Mixing sculpture and performance in Dough Portraits

Artist Søren Dahlgaard has taken more than 2,000 “dough portraits” over seven years. Ludicrous? Yes, but closely connected to the long history of grand and serious portraiture

Published 22 January 2016

The portrait is a genre that has evolved in countless directions, taking on myriad forms in contemporary art. The staggering diversity of contemporary portraiture reflects both the wide array of creative channels available to today’s artists, as well as a new-found understanding of human identity as an ever-shifting construct.

How has portraiture changed with the advent of photography, the moving image, conceptual art and performance art? Is it even valid these days to make a distinction between portraiture and other genres of contemporary art?

The traditional function of portraits was to depict a recognisable subject and thus to declare and assert that subject’s identity and social standing. The portraitist sought not only to capture a faithful likeness, but also some ineffable element, an intimation of the subject’s deeper nature.

In the postmodern era, however, identity is understood largely as a performative construct. Selfhood is no longer perceived as something inborn, essential or unchanging. Identity is instead understood as something that is constructed in words, actions and performative rituals.

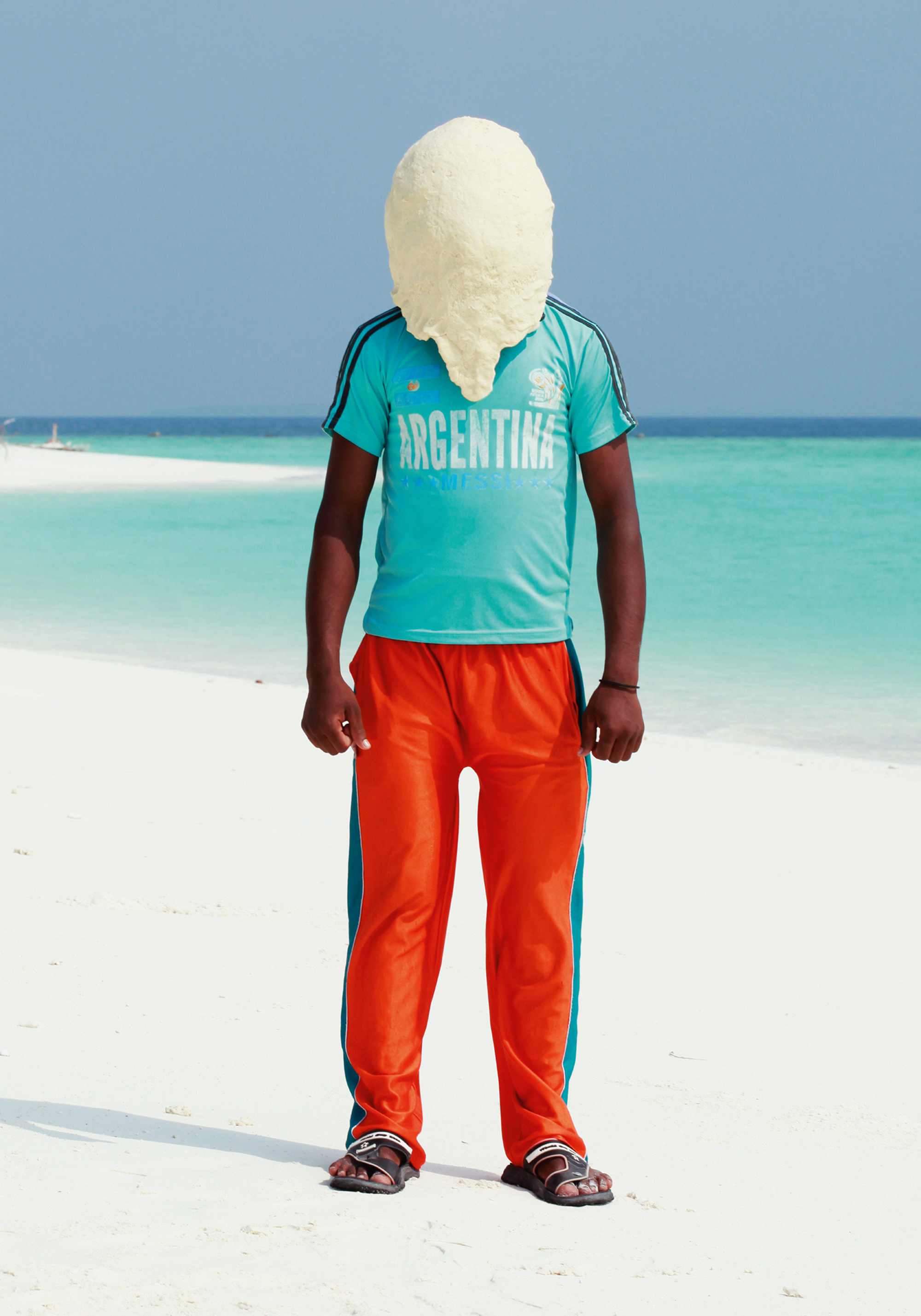

PhD candidate in visual art at the Victorian College of the Arts, at the University of Melbourne, Søren Dahlgaard’s Dough Portraits fuse together established genre traditions and portraiture as performance. Each portrait came about through active exchange between the artist and model, with the artist playing the dual roles of director and documentarist.

A heavy lump of dough weighing 7-10 kilograms was first placed on the model’s head. As the dough slowly oozed downwards, Dahlgaard fashioned it into a ‘hood’ or ‘headpiece’ that gradually swallowed up the model’s face and entire head.

The dough trickled down each model’s face in a slightly different way, providing each with a one-of-a-kind, highly sculptural new ‘face’. The artist then photographed frontal portraits of these dough-shrouded figures in their street clothes.

Dahlgaard’s portraits surprise us with their absurd humour. At first glimpse they appear to have no counterpart in any genre category. The artist nevertheless explicitly calls them ‘portraits’, inviting us to interpret them with the contextual framework of this specific genre. When asked why he chose dough as his material, the artist described dough as a living material that is familiar to everyone – and is furthermore effortless to mould.

