Environment

A Big Build or a big bet?

Melbourne’s proposed bus program could change the city’s public transport system for the better, but it doesn’t quite go far enough

Published 20 December 2023

Melbourne has a bus problem. Which makes the newly released report from Infrastructure Victoria, Fast, frequent, fair: How buses can better connect Melbourne welcome – both for its attention to the often-neglected value of buses and the detail in the report.

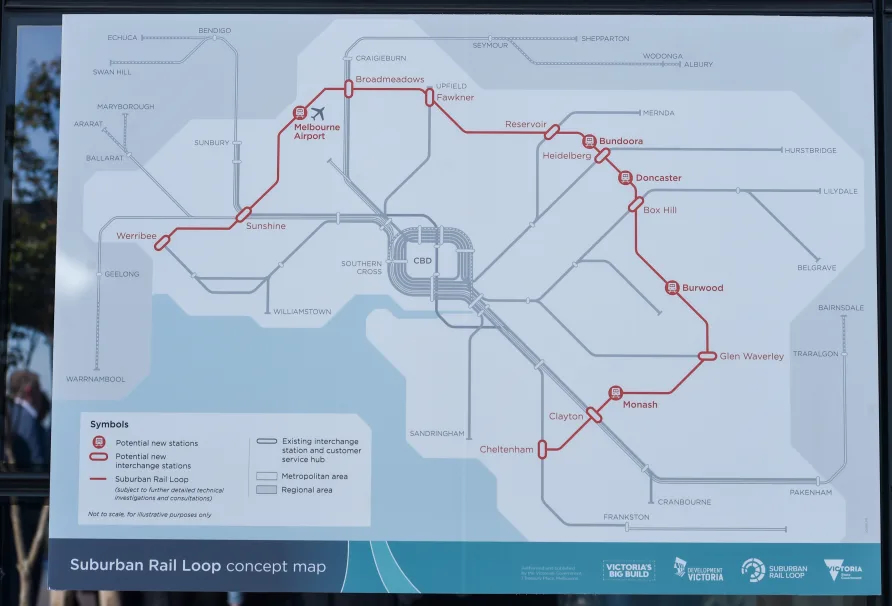

This is evidence-based policy, as distinct from the ‘lightbulb-based policy’ that resulted in Melbourne’s wasteful Suburban Rail Loop.

The case for ‘better buses’ in Victoria is well and truly overdue – and there’s inspiration in the quality bus services already established in many cities around the world.

The report offers recommendations for the Victorian Government to improve bus services that can serve a mass transit function – a term used to describe efficiently moving large numbers of people to activity centres.

The emphasis is on city-wide improvements to the frequency, coverage and operating hours of buses as well as improved speeds. And the report also highlights the need to improve many important services around bus usage – like improving bus stops, vehicle accessibility and service information.

Environment

A Big Build or a big bet?

The report urges the introduction of bus services as people move into new housing in Melbourne fringe developments, an important initiative for a growing population.

All up, the package provides a comprehensive vision of how buses can cost-effectively support a more sustainable Melbourne.

Starting these improvements in outer suburbs and growth areas – where bus services are lagging considerably behind population growth – is also important.

But there are two main concerns with the directions the report is proposing.

The first is the apparent splitting of public bus transport into mass transit and community transport. Community transport is currently an ad hoc service provided by welfare and health services.

The second is the lack of focus on how the proposals can support Plan Melbourne’s intention to develop 20-minute neighbourhoods – these are neighbourhoods designed to enable people to meet most of their daily needs within a 20-minute walk, cycle or public transport trip from home.

The report proposes restructuring Melbourne’s bus services based on a new set of route categories: rapid routes, shuttle routes, trunk routes, connector routes and local routes.

This restructuring and the associated proposed service enhancements will deliver significant benefits to bus mass transit users.

Politics & Society

How can we open up Melbourne while tackling disadvantage?

Walking distances to bus routes are planned to increase in line with more direct bus routes. This will not trouble most people but will be a barrier for many.

For example, those with heavy shopping loads and Australia’s aging population who may find the walk difficult – as well as the increasing (and necessary) recognition of the need for mainstream transport equity for those with a disability.

The report suggests these customers will use an expanded community transport service, for travel around the local neighbourhood.

The report is proposing, in effect, a dual road-based public transport system, made up of an expanded bus service for mass transit and an expanded community transport service for local travel.

However, mass transit, local public transport and community transport should all be part of a single public transport system.

The two bus transport systems suggested in the report offer an ableist approach that segregates the community, loses the concept of inclusion and moves against current trends that recognise the importance of equity of opportunity.

It’s also contrary to the idea of integrated transport planning.

A better solution would be to roll Melbourne’s current community transport into one integrated public transport offering.

Local public transport is a cornerstone of Plan Melbourne’s thinking behind 20-minute neighbourhoods. Having separate mass and community transport services operating at local level will add unnecessary complications to this planning.

And any thinking over a 20-year planning period should start with neighbourhood development, to reduce the need to travel, with local public transport a vital element.

In this regard, Infrastructure Victoria’s proposals are a step backwards.

More broadly, there is a need for much stronger connections with Plan Melbourne. This should facilitate the linking of transport with reducing Melbourne’s sprawl by increasing dwelling and service density, establishing 20-minute neighbourhoods and using improved mass transit bus services.

It should accelerate growth of Plan Melbourne’s seven National Employment and Innovation Clusters, essential for a more compact city.

On a more technical level, our research, which seems to have been used in the report to value transport improvements for those at risk of social exclusion, has been used conservatively.

The ability to move around easily has value beyond what is considered in this report. Mobility can facilitate social capital and connections to community, both critical components for personal and community inclusion and wellbeing.

The dollar value of these social attributes is high, in terms of personal and societal gains, the latter by reducing the costs of disadvantage expended in welfare and health systems.

A measurable trend in Melbourne is for lower income households to move to more affordable outer suburbs. While the housing is more affordable, it is also where there are currently fewer bus services, longer commutes and delayed provision of many other community services.

And so socio-economic exclusions become entrenched.

In short, the benefits of the proposed bus program will probably be larger than Infrastructure Victoria suggests – but so will the societal costs of cutting any local public transport service opportunities.

This report presents serious evidence-based policy opportunities to improve the sustainability of Melbourne’s public transport services, unlike the case for the Suburban Rail Loop.

So moving resources from the Suburban Rail Loop to implement the priorities in the Infrastructure Victoria report, along with the amendments we’ve talked about, would leave plenty in the bank, or on the state’s credit card, for further transport and other social initiatives.

Banner: Shutterstock