doomed. It means we should expect more from them.

Today, gaming is more diverse than ever. Cozy games like Animal Crossing, mobile puzzle hits like Candy Crush, and indie darlings like Unpacking show us that games can be gentle, creative and inclusive.

Feminine Play and Pride at Play showcase that games can be feminine and tell LGBTQ+ stories.

In Australia, where the big-budget industry collapsed after the 2008 financial crisis, small studios have flourished.

Making a game here is often more like starting a band with friends than in big studios.

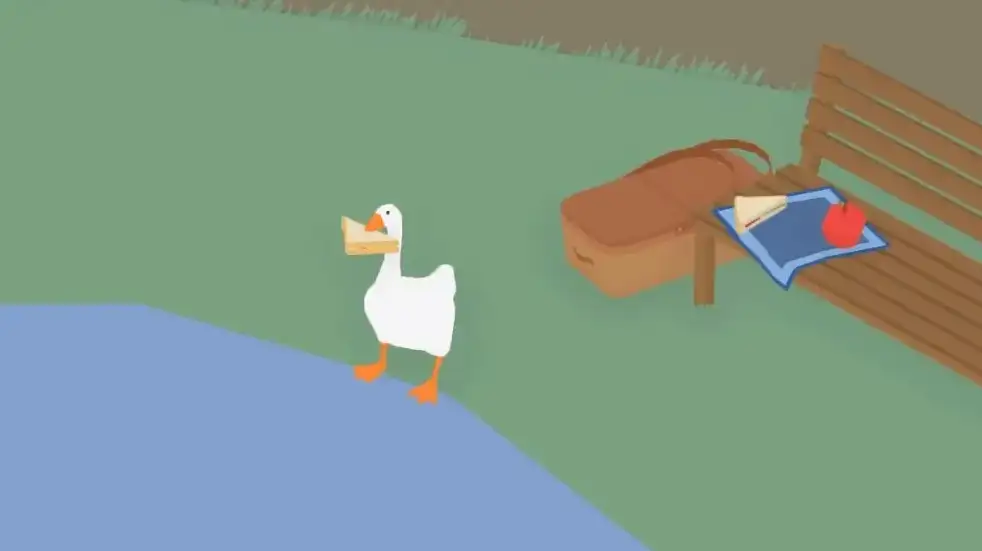

The result is titles like Untitled Goose Game, celebrated for humour and originality rather than pandering to an imagined ‘hardcore gamer’ audience.

Politics & Society

Video games are building worlds beyond the laws of physics

This creativity is on show at Melbourne International Games Week, where indie booths at PAX and Freeplay reveal a creative arts scene brimming with ideas.

These are the futures we should be investing in – not just financially, but culturally.

And so, we come back to Musk and the revelation that he is what many girls and women have long been accused of: a fake gamer.

His fixation is not just ego. It’s emblematic of how gaming has become a marker of masculinity, credibility and political capital.

From Gamergate to propaganda wars, from eSports diplomacy to billionaires chasing clout, games are woven into the fabric of our global and everyday politics.

Games are political. The question is: what kind of politics do we want to play?

If you need help and advice, visit the eSafety Commissioner or the National Office for Child Safety websites. If you are seeking help to leave a hate group, you can contact Life After Hate for support.