Sciences & Technology

COVID-19 and Mexico’s domestic violence crisis

With almost all primary and secondary schools still closed, Mexico’s government needs to take swift action to prevent irreparable long-term damage

Published 3 August 2021

The COVID-19 pandemic has had disastrous repercussions on education in many countries. But these impacts on education have been more pronounced in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC).

The COVID-19 outbreak is projected to have long-lasting consequences for students that will significantly widen inequalities in the region and has deteriorated the continent’s development prospects.

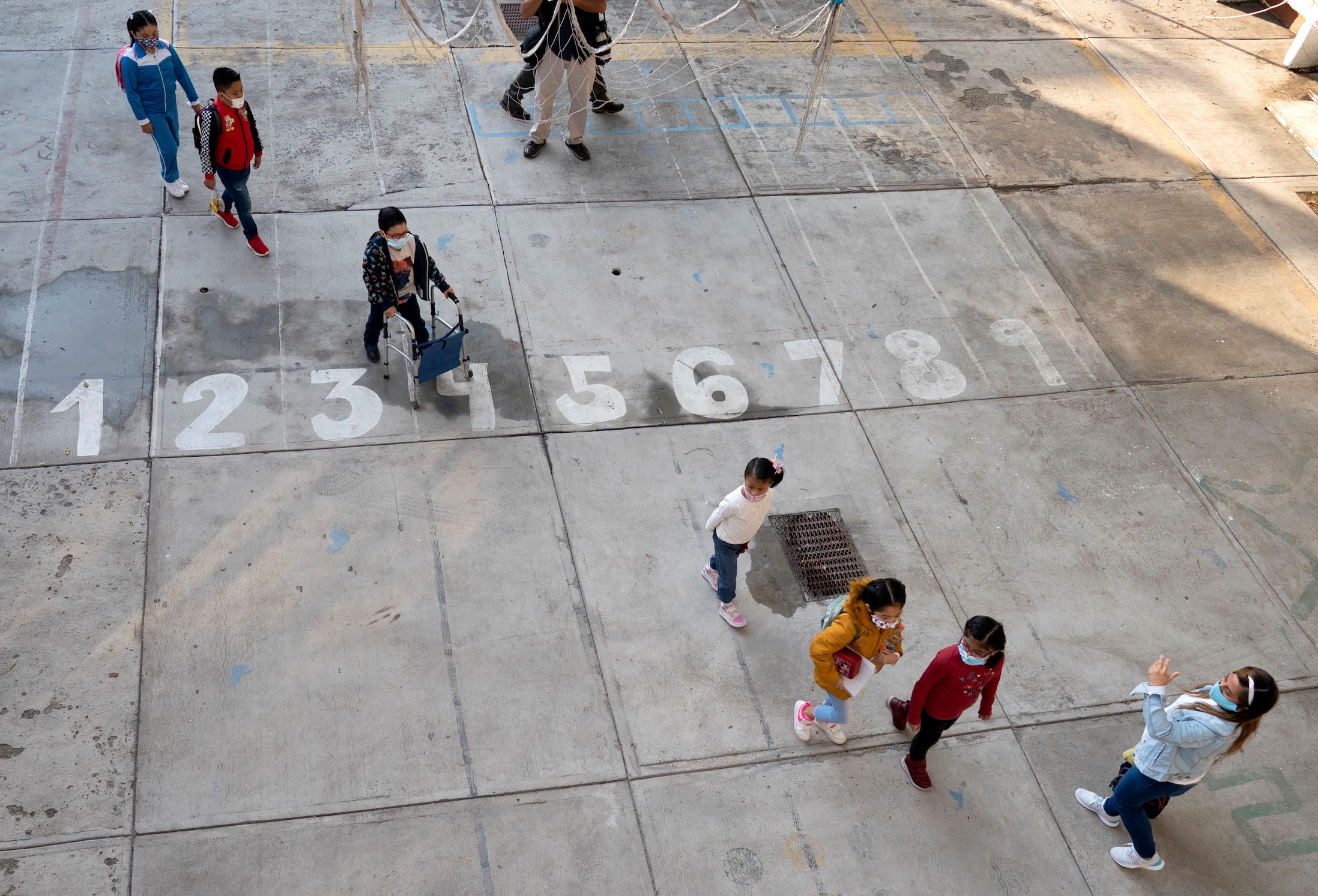

Until June of this year, 70 per cent of LAC countries were still subject to partial or total school closures, challenging children’s ability to learn and worsening their well-being. Mexico is one of these countries, with most primary and secondary schools still closed as of June 2021.

