Politics & Society

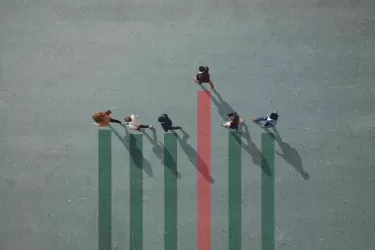

Are our new virtual workplaces equitable?

SWARM technology has brought together the country’s leading experts from Australian universities to work on our recovery after COVID-19

Published 30 April 2020

The pandemic lockdown of 2020 has changed work for many Australians. We Zoom all week without actually going anywhere, every day is a bring-your-kids-to-work day, and meetings mostly involve explaining where the mute button is.

More seriously, the changes run deep and will persist long after the lockdown.

More will be done outside the workplace and outside work hours. Work will be integrated more fluidly with family life and other activities.

When working, we will collaborate in new ways.

Our forms of interaction have always been shaped in part by the available tools, illustrated in recent decades by the rapid adoption of email, chat services, video conferencing from far-flung locations, and collaborative writing platforms like Google Docs.

Politics & Society

Are our new virtual workplaces equitable?

These changes allow us to handle familiar tasks in new ways, but they can also subtly transform the tasks themselves.

Using PowerPoint decks instead of written documents, as often happens now, affects both the form and the content of these documents, and not always for the better.

One common task for knowledge workers is rapid report-generation. A team must take stock of some situation, come to a collective position, and articulate that position, as well as the case for it, in a short report.

Think of intelligence analysts producing a report for a military commander in a tense situation, or politicians grappling with a viral pandemic.

Currently these tasks are typically achieved with a mix of methods, often including in-person white-boarding sessions and circulating Word documents by email.

However, this modus operandi is increasingly outmoded.

I’m part of the University of Melbourne’s Hunt Lab for Intelligence Research, and our researchers have been exploring new ways these teams might operate, supported by new software tools.

Politics & Society

Do we really need a tracking app and can we trust it?

We were tasked by the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA), a division of the US Office of the Director of National Intelligence, to find a way to improve the quality of analytic reasoning in intelligence reports.

Over the past three years, we have been developing and testing a new process and a cloud-based collaboration environment we call SWARM.

SWARM is defined by a unique combination of features.

One is ‘group-sourcing’, where small teams coalesce out of a larger pool of analysts, and self-organise to get the job done.

Another is the development of ‘contending analyses’ – alternative ways to think through a problem – and the subsequent selection of the most promising analysis for development into the final report.

A third feature is the use of pseudonyms to mitigate problems in group thinking arising from the different social positions of participants.

The Hunt Lab team has been testing the approach in large-scale ‘challenge’ exercises, pitting teams from major organisations with intelligence functions against large teams recruited from the public via Facebook.

These teams compete to produce the best-reasoned reports on a series of tough intelligence-type problems.

Health & Medicine

The dynamics of disease

An intriguing result emerging from these exercises is the ability of public teams to produce exceptional analysis – on average, outperforming the organisational teams.

This doesn’t mean the professionals aren’t good at what they do, but it does raise the possibility of taking advantage of the analytical power latent in the citizenry for certain kinds of real work.

The SWARM approach emerged from the intelligence domain but can be used for many other kinds of analytical work.

This was illustrated recently when the Hunt Lab was called upon to support a large and diverse ‘task force’ of academic experts in preparing a major report on Australia’s emergence from pandemic lockdown.

The Roadmap to Recovery task force was organised by the Group of Eight, that brings together Australia’s older, research-intensive universities.

It consists of around 100 academic experts from many disciplines and ranging from the most eminent professors to junior researchers who are yet to complete their PhD.

The challenge was to articulate the collective wisdom of this ‘crowd’ on a complex set of questions under conditions of great uncertainty, rapid change and very high stakes.

Politics & Society

The cost to freedom in the war against COVID-19

And unlike, say, a typical government inquiry, this had to be done in just a few weeks, punctuated by the Easter break.

In a bold experiment, the Steering Committee set aside traditional hierarchical procedures and standard tools, and instead let the whole group loose on the SWARM platform.

Experts were free to range across workspaces for each of the nine major sections of the report and contribute in whatever manner they felt appropriate.

Over a period of two weeks on SWARM, small teams emerged canvassing lots of ideas, and starting to assemble draft section reports. These drafts were then extended and polished off-platform using more standard techniques.

We observed that earlier-career and female experts ended up playing a more central role, relative to high-profile male professors, than plausibly would have been the case with orthodox methods.

The report, perhaps the most comprehensive of its kind, was publicly released on Wednesday 29th April.

This exercise was a baptism of fire for the SWARM platform, as it was deployed for the first time outside an experimental context, on the most critical question of our time.

Much was learned from the exercise, which is now informing ongoing theoretical design and technical development of the platform.

In this work, we’re pursuing the vision of legendary computer pioneer Douglas Engelbart, who once said: “The key thing about all the world’s big problems is that they have to be dealt with collectively. If we don’t get collectively smarter, we’re doomed.”

Banner: Getty Images