Arts & Culture

Our savage history of fighting bushfires

A new book explores how the kangaroo became a quarry, a resource and a point of violent conflict between settlers and Australia’s Aboriginal people

Published 15 March 2020

In 1848, the Scottish explorer Thomas Mitchell wrote “fire, grass, kangaroos, and human inhabitants, seem all dependent on each other for existence in Australia; for any one of these being wanting, the others could no longer continue”.

This is a strikingly modern, ecological observation, establishing the link between humans, agency, species and the shaping of the environment that some Australians are only beginning to understand today.

The historical record tells us that colonisation in Australia was devastating for Aboriginal people. British settlers brought with them new diseases, and claimed land through violent conflict, competing with Aboriginal people for key resources. One of those resources was the kangaroo.

All kinds of native Australian species were co-opted into the machinery of colonisation, but kangaroos have a pre-eminent place here.

They soon became representative, a kind of meta-species that stood for the wonder and strangeness of all Australian native fauna – while serving the colony as a crucial resource, providing food and skins.

Arts & Culture

Our savage history of fighting bushfires

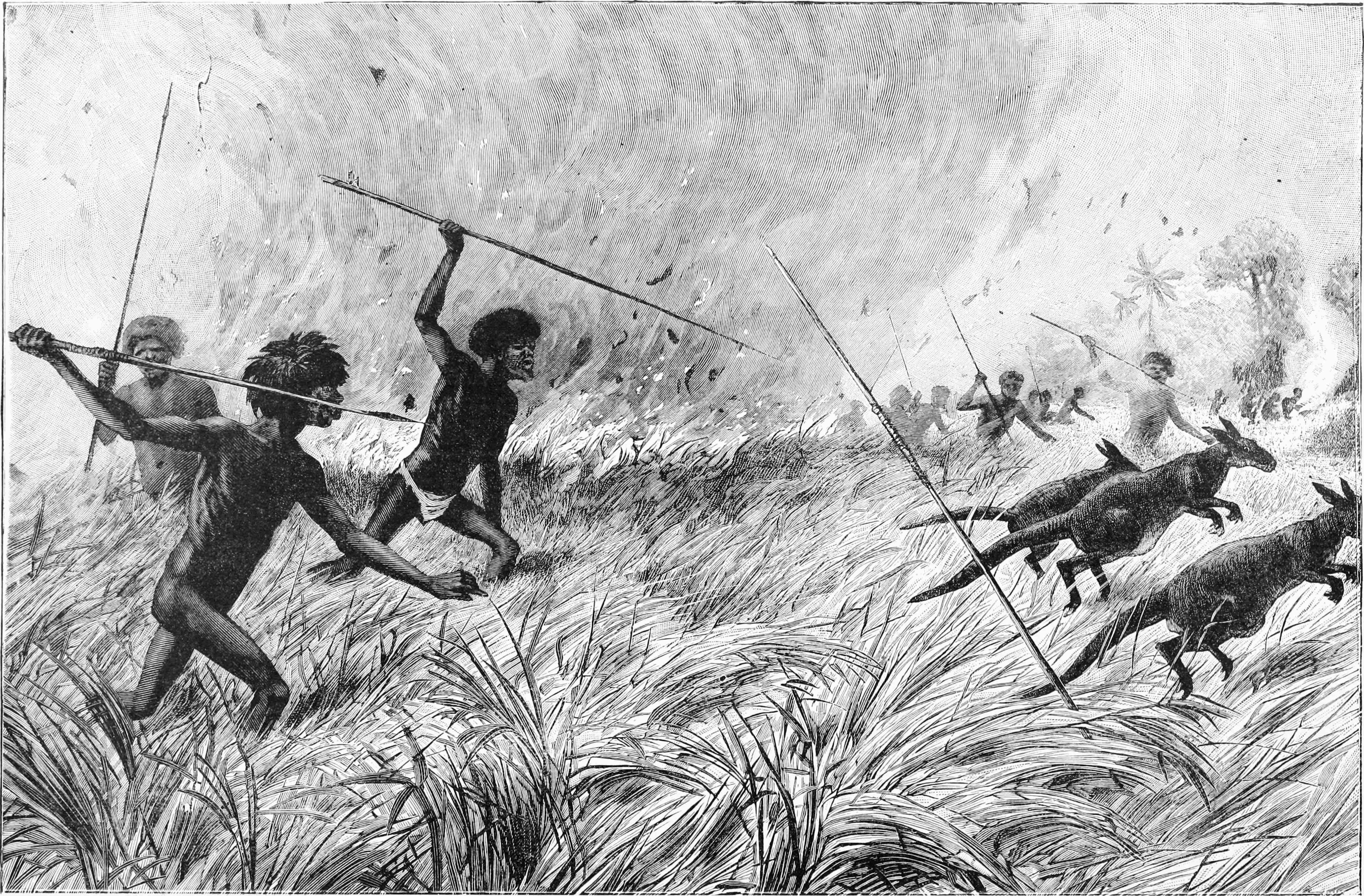

Aboriginal people had been hunting kangaroos for thousands of years, using various methods including fire or nets.

