Arts & Culture

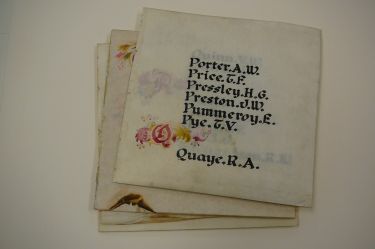

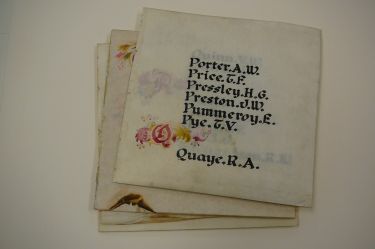

Bringing a fire damaged book back from the brink

A new book provides a timely look at the foundation myth of Gallipoli as a sacred bearer of Australian national identity, disentangling it from history, memory and forgetting

Published 23 April 2025

At the very heart of all nations are distinctive, powerful and sacred myths of origin.

Foundation myths generate potent emotional affective forces and binding collective meaning about the origin, identity and fortune of the nation and of the citizens who enact it.

All national myths – from Camelot, Alfred the Great, the Battle of Kosovo, Bar Kokhba, Joan of Arc, the Boston Tea Party, Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow, and Waterloo; to the Russian Revolution, the Battle of Britain, Dunkirk, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Long March and Gallipoli – are vigorously animated, astonishing adventures of heroic forebears in distant, golden times.

They simmer with magical wonder, raw vital enduring wisdom, and evoke deeply felt bonds of kinship, solidarity and shared meaning.

How can it be that a simple myth of nation, above all other stories, takes root so deeply that it can spur zealous citizens to sublimate personal desire, to run towards enemy fire, to face certain death, to unquestioningly sacrifice all for nation?

How can a myth of nation endure for centuries in the imagination of a people, outliving the ceaseless storms of change; the rise and fall of governments; the birth and death of technologies; wars and uprisings, prohibitions, calamities and disasters – and powerfully conjoin distant ancestors and citizens yet to be born in a grand, timeless destiny?

Arts & Culture

Bringing a fire damaged book back from the brink

Why is a myth of nation sacralised and venerated, evoking such awe that citizens are fervently moved – compelled to commemorate in solemn memory and faithful devotion, to bereave and mourn, to raise flags and lay wreaths, to contemplate fields of sacrifice, and ritually remember, honour and revere the hallowed deeds of distant kindred in the communion of the sacred nation?

The modern nation is not only a legal, political, economic and administrative system but an emotional system.

The nation is in the business of “symbolic politics”.

Belonging is a feeling as much as it is an idea. Identity is felt as much as it is understood.

Symbols, customs, rituals and cultural systems – most powerfully, national myths – act as potent distillations and performances of these feelings.

They cultivate the emotional forces of the collective so they can be channelled, coordinated and sustained even when the collective’s members are apart; and later reignited to more readily mobilise and harness national feelings of identity, affiliation and unity.

Only by recognising the unique social power of foundation myths as an elevated symbolic carrier of a nation’s fundamental values and ideologies, as an intense cultural force and template of shared belief, cohesion and continuity, can we learn from and cultivate their persistent capacity to shape group solidarity and the nation’s generational identity.

National myths don’t get in the way of the operation of the nation; they are the operation of the nation.

Why is Gallipoli still celebrated as the birthplace of the Australian nation?

Much of the discord over the puzzling status of Gallipoli stems from a failure, first, to understand social myths’ powerful symbolic role in the performance of the nation; and, second, to adequately distinguish the performance of Gallipoli as a myth from its performance in other modes of cultural discourse, such as history.

Politics & Society

Anzac Day not just for the boys

In explaining nations, much emphasis is placed on human decision-making as rational and instrumental.

Often overlooked are more ineffable, visceral factors such as emotions, which are difficult to quantify, articulate and analyse; are often positioned antithetically to the rational; and are too often dismissed as unknowable, reactive or even inferior.

The nation as a crucible of collective meaning is continually constructed from the outside by the objective force of the world and all that seems rational, and from the inside by the subjectivity of feelings and the swirling emotional force of relationships.

The sacred story that unites a nation tends not to survive its explanation.

For these reasons, mythic Gallipoli makes an unusually useful case study for demonstrating the complex operation of a foundation myth of nation.

A foundation myth of nation is an enduring, numinous, emotionally compelling symbolic story claiming historic authority which offers sacred wisdom as to the unique origin, home and kinship, and exceptional cultural, social, political and moral values, roles and meaning, of the nation and its members.

A foundation myth of nation explains the beginning, for “deep in any human community is a consciousness of its origin and its hopes and resolutions for the future”.

It locates the citizen and nation in a cohering narrative of shared place and history. It confers collective continuity.

As a story, a myth is a compelling grand narrative conforming to a plot, and familiar, usually heroic, characters and resonant tropes.

The subject matter of the mythic story invariably relates to a seminal event in a past that is remote, sometimes exotic, yet always important and traumatic, and of foundational significance to the community.

The narrative animates powerful emotions that feed and fuse feelings of reciprocity between fellow citizen and nation, building an intense emotional, psychological and moral density that yields collective attachment, solidarity, affiliation and identity.

The myth bears an elevated, often transcendent, even sacred status within the community, compelling zealous adherence, and resisting challenge or refutation.

Politics & Society

After the fighting: The soldiers who studied

A nation’s originary myth imbues the fate of people and of nation with transcendental design.

Nature is given intention and feeling, transforming the natural into the supernatural; myth animates the world through “a projection of consciousness which also clarifies consciousness”.

The myth of nation offers answers – if not rational, then emotional, psychological and spiritual – to deeper questions of significance, even cosmic importance.

In it are found cohering explanations of deeply sought, complex, often ineffable questions of origin, whether of a political, social or religious nature.

The myth brings revelation, of an apparent and important universal truth.

In so doing, the myth acts as a powerful paradigmatic framing mechanism, laden with distilled, essentialising, clarifying wisdom, which transmits to its citizens implicit values, ideals, ideologies, guidance, order; and, ultimately, meaning and significance. In a real sense, the myth reveals morality.

The questions it seeks to answer are not just existential but normative.

From the sacred wisdom illuminated by the myth, the individual and community derive a sense of faith in, and deep-seated conviction of, their individual and collective purpose, place and identity – inspiring, unifying and binding the group and the individuals within it.

They compress the past, present and future into “a fixed chain of being and becoming” in which the past leads inevitably to the future, not by chance but by destiny.

Myths bear an agentive force.

They change not only how the world is seen and interpreted but inspire a nation’s members to enact in certain ways shaped by the mythic narrative and all that is embedded within it.

The myth’s affect is profoundly performative, animating individual action, and unifying and justifying collective behaviour and governance.

The myth, like the world it explains, interprets and performs, is in a state of flux, adaptation and evolution.

Myths are mutable – always caught between remembering and erasing, between reliving and imagining.

A foundation myth makes a story, to make a nation, to make meaning.

Nations, national identity and those who forge them are driven as much by powerful subjective, often irrational, desires, feelings and emotions, which fuel a primal hunger for unity of kinship, homeland, belonging and the sacred, as much as by any rational conception of social organisation; and it is in the most vital and ancient form of discourse, the myths and stories that nations and citizens tell about themselves, that these emotions are distilled and harnessed in a potent, symbolic, sacred and always evolving performance of belonging.

This is an edited extract of the new book Nation, Memory, Myth by Steve Vizard, published by Melbourne University Publishing, and released on 16 April 2025.