Obesity link to packaging chemical

New research brings scientists a step closer to understanding how exposure of embryos to BPA, a common chemical found in plastics, could impact our health

Published 14 July 2016

Today, you might buy a takeaway coffee on the way to work, eat a home-made salad for lunch with a tin of tuna and pocket the receipt after your weekly supermarket shop on the way home.

But inside that cup, tin and receipt is Bisphenol A (BPA), a common chemical in plastic food and drink containers, and used as a barrier between food and aluminium in a variety of tinned food and soft drink cans.

Studies show traces of BPA can be found in more than 95 per cent of the human population. There has long been debate about the safety of BPA, because its chemical structure is similar to the human sex hormone oestrogen with which it can interfere. BPA exposure has been linked to obesity, behavioural problems, asthma and even cancer, but most public health agencies worldwide consider it to be completely safe.

Now, University of Melbourne researchers have identified a possible mechanism for the link between BPA and obesity, casting fresh doubt on its safety.

The research, published in the Nature journal Scientific Reports, suggests that even short-term exposure of embryos to environmental levels of BPA in the first days of pregnancy, significantly reduces the number of embryos that develop and, notably, alters their metabolism.

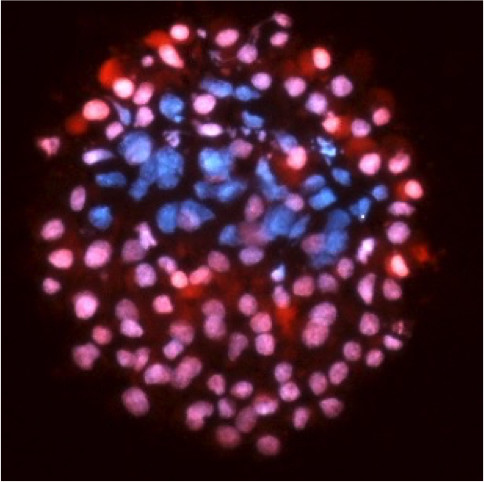

In the ground-breaking study using cattle embryos, the researchers showed BPA exposure led to a substantial rise in the embryo’s consumption of glucose, its main nutrient, highlighting a potential mechanism to explain the link between BPA and obesity.

“As a population, we’re getting more and more obese and not all of it is because of diet and lack of exercise,” says Dr Mark Green, from the School of BioSciences, who headed the study. “There are likely to be other factors, and this research suggests this could include exposure to endocrine disruptors such as BPA.”

Voluntary phase-out

Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) states there are no health concerns with current levels of BPA in food and drink packaging. But worldwide, including in the European Union, Canada and several US states, BPA use is being phased out in some products.

In Australia, FSANZ introduced a voluntary phase-out of the use of BPA in plastic baby bottles in 2010. In most cases, the health agencies state that the phase-out is because of consumer demand rather than specific evidence of harm.

Dr Green and his fellow researchers – Dr Alexandra Harvey and MSc student Bom-le Choi – exposed 4,215 cattle embryos to the chemical for four days at concentrations that have been found in humans.

The embryos were then studied until day seven of development.

Some 47 per cent of the embryos in the control group made it to the correct developmental stage by day seven, compared to 40 per cent that were exposed to BPA.

But it wasn’t just an issue of whether either group of embryos developed or not. Dr Green says embryo quality was also examined, and the BPA group did “far worse”.

“On top of the development difference, of the BPA exposed embryos that did develop, there was a 10 per cent decrease in good quality embryos compared to the control embryos,’’ Dr Green says. “So by combining the reduction in successfully developing embryos with the drop in good quality embryos, the effect is more like a 17 per cent difference between the groups in terms of good quality embryos that had developed on time.”

The most notable finding of the study however was that the BPA-exposed embryos that did continue to develop had an altered metabolism. Over the last 20 years, an increasing body of research has shown changes in the early embryo can affect a person’s health in later in life.

Short-term exposure

Dr Green says the research suggests even short-term exposure to environmental levels of BPA can potentially have a long-term effect on people.

“There have been a number of epidemiological studies that have identified an association between BPA and obesity in humans, but the mechanism and the timing of when during development and how this occurs was unclear,” he says.

“Now we can see that exposure to BPA levels found in the human population can increase glucose consumption in the embryo. This might well result in obesity in later life.”

Dr Green stresses that establishing the link between BPA and obesity needs further examination, but this study will likely encourage greater research in this area.

The idea is that BPA, by mimicking oestrogen, could change how people metabolise food, leading to weight gain.

Dr Green says because BPA is found in so many items – almost all people in developed countries have measurable levels of the chemical in their systems – even if they use a BPA-free drinking bottle.

Adverse health impacts of BPA were first raised in the early 1990s. To date, BPA – one of the highest quantity human-made chemicals in the world – is also one of the most studied endocrine disruptors in the world.

Dr Green hopes further BPA research will specifically focus around the critical time of conception and early embryo development.

“Future studies could extend the amount of time the cattle embryos are exposed to BPA and then we could transfer those embryos into surrogates to see what happens to the offspring, in terms of their development and metabolism,” he says.

“The findings of this research may seem alarming but it’s important to remember that this study was done in vitro. Whereas in the body, BPA is ingested with food and drinks that may bind it, also the body has the ability to block, breakdown and excrete BPA relatively quickly that means its potential effects are likely reduced.”

In the meantime, there have been efforts to reduce people’s exposure to BPA. The consumer-led push to get manufacturers to go BPA-free forced them to embrace of alternatives such as Bisphenol S and Bisphenol F – both chemicals that studies show impact human hormones in a similar way.

So what can people do to reduce their exposure to BPA and other similar chemicals?

“In the world we live in, there’s no way of avoiding exposure to endocrine disruptors like BPA,” says Dr Green. “But if you want to minimise exposure to endocrine disruptors, you can definitely do many simple things such as wash your fruit and veg, don’t heat food in plastic containers, don’t drink hot liquids out of plastic containers, and drink water from glass or metal bottles; don’t use squeeze bottles.”

Banner Image: Rakesh Rayapaati/Flickr