Politics & Society

Q&A: Recognising Australia’s first peoples ... properly

As the Government considers its response to the Uluru Statement from the Heart, we look at another major milestone in the journey towards Indigenous recognition

Published 2 June 2017

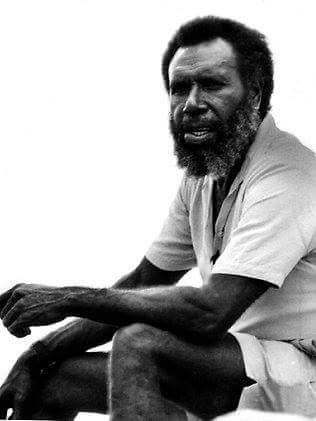

It has been 25 years since the High Court upheld the claim led by Meriam man Eddie ‘Koiki’ Mabo, along with David Passi and James Rice, that they held land rights over the Murray Islands.

The decision reworked Australia’s ‘origins story’, acknowledging the existence of Aboriginal law and custom prior to British colonisation and the establishment of the Australian nation. Symbolically and legally, it marked the ‘recognition’ of Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders’ connection to land and waters, and led to the introduction of the Native Title Act in 1993.

The Mabo decision remains an important step towards healing, says University of Melbourne Pro Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous) Professor Shaun Ewen.

“Setting right past wrongs is an important part of the healing process,” Professor Ewan says. “In a legal sense Mabo was very significant.

“Truth-telling exercises, like the Truth Commission and proportionate compensation are other important steps. Perhaps all these elements, and more, need to occur for healing to be deep and meaningful.

“Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people still face appalling outcomes in terms of our health, education and incarceration rates, to name just a few. Injustices and untruths play an insidious role in these statistics and until they are fully addressed no amount of band-aid solutions will work.

“However, Mabo was an important and foundational step towards that.”

Professor Lee Godden from the Melbourne Law School, considers the Mabo decision a significant moment in Australia’s legal history.

“It was the point when Australian law was brought into conformity with contemporary notions of justice and human rights,” Professor Godden says.

Justice Brennan, who wrote the leading judgment, held that the earlier legal position that Australia was ‘terra nullius’ could no longer be valid:

“No case can command unquestioning adherence if the rule it expresses seriously offends the values of justice and human rights (especially equality before the law) which are aspirations of the contemporary Australian legal system.”

Professor Godden says there are further challenges to ensure these “justice and human rights aspirations of the Australian legal system” are met in respect to Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders. One of the important challenges is to ensure the robustness of the Native Title system.

Having led the Australian Law Reform Commission’s review of the Native Title Act, Connection to Country, which was tabled in Federal Parliament on Mabo Day in 2015, Professor Godden steps us through some challenges.

In the decade after the Mabo decision a series of High Court decisions tested the implementation of the Native Title legislation.

“In my view this series of decisions very much narrowed the potential of Mabo and the Native Title legislation, with perhaps the best example being the central claims test – the proof that a claimant needs to bring,” says Professor Godden.

“The evidence thresholds became much more difficult to establish. A group must show they existed as a society prior to the assertion of British sovereignty and demonstrate that they have continued to practice law and custom through to the present day, and that is has been substantially uninterrupted.

“This is a huge evidentiary task and for some groups a very difficult threshold to establish.”

Politics & Society

Q&A: Recognising Australia’s first peoples ... properly

While Professor Godden says it is possible for groups forcibly moved off land to claim (where they can demonstrate they have continued to maintain spiritual connection), she believes the test works unfairly for those Indigenous peoples most adversely affected by white settlement.

“It is a sad irony that those people most affected, have the least ability to claim,” says Professor Godden.

On the one hand, the Mabo decision was vitally important as it recognised the presence of Indigenous people within Australia at the point of British colonisation – yet within the Native Yitle model the ‘recognition’ sits alongside a set of sovereign legal powers.

“This sovereign power brings with it the power to extinguish Indigenous land rights.” says Professor Godden. “Mabo affirmed these powers of extinguishment in respect of many parts of Australia, and so the ruling precluded claims where the impacts of colonisation had been perhaps the most devastating – for example in urban, east coast Australia. There remains an inequity built into the very foundations of the Mabo model.”

According to Professor Godden, the Wik decision in 1996 was the most controversial case brought under the Native Title Act, with the High Court finding that Native Title could co-exist with pastoral leases.

“This generated intense controversy,” says Professor Godden. “The Howard Government responded by legislating to greatly extend the extinguishment regime.”

The Government’s ‘ten-point plan’ and the Native Title Amendment Act 1998 saw 120 agreements and permits that had fallen into doubt because of the Wik decision reinstated.

Arts & Culture

Preserving precious Indigenous languages

Following the first decade of major High Court cases, there was a turn to stronger reliance on agreement-making under the Native Title Act. This pattern has continued to the present day and there is a growing number of Native Title determinations across the country, with many claims resolved by consent between the parties.

As Professor Godden points out, almost one third of Australia is now subject to some form of Indigenous land tenure or rights (including Native Title) or statutory land rights. Many of these areas have some form of co-existence or co-management agreement for land and waters between Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups. In this regard, Australia compares favourably with other common law countries that have Indigenous populations.

“Many of these outcomes would not have been possible without the Mabo decision,” says Professor Godden.

“However in terms of future challenges, many of the structural problems such as poor health outcomes that are evident in Indigenous communities continue in spite of the increasing pace of Native Title resolutions and agreements.

“The benefits of Native Title have been uneven across the country and it does not always deliver culturally appropriate economic benefits for the communities.

“But while the implementation of the native title system has been mixed, the legacy of Mabo remains vitally important.”

Mabo recognised the rights of Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders to their traditional lands and waters and thereby abolished the notion that, under international law, Australia was ‘terra nullius’ (the ‘land of no-one’) at the time of British colonisation.

“It was an important step for the Australian legal system but an incomplete one, as parts of our legal foundation as a nation remain tied to our colonial past,” explains Professor Godden.

“Other nations have turned to a Truth Commission or a process for dealing with past injustice and these avenues should be explored. Also, it is important to regard the platform of principles of recognition, equality and justice in Mabo as values to be affirmed in seeking to redress widespread disadvantage of Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders in our society.”

Banner image: Getty Images