Kinecting with the orang-utans

Watch the video: Computer and gaming technology is about to let orang-utans take charge at Melbourne Zoo

Published 2 February 2016

Malu could barely contain himself. Melbourne Zoo’s twelve-year-old orang-utan was fascinated by the swishing game he was playing on a computer tablet held up by his keeper. His immensely strong fingers tapped eagerly at the screen through the wire mesh of his enclosure, but he was itching to grab it and take control himself in a move that could only have ended badly for the device.

Watching Malu was University of Melbourne Human Computer Interaction Researcher Dr Marcus Carter. “It just wasn’t how Malu wanted to interact with the tablet. He wanted to roll over it and jump around it,” Dr Carter says.

It was then Dr Carter realised the answer to giving Malu control wasn’t to make it orang-utan proof, but to use Microsoft’s Kinect 3D sensor (as used in the Xbox One gaming system) to project an interactive digital space directly onto the floor inside the orang-utan enclosure. Such a space could be activated simply by the orang-utans moving any part of their bodies across the projection.

In a world first, researchers from the University of Melbourne’s Microsoft Research Centre for Social Natural User Interfaces and Zoos Victoria are now trialling their own ‘intelligent projection’ technology to give the orang-utans control over the games and applications they play to challenge their minds.

They are now developing computer games, painting applications and picture galleries specifically designed for orang-utans. And because the researchers are using projections, the orang-utans won’t be limited to just using their fingers but will be able to use their whole bodies to activate the space. If the trial is successful, within a few years the orang-utans could be playing computer games with visitors whenever they want.

Zoos around the world, including Melbourne, have for some years been using computer tablets to enrich activities for their primates. But while Melbourne’s six orang-utans clearly love playing with and watching the tablets, there are serious limitations. In the hands of a curious orang-utan a tablet risks lasting less than a minute before being broken to pieces. It means a zookeeper has to always be holding onto the tablet from behind protective mesh.

At Zoo Atlanta in Georgia, they installed a touch screen into a tree-like structure inside the enclosure. But Zoos Victoria’s Animal Welfare Specialist Sally Sherwen wanted to go beyond that and give the orang-utans the opportunity to engage with the technology the way they want to, make it a richer experience by allowing more full body movements and also to interact directly with visitors.

She says previous research at the zoo has shown the orang-utans themselves are keen to engage. When given the opportunity to be behind a curtained off part of the enclosure or in clear view the orang-utans much preferred being in clear view.

“They enjoyed using the tablet but we wanted to give them something more, something they can use when they choose to,” Dr Sherwen says.

The goal was to ensure there was nothing the orang-utans could break or hurt themselves on.

“By having all the technology on the outside and using these emerging technologies that allow for touch detections on projected surfaces we are able to circumvent the safety issue,” Dr Carter says.

