Health & Medicine

This has so rarely occurred in the University’s history

An Indigenous-led book challenges the presumption that universities make only ‘good’ contributions to the community – confronting the University of Melbourne’s disturbing history

Published 28 May 2024

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains images and names of people who have died. It also includes distressing descriptions and derogatory terms for Indigenous people used in their historical context.

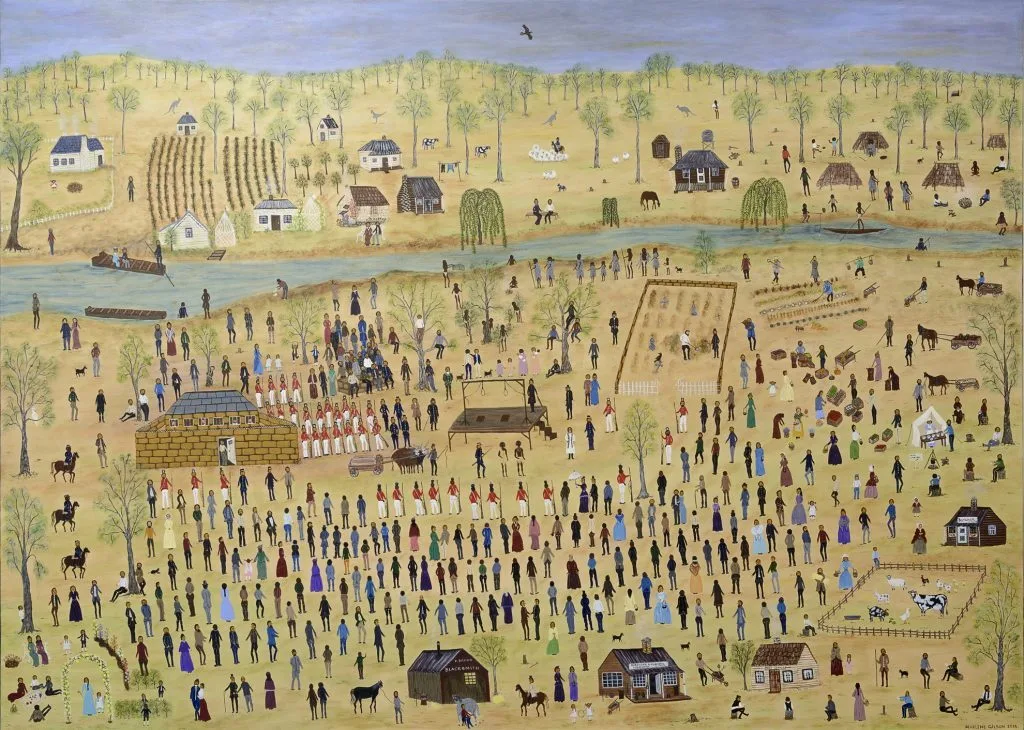

The University of Melbourne was established in 1853, during Victoria’s colonial era, and its first leaders were also leaders of the colony. Sir Redmond Barry, regarded as the University’s founder, also founded the State Library of Victoria.

He was a judge, and perhaps best known for imposing the death sentence on Ned Kelly. We are more interested in his role in 1841 as defence lawyer for two Aboriginal men accused of murder.

In the case of Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner, Barry argued what may now be regarded as the foundations of the recognition of Indigenous peoplehood and native title, interrogating the legal basis of British authority over Aborigines who were not citizens.

He also argued that the evidence against them was dubious and circumstantial.

Despite his defence, they were found guilty and hanged on 20 January 1842, becoming the first people in Victoria to be legally executed.

In this way, the beginning of a highly contested history of the University began, with those sympathetic to the situation of the First Peoples, and those whose actions and attitudes were aimed at eliminating Indigenous peoples.

Health & Medicine

This has so rarely occurred in the University’s history

Acknowledging this contested history is the work of the Indigenous History of the University of Melbourne project, established in 2020. This project is revealing the significance of the University’s past connections with Indigenous Australians, its most egregious events and its gradual reforms.

