More than a yes or no question

Changing definitions of sexual consent from just saying “no” to having to say “yes” is good but we can’t pretend that consent is just a word problem.

Published 23 March 2016

Conversations about consent need to move beyond a rehash of the 1970s’ women’s lib catchcry of “no means no”. The third-wave feminist switch to “yes means yes” however, isn’t without its own limitations.

Consent is complicated.

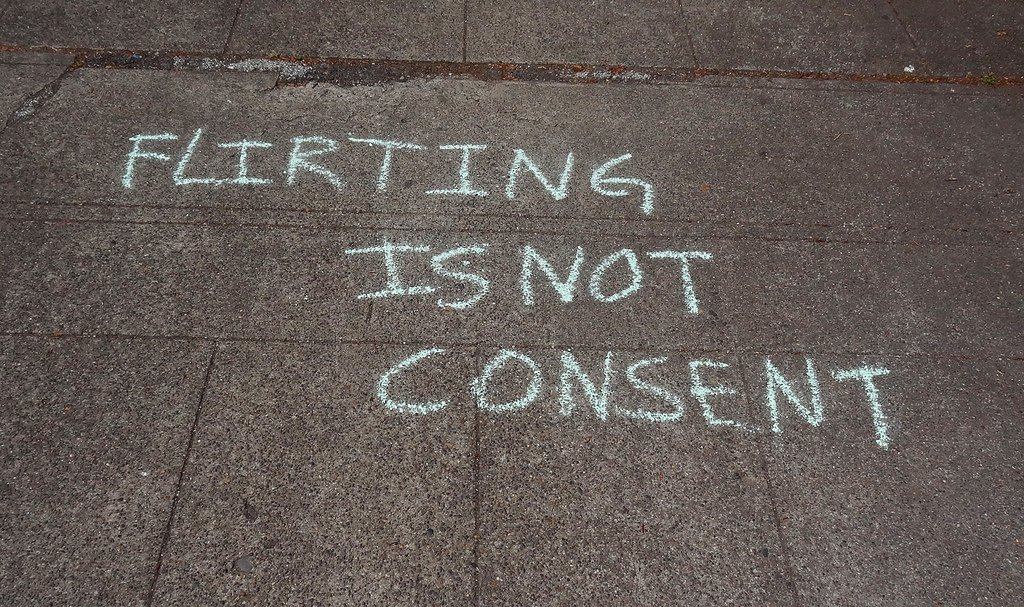

When hearts are racing, stopping to catch one’s breath and ask, “are you okay with this?” – or, God forbid, clicking the ‘Yes’ button on a consent app – is often the wrong kind of dampener. In discussing consent, we need to acknowledge the complexities of male-female relationships, of prevailing sexual norms and also question the practical application of slogans, beyond bumper-stickers and T-shirts.

The underlying principle of “no means no” is a good one. It gives gravitas to sex needing to be wanted for it to occur and for “no” to be meaningful enough to halt advances. Focusing on “no”, however, has two problematic consequences. First, what is overlooked is that “no” won’t always leave the lips of a person in an unwanted sexual situation. Second, the absence of “no” isn’t the same thing as consent.

In a culture in which women have the burden of being nice, of being acquiescent, saying “no” isn’t easy. In an intimate situation, saying “no” requires a belief that things will stop if the word gets said, that a “no” won’t get steamrolled and that no negative repercussions or challenges will follow. In a situation of assault by a stranger, saying no – saying, in fact, anything at all – may be the furthest thing from a victim’s mind. When overwhelmed, when overpowered, and when fear is potentially paralysing, saying no or debating whether a verbal protest will make a difference is likely less important than soliciting help or making an escape.

The best-case scenario is that everybody feels empowered to say “no” and that once “no” gets spoken everything unwanted stops. The problem however, is that if a word like “no” had true potency, we wouldn’t have to keep talking about consent. Events like the University of Melbourne’s Respect Week would be rendered unnecessary, and the scourge of sexual violence would be merely a talking point for historians.

The reality alas, is that we have a culture in which rape occurs – frequently — and where victims often question their complicity. Equally, we have a situation where perpetrators, sometimes even reasonably, claim they were under the impression that things were consensual because that one word they’d been taught to listen out for was left unsaid.

We need to broaden the discussion beyond a preoccupation with “no”.

First, we need to understand that “no” is only one of the ways objection gets expressed. Reluctant body language, spoken excuses, apprehensiveness and a lack of active participation are each examples.

Second, we need to force ourselves to get better at reading people. In an intimate situation, rather than assuming that everything is fine until you’re told otherwise, the focus instead should be on signs of enthusiasm. This means making sure your partner is not just going along with things, but that they actively want sex to transpire: that they are enthusiastic about it.

In the US, universities and some state governments such as California have devoted much energy to the concept of affirmative consent – to moving the discussion beyond “no means no” to a focus on both parties needing to really really want sex - that is “yes means yes”. This concept is now widely woven into violence prevention conversations and, perhaps less successfully, into the production of smartphone apps such as Good2Go and We-Consent.

“Yes means yes” however, isn’t a sexual violence panacea. The sex-positive ethos that yearns for both parties to have an amazing time under the doona is being championed within the very same culture in which strangling scripts around intercourse thrive. Despite the successes of feminism and of the sexual liberation movement, in practice, it is generally men who steer sexual proceedings and it is women who are either happily participating, putting a stop to things or, more troubling, having things done to their bodies against their desires.

A woman taking a lead role in sex and voicing her desires comes at a cost in our still-puritanical society. A woman with a vocal appetite for sex, a woman with partners aplenty on her resumé continues to be denounced as a slut. It is therefore, unsurprising that a little reluctance on her part often plays out in courtship rituals and is often not construed as dissent, but rather as an integral part of seduction, of a woman being taken.

In encouraging a woman to vocalise her “yes” and to be demonstrative of her sexual desires, we need to be mindful that society hasn’t yet embraced this.

Sex is still invariably understood as something women give to – or give up for – men; that a woman owning her horniness isn’t yet transpiring without cost.

For sex to occur, sure the absence of protest is crucial. But it’s only the start of a set of complicated conversations. No means no, absolutely. And waiting to hear that enthusiastic “yes, yes, yes” is an excellent step. But pretending such words have authority in a world of unevenly distributed power and enduring, if old-fashioned, sexual mores, isn’t helpful.

There’s much more to this conversation than yesses, nos and slogans.

Banner Image: Melvin E/Flickr