Settlers soon learned from these techniques, sometimes with the help of Aboriginal people – but often in direct competition with them.

The struggle over kangaroos as a resource led to both small and large-scale conflicts between Aboriginal people and settlers – who brought their dogs, horses and guns to the hunt.

Tasmania’s Black War, which resulted in the virtual extermination of the Aboriginal population of the island, was arguably triggered when a military garrison attacked an Aboriginal kangaroo hunting party in 1804.

The first recorded shooting of a kangaroo was in 1770, by one of Captain Cook’s officers, John Gore. And various chroniclers from the First Fleet wrote extensively about hunting kangaroos.

Watkin Tench was a young lieutenant in the Marine Corps; in his 1793 book A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, he noted the two ‘standard’ methods of killing kangaroos: “either we shot them, or hunted them with greyhounds”.

Hunting dogs soon became incredibly valuable in the colonies, trained for the purpose of killing and sold at high prices.

The influential landowner and politician William C Wentworth noted that members of the 73rd regiment in New South Wales had kept a pack of hounds for hunting between 1810 and 1814.

Health & Medicine

The birth of syphilis surveillance in Melbourne

Hunting clubs were established in New South Wales in the 1820s and, in Victoria, in the late 1830s.

Hunting for recreation was a way of consolidating settler ownership of large pastoral properties; it was a triumphant announcement of the absolute dispossession of Aboriginal people and the end of the frontier.

Networks of settlers hunted together, often turning the hunt into a festive social occasion.

In fact, the kangaroo hunt became a much sought-after colonial activity, attracting many notable visitors from overseas.

Charles Darwin joined a hunt in 1836 and was famously unsuccessful, while the English novelist Anthony Trollope fell off his horse while hunting in the early 1870s.

Hunts were often celebrated by colonial artists, too: like the sporting artist Thomas Balcombe or the English-born travel artist Edward Roper, whose 1880 painting, A Kangaroo Hunt under Mount Zero, the Grampians, shows four hunters galloping through a woodland of red gums and grass trees, chasing three kangaroos.

