Health & Medicine

Kids’ sleep a key indicator of wellbeing

New research finds adequate sleep may minimise the impact of many childhood behaviour problems

Published 5 December 2017

Parents and carers know a sleep deprived child can be a grumpy one. But what comes first – the sleep deprivation or the bad temper, restlessness and stress-related symptoms? Does one cause the other, or the other way around? Or both?

A world-first study has tracked sleep problems in Australian children over ten years, from pre-school to high school, to better understand the relationship between a lack of sleep and a range of health and behavioural issues.

Sleep deprivation affects many families who find it difficult to achieve the Sleep Health Foundation’s recommended 10-13 hours’ sleep per night for children aged 4-5, 9-11 hours for those in primary school and 8-10 hours for teenagers.

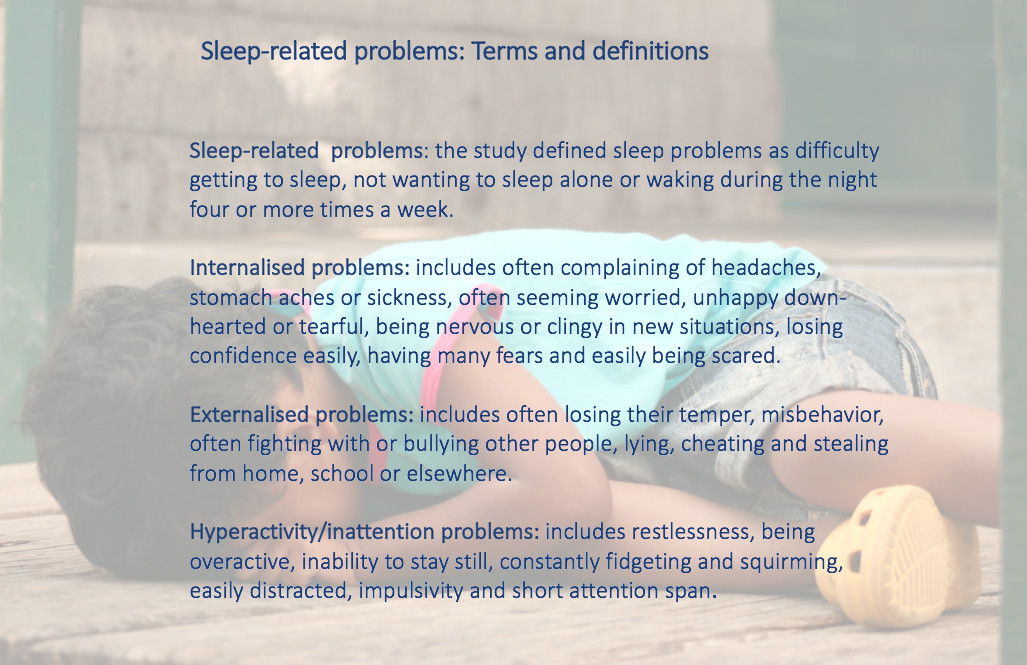

Previous Australian research has shown four in ten children experience sleep problems and one of those will be moderate or severe. Even mild cases may be linked to issues such as feeling unwell, worry, sadness, nervousness, lack of confidence, a bad temper, poor behaviour, fighting, lying, stealing and hyperactivity.

The new study, led by the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute (MCRI) and the University of Melbourne, found that inadequate sleep was associated with internalised social and emotional as well as externalised conduct and hyperactivity problems. Having these problems was also associated with a lack of sleep.

Health & Medicine

Kids’ sleep a key indicator of wellbeing

This was particularly evident as the children entered primary school.

As they grew older, the relationship between conduct and hyperactivity problems and lack of sleep remained strong both ways. But while a lack of sleep could cause social and emotional problems, having those problems did not cause older children to lose sleep.

Lead author Dr Jon Quach, from the University of Melbourne Graduate School of Education, MCRI and the Royal Children’s Hospital, says the lack of impact social or emotional problems had on sleep at an older age was surprising.

“As the children got older, the relationship seems to be more around conduct and hyperactivity problems impacting on children’s sleep,” Dr Quach says. “We thought that we would see the same effect with social and emotional problems.”

Most sleep research has investigated sleep and related behaviour at one or two points in time. This study, involving the MCRI, the University of Melbourne, The Royal Children’s Hospital, Queensland University of Technology and Deakin University, was the first to follow children at regular interviews over a long period.

Published in JAMA Pediatrics, the study used data from almost 5000 children in the first five waves of the national Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) – Kindergarten (K) Cohort. It was collected every two years when they were aged 4-5, 6-7, 8-9, 10-11 and 12-13.

The results backed previous research suggesting that sleep-related health and behavioural problems vary depending on a child’s age and are best addressed early.

“The finding of this study, along with those from earlier childhood, appear to suggest a mutually exacerbating process of early sleep problems and externalising behaviour which both contribute to later internalising problems,” the paper said.

“Interventions that are able to address sleep problems may have the dual benefit in reducing child externalising and internalising difficulties during the early years of elementary school.

“Interventions targeting externalising difficulties may also lead to benefits for children’s sleep, but the same is unlikely to be true for interventions targeting internalising difficulties.”

Sciences & Technology

What animals can tell us about sleeping

Dr Quach says the study underlines the need to establish good sleep habits from a young age, which can minimise potential health, social and behavioural problems. “Doing it earlier has potentially greater benefit,” he says. It is never too late to start, but Dr Quach says the sooner that parents and carers introduce or improve good bed time routines the better. His tips to encourage a sound night’s sleep include:

Have a set bed time and stick to it, even on weekends.

Establish a bed time routine with soothing activities in the previous hour including reading with a parent or carer.

Don’t have electronic devices or TVs on in the bedroom in the hour before bed as they can stimulate young brains. Blue light from devices such as iPads also suppresses melatonin release.

Avoid playing music on iPods or radios as they don’t generally help children to settle.

A glass of milk before bed might help.

Dr Quach, who has produced more detailed tips for raisingchildren.net.au, says the key is to encourage children to be relaxed when it’s time to settle, with as few distractions as possible.

“Our bodies will actually identify activities that mean that we’re winding down for sleep.”

Banner: Getty Images