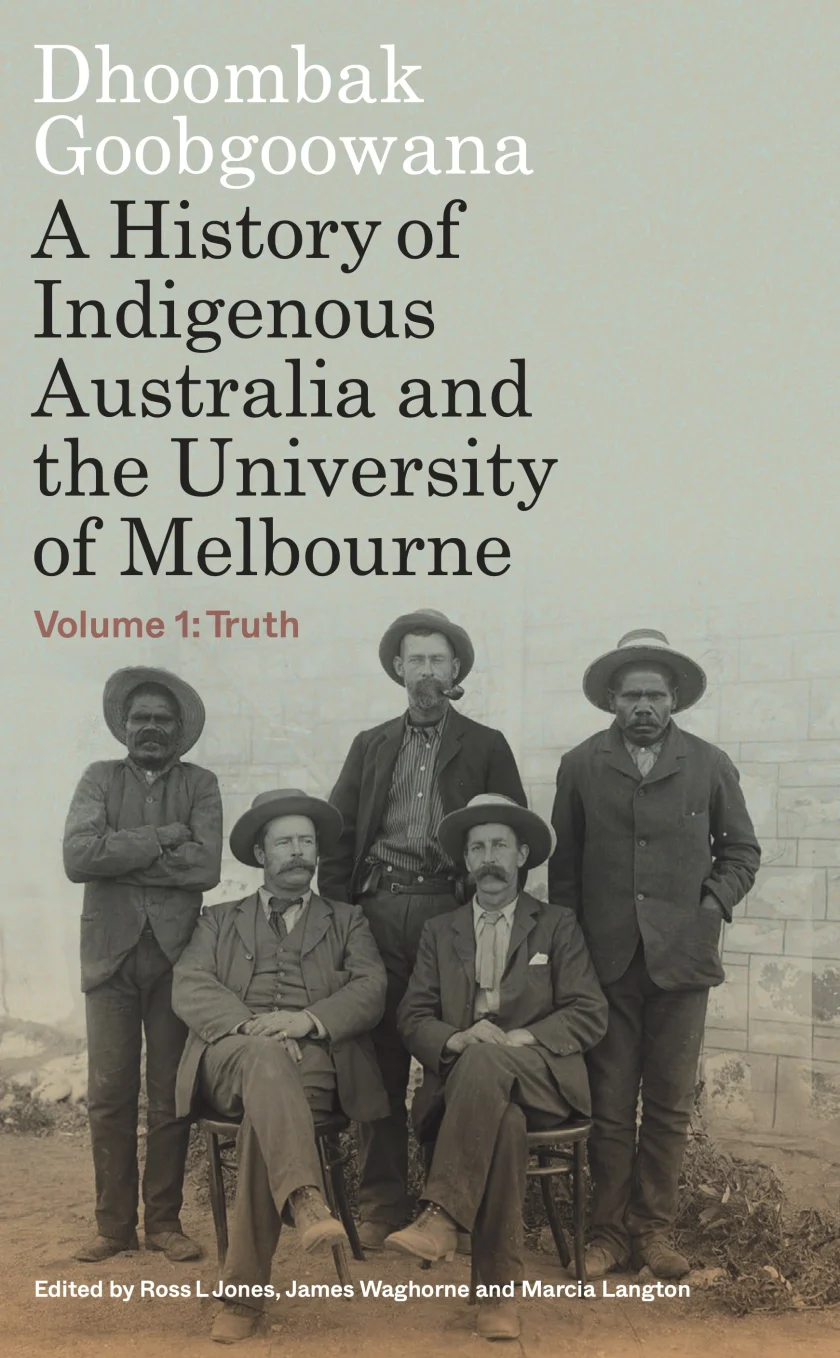

This project has led us to publish a new history of the University, Dhoombak Goobgoowana – A history of Indigenous Australia and the University of Melbourne.

One divisive example of this history was the 2016 decision to rename the Richard Berry Building.

Berry’s story highlights problems with the University’s long connection with Indigenous Australia.

Berry was a Professor of Anatomy between 1905 and 1929 and Dean of the Medical School in his last four years. He enjoyed widespread acclaim as a public intellectual in his lifetime.

But from the 1990s, scholars uncovered his role as a leader of the eugenics movement in Australia. Eugenics was the widespread scientific theory justifying inequality between social groups and races.

His research work included studies of both living and dead Indigenous Australians, whom he classified as ‘sub-normal’ based on his comparison to non-Indigenous Australians.

He then applied these specious findings to influence public policy.

Acknowledging this contested history is the work of the Indigenous History of the University of Melbourne project, established in 2020. This project is revealing the significance of the University’s past connections with Indigenous Australians, its most egregious events and its gradual reforms.

This project has led us to publish a new history of the University, Dhoombak Goobgoowana – A history of Indigenous Australia and the University of Melbourne.

One divisive example of this history was the 2016 decision to rename the Richard Berry Building.

