Arts & Culture

How did a cockatoo reach 13th century Sicily?

The Jagiellonian arrases – tapestries that decorate the walls of Wawel Castle in Poland – may be one of the earliest known artistic representation of the long-extinct dodo

Published 6 August 2020

This month marks 500 years since the birth of Sigismund II August, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, who endowed his royal court with magnificent collections of art.

Among the collection is a group of richly woven Flemish tapestries that adorn the walls of Wawel Castle which sits in the middle of the Polish city of Kraków.

Most of these tapestries were commissioned by the king, who ruled between 1548 and 1572. He was the last male of the Jagiellonian Dynasty, a family of monarchs in Poland, Lithuania, Bohemia, and Hungary – one of the most powerful in eastern central Europe.

Over the centuries, this collection of tapestries has been referred to as the Jagiellonian arrases, taking their name from the dynasty and the town of Arras, in northern France, renowned for its production of tapestries.

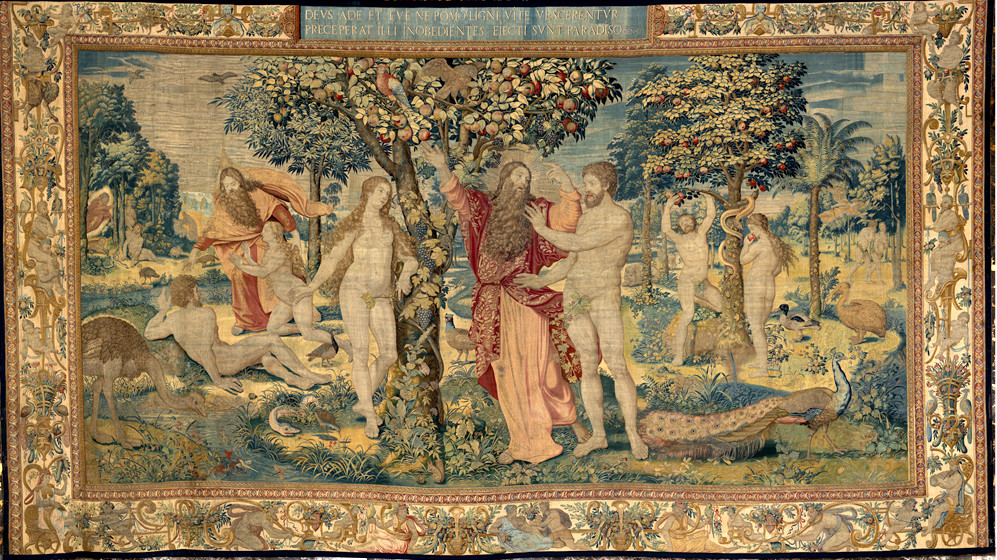

The Jagiellonian arrases are exquisite – telling the Genesis stories of Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Noah and the Tower of Babel. They feature exotic animals from around the world – peacocks, snakes, tigers and parrots.

Arts & Culture

How did a cockatoo reach 13th century Sicily?

But, surprisingly, they may also contain what might be the oldest known depiction of a dodo.

One of the Jagiellonian tapestries on the biblical theme of “the first parents” depicts five scenes: the moment of Creation, God’s introduction of Eve to Adam, God commanding Adam and Eve not to eat the fruit from the tree of knowledge, the action of the original sin; and finally, the scene of expulsion from Paradise.

The first known account of these tapestries, by Polish courtier and writer Stanisław Orzechowski, was published within a month of their unveiling.

He wrote that, following the wedding of Sigismund II August and Catherine of Austria, on 30 July 1553 “…there was revealed an extraordinary magnificence of tapestries which, it appears, had never been seen in the palaces of other kings”.

The wedding guests were shown the tapestries which had been hung in the castle’s spacious and well-lit reception halls and rooms, located on the upper floors. Orzechowski describes vivid figures, noting their richness “brocaded in gold” and their painting-like realism; “There, as if they were alive”.