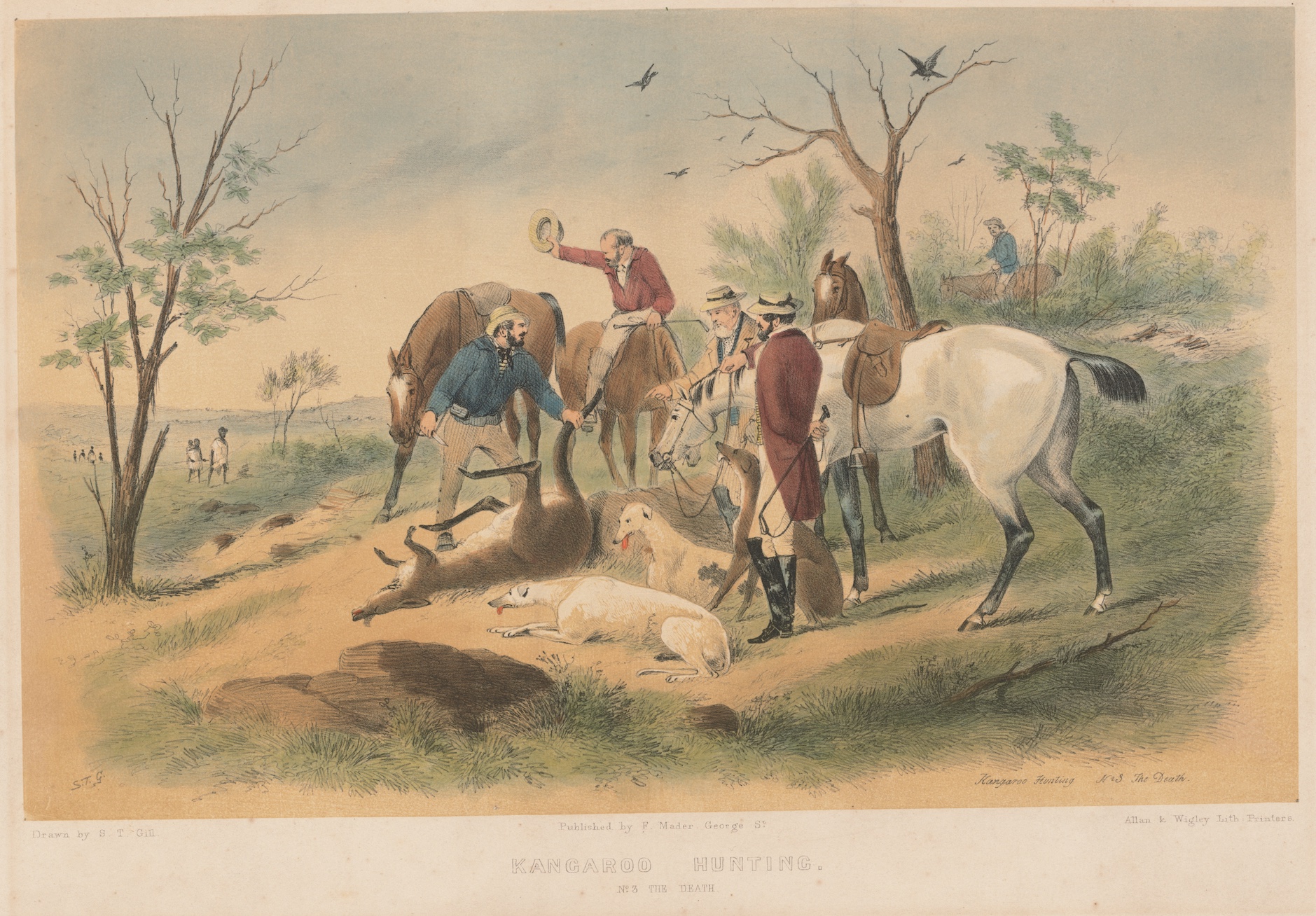

S.T. Gill is perhaps the best-known local artist to represent the colonial kangaroo hunt.

In Sydney in 1858, he produced three lithographs under the general title, Kangaroo Hunting. The first, The Meet, shows hunters and a squatter gathering together at a homestead. The Chase then puts the squatter in the foreground on a powerful white horse, his kangaroo dogs in pursuit of their quarry.

The final lithograph, The Death, shows the squatter and other hunters standing over the dead body of a kangaroo, with Aboriginal people in the distance.

This picture perhaps offers a belated recognition of the complex dynamics of colonial hunting, the question of who wins and who loses when a hunt takes place, who claims the quarry, and for what purpose.

The kangaroo hunt becomes important to colonial literature, too.

The first poem published in Australia on an Australian topic appeared in the Sydney Gazette on 16 June 1805. Titled Colonial Hunt, it presents a settler, his dog and his gun heading into the forests around Sydney to shoot a “wallaba”.

There is also a recognisable genre we can call ‘the kangaroo hunt novel’.

It begins in 1830 with Sarah Porter’s Alfred Dudley or, The Australian Settlers: the same year that the convict author Henry Savery published Quintus Servinton, generally regarded as Australia’s first novel.

Here, the kangaroo hunt is a formative experience for a young male settler, a colonial rite of passage.

The kangaroo hunt novel carried on into the 1890s, with examples like Arthur Ferres’s His First Kangaroo in 1896.

Arts & Culture

The First Fleet and Australia’s unforgiving weather

Ferres also wrote one of several kangaroo-hunt fantasies in the 1890s, which was more critical of hunters and killing.

Ferres’s His Cousin the Wallaby is sympathetic to the plight of hunted kangaroos, with a young boy who goes off to live with wallabies in an attempt to understand their embattled perspective. It’s the first Australian story to give a gun to a kangaroo, who – when hunters confront him – threatens to shoot back.

The best-known kangaroo hunt fantasy is, of course, Ethel Pedley’s Dot and the Kangaroo, published in 1899.

Here, a lost young girl is rescued by a kangaroo who has, in turn, lost her joey. Dot’s father is a kangaroo hunter; when his daughter finally returns, he renounces hunting altogether and turns his farm into a sanctuary for native species.

Dot and the Kangaroo is Australia’s first ecological fable; it wants its readers to learn about species and respect their habitat.

Its dedication – in the year before Federation – asks the ‘children of Australia’ to think differently about their relations to the non-human world, especially at a moment when native species’ “extinction, through ruthless destruction, is being surely accomplished”.

Like Thomas Mitchell’s comment about the interdependence of species in the harsh Australian environment – it’s a view that seems more prescient than ever today.

Professor Ken Gelder and Dr Rachael Weaver’s new book The Colonial Kangaroo Hunt, published by Melbourne University Press, is available now online or wherever books are sold.

Banner: A kangaroo hunt under Mount Zero, the Grampians, Victoria, Australiaby Edward Roper, 1880/ National Library of Australia