According to Forbes, in Mexico City, only 11 per cent of primary and secondary schools had reopened by June of this year.

The new academic year starts in mid-August, and more schools are set to restart face-to-face teaching. However, after more than 16 months without in-person classes, there are concerns about whether reopening can be done without significant setbacks in students’ education.

Sciences & Technology

COVID-19 and Mexico’s domestic violence crisis

For my graduate research project, I have been speaking with students, teachers, and parents across Mexico to understand how they have dealt with the disruption caused by the pandemic.

Citlalli is a 56-year-old single mother raising two teenagers – aged 13 and 16 – who are both enrolled in public schools in Mexico City.

She is worried that her children might lose an entire academic year.

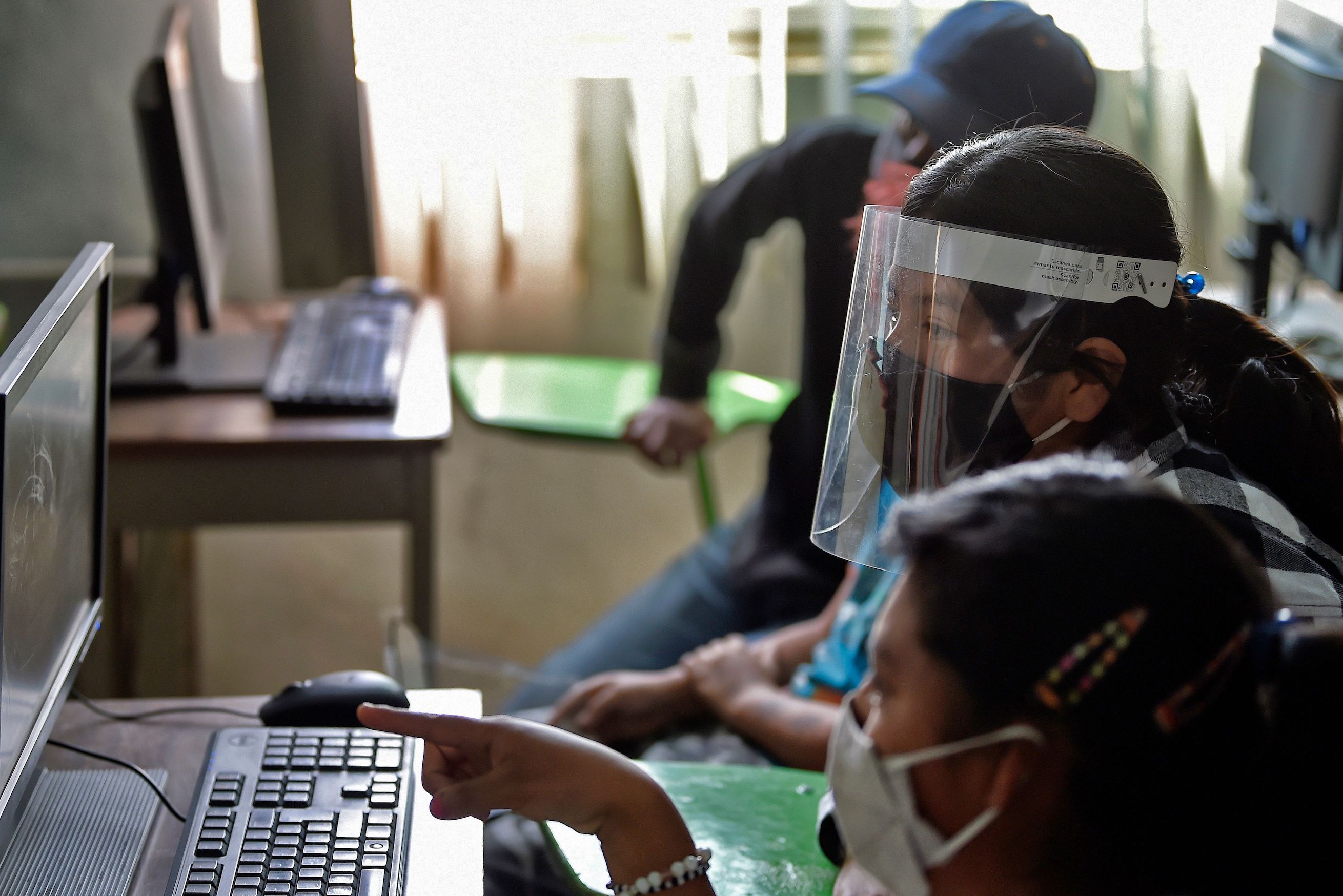

“The classes they have are once a week – for the nine subjects that both have, they only have one class a week. I think they are falling behind; it worries me. It is also complicated because we only have one tablet for both of them, and they have to take turns. I also need to supervise them, but sometimes I have to work, and I forget that they have to connect.”

Across the globe, the transition to online learning has exacerbated the digital divide, disadvantaging children who do not have access to the internet or lack devices for remote learning, hindering their academic success.

According to UNESCO, almost half of students globally have been affected by the closure of schools, with 100 million children at risk of falling below a satisfactory level of reading for their age as a result of lack of access to adequate materials.

In Mexico, lower-income groups are likely to face more significant disruption – falling further behind or even dropping out.

Politics & Society

International students enhance Australia’s universities

A survey aimed at evaluating the impact of COVID-19 on the Mexican education system shows that 5.2 million students discontinued their education during the 2020-2021 school year due to COVID-19 or lack of resources.

Even in high-income countries, like Australia, vulnerable kids are more prone to disconnect, be absent or fall behind. In the US, schools are reporting rising numbers of students failing classes, and there are increasing fears that the pandemic will erase the reduction in dropout rates seen in recent years.

