Environment

The future of our cities is Indigenous

Due to longstanding ethnic and political divisions, New Caledonia is caught in a new round of geopolitics and its referendum outcome is unlikely to please everyone

Published 10 December 2021

There are three French territories in the Pacific that are not ‘decolonised’.

The one closest to Australia, New Caledonia (Nouvelle-Calédonie or Kanaky, as Indigenous inhabitants prefer), is set to hold a final referendum on independence from France on 12 December 2021.

The process of decolonisation has been slow, and complex: French authorities committed to partial self-governance for the territory decades ago, but with a maximum of three referenda to be held on full political independence.

The 2021 date has become a flashpoint, since this important event coincides with the effects of a COVID outbreak that began in September 2021.

Environment

The future of our cities is Indigenous

Indigenous Kanak political leaders argue that the rights and customs of their communities are not being respected as deaths have risen and extended periods of customary mourning will hinder voting for thousands of people.

They are calling for non-participation in the referendum.

This French-speaking territory has a strong mining economy, with around a quarter of the world’s nickel reserves. Around 40 per cent of the total population are Indigenous Kanaks with Melanesian origins dating back over 3,000 years.

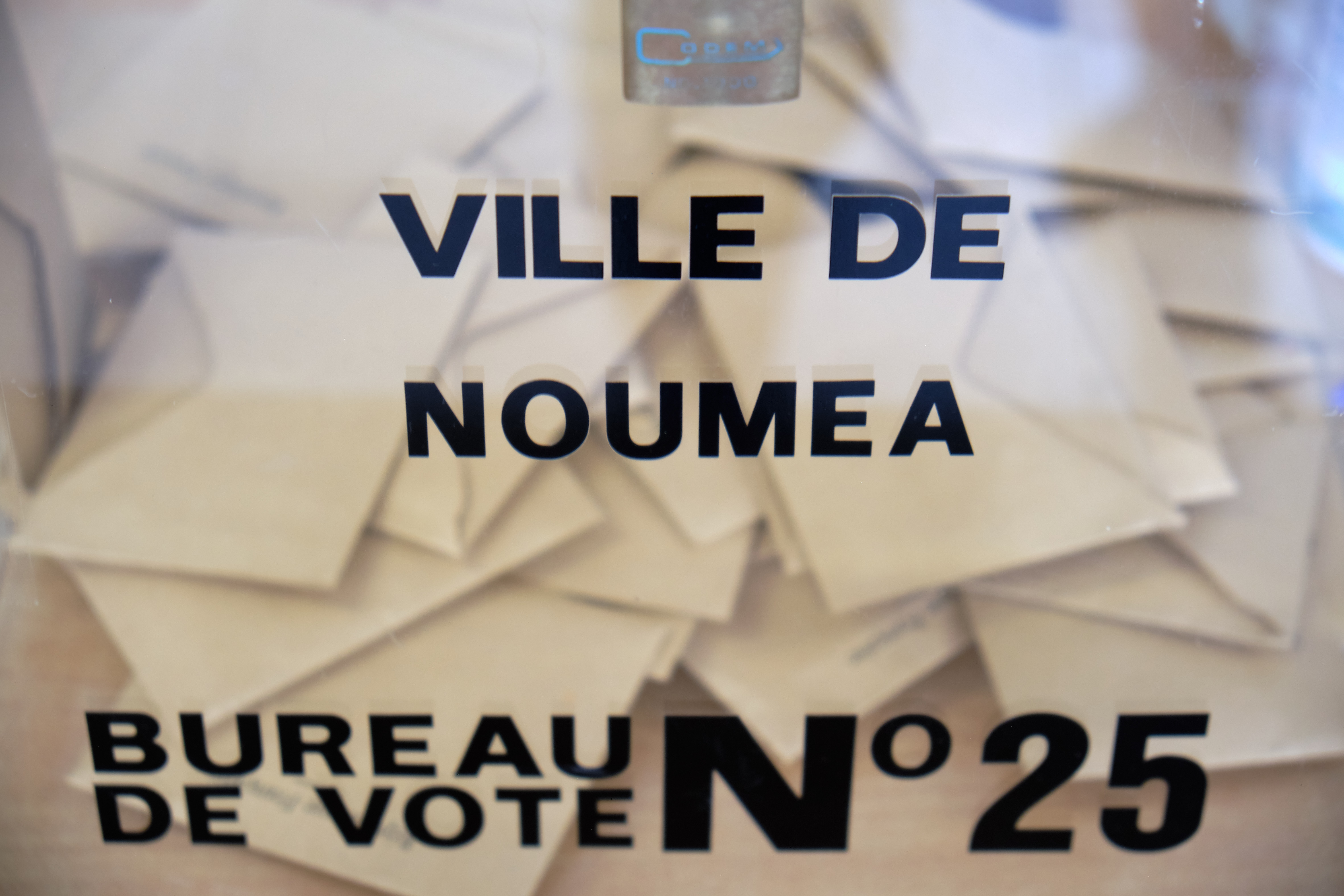

Many pro-France supporters are migrants or have ‘settler’ origins, and are most numerous in the Nouméa urban area, the ‘Paris of the Pacific’ in the south of the main island Grande Terre, which is home to over half the population of 271,000.