Wearing a hood of dough is a powerful multisensory experience, revealed the comments of the models. The hood obscured their vision and muffled all sounds, enveloping them in a blanket of silence and darkness.

Contrary to conventional portraits, the models are oblivious to our gaze and reactions: they remain anonymous – they do not return our gaze. We cannot see any reactions or feelings registered on their faces.

Our attention is instead drawn elsewhere, to the hands and body language, almost as if Dahlgaard were teaching us a new language of portraiture that is indifferent to eye contact between the portraitist/viewer and the model. Instead, the encounter and exchange take place on a wholly different plane.

Dahlgaard’s portraits amusingly destabilize the conventions of the return gaze, blocking us from seeing what is conventionally regarded as the core element of any portrait: the eyes and face.

The gaze is traditionally regarded as articulating the subject’s inner essence, as encapsulated in the old saying “the eyes are the mirror of the soul”.

The absence of these familiar coordinates foregrounds the meaningfulness of other elements in the Dough Portraits. Our attention is drawn to other cultural markers such as clothing, body language and the positions of the arms and legs, while our focus remains squarely on the anonymous, living mask.

Dahlgaard subverts the traditional elements of the portrait genre – figurativeness and recognisability – by concealing the face, as if denying us access to the model’s inner being. In doing so he creates a new performative and sculptural genre of portraiture, a reinterpretation of identity – one that is funny, ironic and serious all at once.

Yet the dough portraits are much more than just portraits. They are documented performances that register emotions, actions, moments and corporeality. Under their dough hoods, the models become Other to themselves – a sculptural performance in dough, as if to suggest that selfhood and its representation is an ever-shifting process. The Dough Portraits are representations of postmodern identity.

Translation by Silja Kudel.

Dough Portraits is published by Art / Books in October 2015, www.artbookspublishing.co.uk

Banner image: Curator Majbritt Løland and Family, Randers Art Museum, Randers, Denmark, 2014