It’s time to recognise the role masculinity is playing in the climate crisis

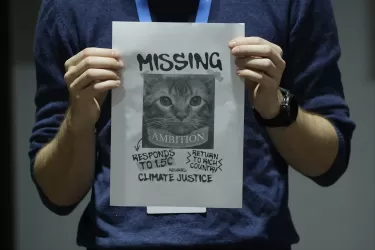

COP29 came to a fairly disappointing end. We need to address the role of masculinity in harms against nature

Published 3 December 2024

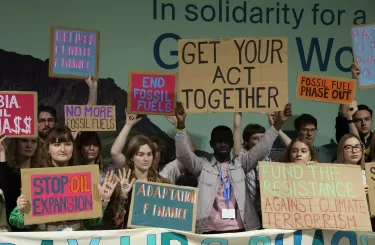

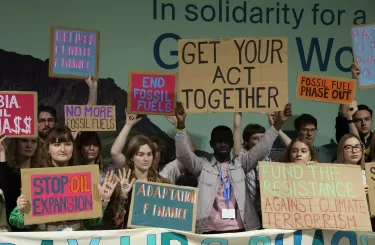

Now that the COP16 biodiversity and COP29 climate change summits have come to an end, one thing that is glaringly clear – as photos of world leaders notoriously show – is just how much these crucial conferences continue to be dominated by men.

This matters. Not just because we need women’s voices and experiences when decisions are being made about global warming. These predominantly male leaders have so far been either incapable or unwilling to turn the ever-deepening climate crisis around.

Indeed, the re-election of Donald Trump in the United States illustrates how some ‘strongmen’ politicians have sought to accentuate (in macho terms) their disregard for climate change.

This is epitomised in his oft-repeated slogan, “drill, baby, drill”.

Meanwhile, the COP conferences point to a lack of attention from policymakers towards how gendered and other social inequalities are exacerbated by the destruction of the environment – although these issues are starting to be discussed.

It’s time to consider not only how ‘natural’ disasters have a disproportionate impact on women, but also what part men are playing, and can play, in relation to global warming.

Conquering, hunting and meat eating

There is a lot of evidence that men are more likely to engage in environmentally damaging behaviours, including the tendency to have higher carbon emissions than women.

‘Conquering’ the environment by doing things like driving fast cars and hunting animals are still seen as powerful ways to prove one’s manhood.

So, in order to get to the roots of the climate and biodiversity crises, we must address the disproportionate role that ideas about ‘being a man’ are playing in driving them.

Caring for and about the environment is often still seen as weak and contrary to traditional masculine ideals of strength and self-reliance.

There also remain influential notions of what it is to be a man that discourage emotionality and vulnerability, which are crucial for acknowledging the interconnectedness of all life and the urgent need for collective action.

For many, being seen as a ‘real man’ requires severing oneself off from one’s emotions, which are often associated with femininity and nature.

This means refusing to acknowledge one’s own vulnerability, including in the face of impending disasters spurred on by the climate emergency.

The interconnectedness of gendered harms

Ecofeminists have articulated that these patriarchal ways of thinking are based upon hierarchies which value culture over nature, humans over other animals, rationality over emotion, mind over body, and masculinity over femininity.

This leads to a perception that the natural world consists of resources which we are entitled to endlessly extract and exploit, based on the notion that humans are separate from and superior to nature.

We can see this in behaviours like meat-eating, which is often seen as a symbol of masculine strength and virility. Men are less likely to adopt vegetarian and vegan diets, and those who do often face ridicule, labelled ‘sissies’ or ‘soy boys’.

The meat and dairy industries are major contributors to the climate emergency, as well as inflicting significant harm on animals bred for exploitation and slaughter.

Criminologists like us should recognise these destructive behaviours against other animals and the environment as harms in their own right, while also understanding how they interconnect with other gendered harms.

For example, there is evidence that levels of gender-based violence increase in communities that surround slaughterhouses.

The abuse of animals often plays a role in domestic violence.

These are just a few examples of how society’s gendered pressures and expectations are unsustainable with living harmoniously on this planet.

No matter how reluctant, and afraid, we might be to accept it, the climate and biodiversity crises demonstrate that all humans are fragile and vulnerable in relation to nature – as well as being reliant upon it.

A positive path forward

These crises must force us to consider new ways of being. This should not be seen as a loss – it offers positive paths forward for boys and men.

Recognising our interdependence and forging close relationships with other animals and the environment helps us to become more connected and rooted in the world.

This is something First Nations communities have long understood.

This can provide a route out of the loneliness, isolation and confusion that many boys and men feel.

There is plentiful evidence that being close to nature has positive effects on our health and wellbeing – and in turn, helps to galvanise concern for environmental issues.

Nature-connectedness should be incorporated more into our day-to-day lives, in schools and in work with men and boys.

Caring for our local environment and other animals can help us to feel part of our communities. It can give us a sense of agency at a time when many of us feel powerless about the multiple crises we are facing.

But, to do that, it’s vital to recognise that part of addressing these crises means freeing ourselves from the rigid gendered expectations holding all of us back – including notions that humans are ‘above’ other living beings.

The disappointments of recent COP conferences show that we cannot wait for our political leaders to take action – we must make transformations in our own lives and communities, as well as pushing for deeper social change.