The territory enjoys strong links with and financial transfers from France, around $AU2.45 billion in 2018 (17 per cent of GDP). President Macron has promised to retain this support if the ‘no’ vote prevails.

Pro-independence supporters are mostly Kanak, but include some inhabitants with Pacific, European or Asian heritage. They cite historic racism, ongoing discrimination and economic disadvantage.

The Matignon Accords were brokered in 1988 by Jean Marie Tjibaou, a charismatic Kanak leader who fought for an end to the marginalisation of Kanak culture by French colonial society. France wanted to calm separatist aspirations after a civil war between 1984 and 1989, euphemistically called the événements (events) in which 200 people died.

Politics & Society

Submarines and vaccines: France’s 2022 presidential elections

The extensive archipelago was divided into three provinces – two strongly dominated by Kanak representatives. Provincial governments now control most of their own affairs and budgets.

In the North Province, the Kanak majority leadership has managed to negotiate the largest Indigenous controlled mine and processing plant in the world with majority ownership through its Société Minière du Sud Pacifique (SMSP) of the massive Koniambo nickel deposit, in partnership with the Anglo-Swiss mining company, Glencore.

It provides jobs, subcontracting and other opportunities to local communities, overwhelmingly Kanak – more than 90 per cent of Koniambo employees are local. As an economic anchor, it is still a risky venture, suffering economic ups and downs.

French authorities cite provincialisation as a solution to New Caledonian citizens ‘living better together’, with French citizenship but without political independence.

However, the reality is that a distant European power still controls law enforcement, the university, currency and foreign affairs. The contrast with Pacific neighbours like Vanuatu is striking.

France has chosen December 12 as the date for the last referendum unilaterally, without full consultation. France’s former Prime Minister Edouard Philippe had promised that it would not take place between September 2021 and April 2022, to avoid it being a political football prior to the French Presidential elections which begin on April 10, 2022.

Environment

Building collective knowledge for action

However, the French Council of Ministers, including Sebastien Lecornu, the French Minister of the Overseas and the current Prime Minister Jean Castex, announced the referendum date back in June 2021.

The French government has taken a clear position against political independence while officially neutral – in an August speech in Tahiti, President Macron said that France would be “less beautiful” without New Caledonia.

The previous referenda in 2018 and 2020 have shown that the territory is strongly divided.

In 2020, only 53.26 per cent voted to remain with France. The independence movement hoped that they could swing the vote this time.

The FLNKS (National Kanak and Socialist Liberation Front) have asked for a postponement and were refused. With more than 270 COVID deaths since September, going to the ballot boxes or running an election campaign will be difficult for those in mourning.

The calls to shift the date have been supported worldwide.

Some 64 academics from France, Australia and other countries have published an open letter in French newspaper Le Monde: France must respect the rights to self-determination for colonised people. What value will a vote have next week without full participation, and might it turn violent?

Dr Denise Fisher, former Nouméa-based Australian Consul-General, has declared any vote in which sectors of Kanak do not participate to be “inconsistent with France’s commitment under the Noumea Accord to recognise the identity and customary institutions of Indigenous people”. She said this demonstrates “France’s apparent disregard for Kanak custom”. France has sent 2,000 police to “secure” the vote.

Sciences & Technology

Leaving no one behind

Geopolitically, the archipelago not only has nickel, but a vast Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) bordering Australian waters and with unknown seabed and hydrocarbon resources. This gives France military, political and economic influence in the Pacific at a time when China is investing heavily and trading with neighbouring countries.

We predict that if the referendum goes ahead, France will cement its position as a Pacific European power. But the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonisation may question the vote’s credibility, and political and legal battles could persist for years.

Kanak political leaders say that, if the vote is ‘yes’, they will still retain strong links with France. FLNKS representative Rock Wamytan, president of the New Caledonian parliament, declared that he is in favour of an associated state. They are not keen on extending links to China, whose power is growing in the Pacific.

This small territory, with its longstanding ethnic and political divisions, is suddenly caught up in a new round of wider geopolitics.

Macron opposes independence and can attract some right-wing voters in France if the referendum goes his way. An outcome pleasing everybody is impossible: historical justice is unlikely.

Both authors signed the petition in Le Monde and are editors of The Geography of New Caledonia-Kanaky (Springer, 2022).

Banner: Getty Images