Sciences & Technology

Why a cat’s whiskers are the bee’s knees

Fear-not; there’s no chance of pythons developing a taste for humans

Published 31 March 2017

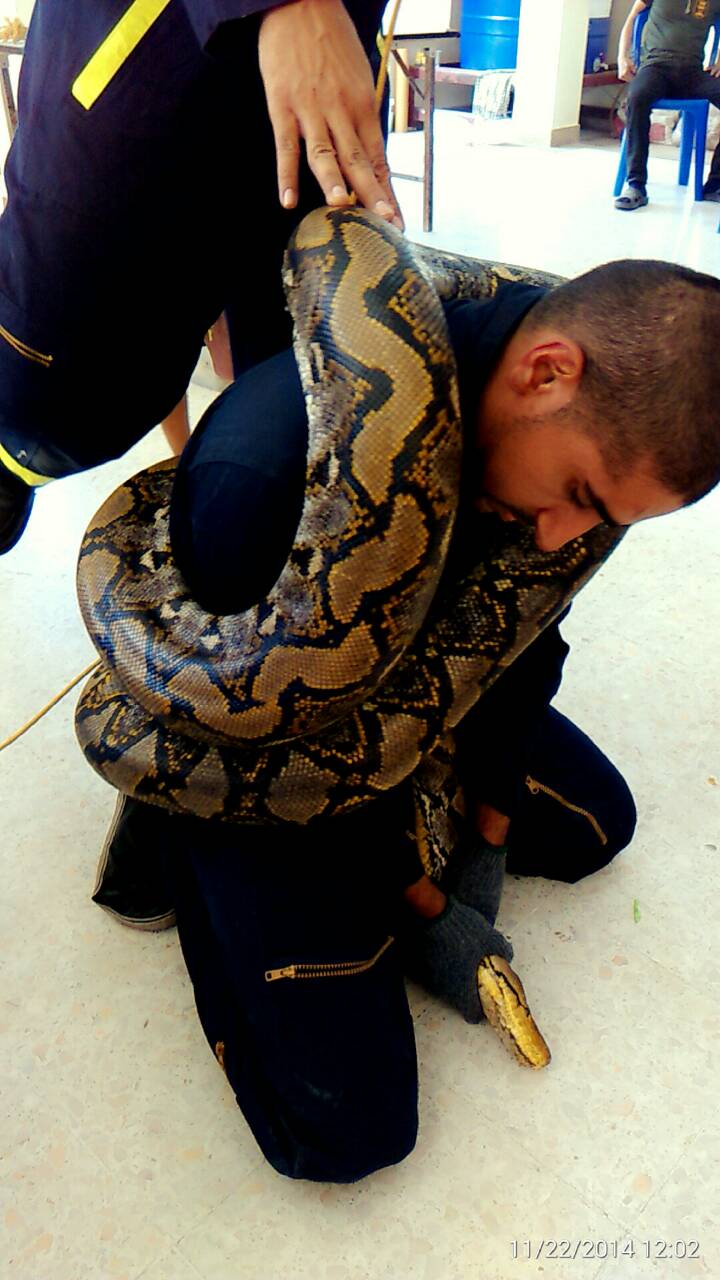

The news that a man was swallowed whole by a snake on an Indonesian island leaves more than an uncomfortable lump in the throat. Images that can’t be unseen – including a six-minute video of the snake being sliced open to unveil a fully-clothed, very dead human in its stomach – fuel the horror movie hysteria.

Dr Sasha Herbert, who runs the exotic pet unit at the University of Melbourne’s U-Vet Werribee, sees beyond the macabre in the demise of a 25-year-old Sulawesi palm oil plantation worker. While snakes eating humans is rare, Dr Herbert says it’s also merely an extreme example of nature at work.

“It’s awful for that person and the people around him. But it’s equally awful for the antelope to be eaten by the lion. Our world is a food chain. This isn’t anything special or unusual for an animal to do, it was just taking an opportunity.”

Setting aside the grisly YouTube footage, there’s fascination aplenty in the science of this tragedy. In short the why, and particularly the how. Dr Herbert, who worked in zoos for a decade including six years in Singapore, notes that the continuing creep of humans into the habitat of wild animals is an open invitation for such encounters.

“There’re fewer and fewer of these poor animals because we have encroached further and further into their habitat. Anywhere that you have a predator that’s big enough, you have the potential for humans to be their prey.”

In this case we’re talking an eight-metre long reticulated python that could weigh well in excess of 100 kilograms, depending on its fat storage (which in pythons can be very large).

Sciences & Technology

Why a cat’s whiskers are the bee’s knees

Dr Herbert says they are “ambush predators … not hunters”; they lie in wait for their meal, and in South East Asia dine on anything from rodents to deer and myriad mammals in between. In general they feast at ground level, being too heavy to reach into trees.

While the victim had a back wound that could have been caused by a bite, Dr Herbert wonders if some separate misfortune may have befallen him before the python came across what it would have seen as “a large, tasty morsel that will do me for quite a while”. Pythons can strike defensively – to lacerate and frighten danger away – or with a grab-and-hold when they intend to eat whatever they strike. They are non-venomous, yet contrary to the two-fanged caricature they have many teeth – two rows at the top and one and the bottom.

Then comes the fatal squeeze.

“They strike their prey to grab hold of it, then very quickly wrap loops around the body to hold onto that prey,” Dr Herbert says. “They’re holding on and slowly with each breath they hold tighter and tighter, so its asphyxiation that kills the prey.” A fit, strong person might be able to fight it off, but not if the python’s first strike was effective enough to establish an unbreakable hold.

Reticulated pythons are one of few snakes that grow big enough to be able to swallow a human. Once they’ve constricted their prey, their incredible jaw – which in a quirk of evolution features bones that are found in our inner ear – comes into play.

“Their jaw can open wider and doesn’t have the same hinge that we have, which allows them to eat something as big as their skin can stretch,” Dr Herbert says. Muscle power forces it down, aided by a journey through the esophagus, stomach and intestine that’s literally more straightforward than ours. They always swallow their catch head-first, which offers greater lubrication and less friction than the alternative.

While they can go six months and even a year without food, Dr Herbert points to studies showing that a malnourished python’s intestine becomes so cell-deprived as to be almost translucent, like cling film. Even a feast comes with risk. An unclothed mammal the size of a human would take a month to digest and sustain the snake for up to a year, but an inability to break down the victim’s attire would most likely have eventually killed the python even if the villagers hadn’t.

Sciences & Technology

Does a wet nose mean a healthy dog?

Dr Herbert recalls doing a necropsy on a python whose owner had fed his pet a defrosted rat placed on a remnant of an old t-shirt, only for the snake to wolf down the lot. “The python suffered from an obstruction, just the same as a Labrador does when it eats your socks. The fabric can’t be digested, doesn’t pass through, causes ulceration and infection. That may have been the outcome for this python. It may not have been a good end.”

As it surely wasn’t for the Indonesian villager. In happier news, Dr Herbert says that while Australia boasts many species of python (the largest being the carpet python of the Morelia genus), none of them grow big enough to eat a human. As for the schlock horror notion that giant snakes could get a taste for humans, that’s simply ridiculous. In captivity pythons might learn to like only the rats they are fed, but in the wild they take what they can get.

“There’s always myths and magic flying around. People are not easy prey, and they’re mostly too big for even the biggest pythons. They’re usually not slowed down or quiet enough to be easily grabbed. It’s nonsense to say pythons could develop a taste for humans. It’s just that they happen to be big enough to try if the opportunity arises.”

Banner image: Pixabay