Berry’s story highlights problems with the University’s long connection with Indigenous Australia.

Berry was a Professor of Anatomy between 1905 and 1929 and Dean of the Medical School in his last four years. He enjoyed widespread acclaim as a public intellectual in his lifetime.

But from the 1990s, scholars uncovered his role as a leader of the eugenics movement in Australia. Eugenics was the widespread scientific theory justifying inequality between social groups and races.

His research work included studies of both living and dead Indigenous Australians, whom he classified as ‘sub-normal’ based on his comparison to non-Indigenous Australians.

He then applied these specious findings to influence public policy.

The legacies of a number of Berry’s contemporaries have also been challenged – including Professor of Biology Sir Walter Baldwin Spencer, education reformer Frank Tate and the Professor of Zoology, Wilfred Agar.

Our new and ongoing research, which is included in Dhoombak Goobgoowana, finds that Tate and Agar, along with Berry, advocated eugenic measures to limit the reproduction of people they referred to as having ‘inferior’ genetic stock.

This included Indigenous Australians.

At the same time, post-colonial scholarship criticised the role of anthropologists, like Spencer, in managing policies that brought harm to Indigenous people.

While he was Northern Territory Protector of Aborigines, Spencer oversaw child-removal policies.

He also had an interest in eugenics which led to his nomination as President of the short-lived first eugenics society in Victoria.

These examples challenge the presumption that universities make only ‘good’ contributions to the wider community.

Their image as unchanging ‘ancient’ organisations is also upended, as it becomes clear just how radically ideas of progress and public good can change.

After all, the activities of these celebrated men were central to their university and its public work and reputation. Berry, for example, had been supported for decades by the University, the Victorian government, the major newspapers and international philanthropic organisations like the Rockefeller Foundation.

These examples also offer new ways of understanding how the University’s history has been written. The Richard Berry Building was named in 1970 – long after Berry had left the University – but other buildings have been named more recently and are now, rightly, challenged.

The naming of buildings after great men was a way of celebrating the University’s history. However, our work is showing just how much of this story is incomplete. As a result, a fuller and more problematic history is being written.

The history, to be published across two volumes, covers all faculties and graduate schools at the University. As well as its racist past and eugenics, we explore the meaning of place and the University’s campus footprint from the past to the present, including the support of benefactors whose wealth was derived from pastoral runs on stolen Indigenous lands.

Dhoombak Goobgoowana also examines the University’s Indigenous collections, including human remains, art and cultural artefacts.

The books follow the University’s slow and uneven efforts to recruit and support Indigenous students and staff – tracing the emerging recognition of Indigenous knowledge, including the contributions of Indigenous people in the University’s past research work

The Indigenous History of the University of Melbourne project is overseen by an Indigenous standing committee chaired by Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous) Professor Barry Judd.

Currently, some seventy academics across all disciplines are contributing to the history – and around a third of these are Indigenous who are guiding, advising and leading the project, featuring testimony from Indigenous leaders like Uncle Jim Berg, Professors Ian Anderson and Marcia Langton AO among others.

Much of this history is disturbing and many past actions of the University and its staff are contemptible. But there are also examples that indicate the growing understanding of the need to repair and reinvigorate the University’s relationship with Indigenous Australians.

One example of the complexity the University faces is the Donald Thomson collection. This collection was assembled by the professor of anthropology over several decades of fieldwork with Indigenous communities in Arnhem Land, Central Australia and Cape York.

Thomson demonstrated empathy and understanding for the people with whom he worked and supported causes such as land rights and language protection, while also adopting anthropological practices that involved the collection of materials, including human remains (which are under the control of the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council).

The collection is one of the most significant contributions in the world and was listed on UNESCO’s Australian Memory of the World Register in 2008.

Under Indigenous supervision, the University is currently reconnecting the items in the collection with the Indigenous peoples they were removed from.

This complex exercise has required revision of policies to ensure that the University is compliant with Australian laws and long-standing international standards and human rights in relation to collections of Indigenous cultural heritage.

Importantly, this truth-telling project acknowledges the University’s contested past and is a first step towards formally acknowledging its institutional and colonial history.

Dhoombak Goobgoowana – A history of Indigenous Australia and the University of Melbourne – Volume 1: Truth is published by Melbourne University Publishing and edited by Dr Ross Jones, Dr James Waghorne and Professor Marcia Langton. Hard copies are available to purchase, and a free digital copy is available through an open-access portal.