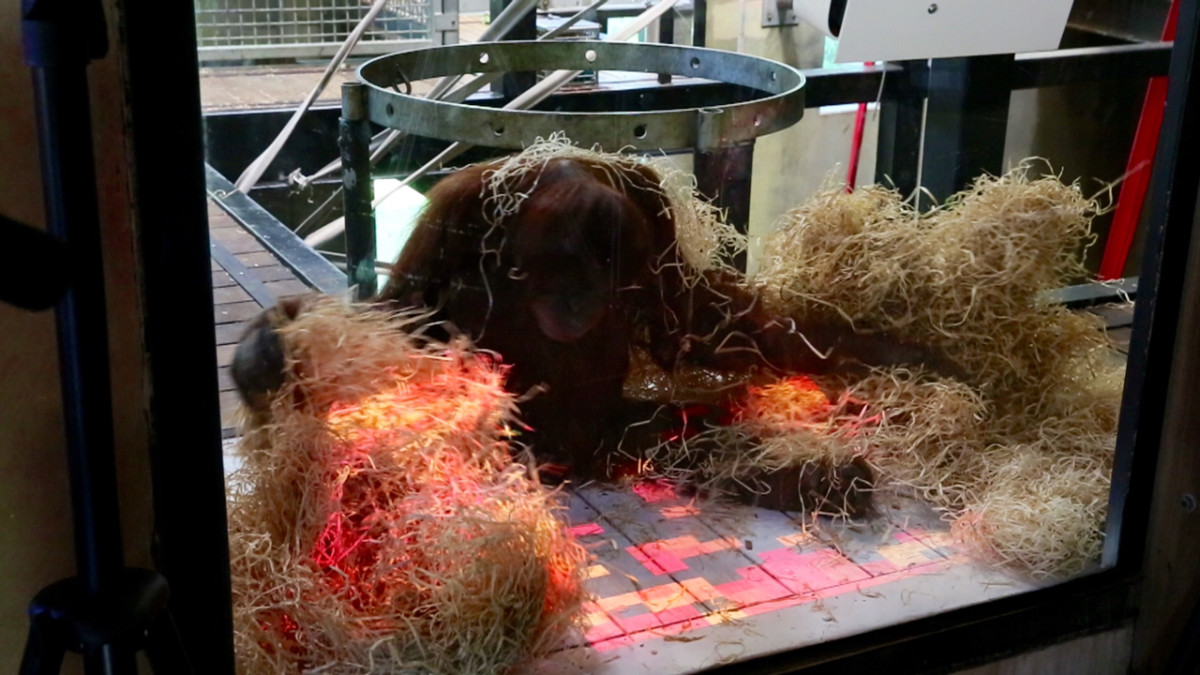

Such safety issues aren’t to be underestimated. Orang-utans are three times stronger than humans while sharing 97 per cent of our DNA. A key challenge has been projecting successfully through the three panels of bulletproof glass protecting the enclosure. But the team can now project a full body-sized screen that allows the orang-utans to ‘bodily engage’ with the projection, whether it be rolling, using it on their bodies or bringing over physical objects like leaves and bits of tarpaulin.

A game called ‘zap’

The team has developed an initial shape-recognition game dubbed ‘Zap’ that builds off a game the zoo keepers created in which the orang-utans are trained to identify a red dot on a wall to secure a treat. But in the computer game, the shape will explode with light when both the orang-utan and the human player touch the shapes at the same time. The idea is to encourage collaborative play.

More complex games are being designed, but designing for animals has presented a unique challenge for scientists accustomed to working with human subjects.

“As interactive game designers we use what we call participatory design. We work with the people who use the products and they provide input and feedback for prototypes,” says PhD candidate Sarah Webber, who is working with Dr Carter. “You can’t have those conversations with animals, so we have to find new ways to include them as participants in the design process.”

The researchers are now working with the zookeepers to tap into the different personalities of the zoo’s orang-utans. For example, females Gabby and Kiani appear to be fascinated with handbags and what people pull out of them, while male Santan is intrigued by men with ginger beards. Malu likes extracting nuts and bolts from places he shouldn’t. Indeed, Malu’s penchant for taking things apart – he managed to escape the enclosure for a short time last year – has made his keepers train him to hand over whatever bolts and nuts he extracts in return for a reward.

“These individual differences are things we can use as inspiration to design something that is complex and motivates them to solve puzzles,” Ms Webber says. “We know apes can successfully use touch screens but they are very task orientated, so we want to see if we can devise experiences that are inherently engaging to them.”

One application is being aimed especially at Kiani who loves to look at pictures of herself. Dubbed “Orangstagram”, the app allows the orang-utans to take pictures of themselves and display them. They would also be able to go through a picture library and choose what they want to look at.

Such an activity could prove to be much more than a game. It opens up the possibility of animal psychologists ‘reading’ the emotional health of orang-utans by analysing what pictures they select.

“If we design an interface they understand they could use it to communicate things about their welfare,” Dr Carter says.

Play collaboratively with visitors

Such an interface could also eventually become a shared projection space extending inside and outside the enclosure, creating a host of potential new opportunities for interaction between the orang-utans and zoo visitors. This could allow orang-utans the opportunity to play collaboratively with visitors, who can remain safely outside the enclosure. It would completely change the way animals and visitors interact at the zoo.

The researchers were excited to learn how the orang-utans would take to the projected interface, but at the first testing Malu didn’t disappoint. Spying the projected red dot moving on the floor he immediately went over to it and kissed it. The dot duly exploded and when it reappeared he kissed it again, suggesting the orang-utans are indeed keen to use more than their hands to interact.

Malu then brought over a piece of cloth and began using it to wipe at the dot. This prompted the researchers to introduce a sweeping game they had prepared where Malu used the cloth to sweep away at a matrix of red, orange and yellow rectangles that when touched gave out water ripples.

“It is really encouraging,” Dr Carter says. “We know that Malu is inquisitive but it demonstrates that even with a brand new interface he was able to get it so quickly and, after 15 minutes of use, he got better at it.”

So how far down the animal intelligence chain could this new projected interface be effective? The answer is probably much further than we think. Melbourne Zoo’s Dwarf Bearded Dragon lizards have been playing ‘Bug Crusher’ on tablets. Dr Sherwen says digital enhancement could eventually be introduced for a number of the zoo’s animals, though the opportunity to interact with visitors would always be limited to those species that want to interact.

“We don’t just want to stop here. If the trial is successful we could utilise digital enhancement to benefit a range of species, but this will be different according to a species’ preferences,” Dr Sherwen says.

It seems that one day we may well be able to turn over the zoo to the animals.

with Andi Horvath

Dr Carter, Ms Webber and Dr Sherwen have organised a workshop on the opportunities for emerging technologies in the zoo, which will bring together animal experts, zookeepers and computer scientists at the Computer Human Interaction CHI 2016 conference at San Jose in May.

Banner Image: Gabby the orang-utan exploring the new enrichment provided by University of Melbourne researchers. Picture: Zoos Victoria