Arts & Culture

Restoring one of the world’s rarest maps

Of the first tapestry, the Garden of Eden, he writes, “stood Adam and Eve, our first parents as well as the ones responsible for our ills, painted by the weaving art”.

Orzechowski calls the tapestry the Bliss of Our Ancestors, but he does not mention the dodo.

The tapestry featuring the landscape of the Garden of Eden is full of European and non-European animals and birds and, like the people, are life-like.

Sitting among these exotic creatures is a bird, which may be a dodo – a now-extinct flightless bird that lived on the island of Mauritius.

The English writer Sir Thomas Herbert was the first to use the word ‘dodo’ in print in his 1634 journal, claiming the bird was referred to as such by the Portuguese, who had visited Mauritius in 1507.

But less than two centuries later, the bird was extinct – the last accepted sighting of a dodo was in 1662.

If the bird in the tapestry is a dodo, it would make this the oldest extant image of a dodo.

But its depiction may also tell us that along with the other source material the Flemish artists must have used, they also had access to images of the dodo taken from life.

The dodo-like bird woven on the Jagiellonian tapestry is located towards the edge of the scene, just above a male peacock with magnificent plumage. Its beak is facing the centre of the tapestry, as if witnessing Eve reaching for the apple.

In contrast to the brightly coloured peacock, this bird is made up almost of one colour with brownish-grey plumage. It has a large body, small wings, short legs and a large curving beak.

Its representation here is similar to the portrait of a dodo by Flemish artist Jacob Hoefnagel sitting among the menagerie of Emperor Rudolph II in Prague in about 1602.

Although the bird on the Jagiellonian tapestry is hardly plump, it’s a subtle representation that blends into the background of the biblical scene.

But, as interesting as it is to speculate, we can’t be sure that the bird in in the tapestry is actually a dodo – there are no comparative images of the bird made in the years preceding the manufacture of the tapestry.

The closest representations of the dodo were made about 50 years later.

The image is also different in certain ways from paintings of the dodo produced by, for example, the Flemish artists Jan and Roelandt Savery, who depicted the bird over the course of the seventeenth century as obese with stubby wings.

Although some live dodos were brought to Europe in the early 1600s, in the art world, there remained a degree confusion about the birds’ appearance.

The main collection of the Flemish tapestries held in Kraków includes 19 epic tapestries which correspond thematically to the biblical stories designed at the king’s request by the Flemish painter, Michiel Coxie (de Coxien).

The theme of the tapestries was most likely chosen by King Sigismund II August himself and were woven with wool, silk, silver and gold threads in Brussels workshops of leading weavers Pieter II van Aelst, Willem and Jan de Kempeneer and Jan van Tieghem.

These workshops produced tapestries much sought after by the courts of Europe in the first half of the 16th century, depicting monumental pictorial representations.

In addition to the arrases with the biblical themes in the Kraków collection, there are also 44 verdure tapestries designed in Antwerp.

Arts & Culture

The oddities of existing things

These feature scenes from forests and woodlands, landscapes with animals as well as 12 tapestries arranged with heraldic themes representing the coats of arms of Poland and Lithuania, and the royal cypher of Sigismund II August, the letters ‘S.A.’.

The majority of the 142 surviving arrases of this collection are still on display in the Wawel Castle and, today, form one of the most extensive collections of tapestries in the world.

But these tapestries not only tell us about the splendour and riches of the Jagiellonian dynasty, they tell us about ideas.

The art itself provides an insight into the transmission of ideas across national and linguistic boundaries in the centuries before the world was divided by the bi-polar allegiances to the West or East.

Both the tapestries themselves and their endurance are also a testament to the close links within European culture.

So, it’s almost as an afterthought, that they potentially also give us our earliest artistic glimpse of an animal that has been extinct for more than three centuries.

Banner: Muzea Małopolska