With Mexico’s estimated unemployment rate of 12 per cent at the end of 2020 and with 44 per cent of those who are employed at risk of being affected by reduced hours or wages, the number of children who can afford private education in Mexico is also decreasing, placing additional stress on Mexico’s public education system.

For instance, Gilberto, a 28-year-old secondary school teacher at a private school in Mexico, is concerned that some of his students will not attend the school next year.

“In the first months, we made video classes and uploaded them to YouTube for the kids to watch. Not all parents saw this favourably and asked for a reduction in the cost of tuition. The school had to pay me less because of this; those changes have affected my economic situation a lot.

“This year, it will be even worse as some children are not coming back.”

Many children are also experiencing higher levels of stress and anxiety, making it even more difficult for them to focus on school or complete their homework.

Education

Being a teacher during COVID-19

Joabzev, 36, is the father of three children – aged five, 12 and 15. The family live in one of the most densely populated municipalities in Mexico City, Iztacalco. As a result of the pandemic and the emotional stress that his children were experiencing, which manifested as a lack of sleep and appetite, he opted to pay for teletherapy sessions for them.

“They are all in remote psychological treatment. The youngest, who is five, had episodes of great fear, a lot of anger, a lot of despair. It was hard for her to keep calm, to focus.”

Many psychologists argue that prolonged episodes of stress and anxiety might lead to depression, making these children’s mental health extremely vulnerable.

In March this year, UNICEF urged Latin-American countries to reopen schools. But there’s still no clear path to show how this will be done and how soon children can all go back to in-person learning.

The effects of COVID-19 on education may prove to be possibly irreparable. Virtual learning hasn’t been shown to be a good substitute for face-to-face learning.

Nonetheless, for governments in LAC countries, prioritising education recovery is critical to avoid further long-term severe repercussions, including deteriorated mental health, reduced future earnings and high levels of dropouts.

Banner: Getty Images