One of the most affecting and unsettling things I have ever seen

The Berry Collection was a poorly curated anatomical and anthropological collection that facilitated scientific racism and was dominated by unethically sourced Aboriginal remains

Published 28 May 2024

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains images and names of people who have died. It also includes distressing descriptions and derogatory terms for Indigenous people used in their historical context.

It is difficult to convey to a modern audience how commonplace and necessary collections of human remains – particularly non-European human remains – were considered to be in nineteenth and twentieth-century museum culture.

In a paper from 1908, German anatomist Hermann Klaatsch succinctly captured the zeitgeist: “Man – not only his head, but every part of his skeleton, body and limbs – has now become an object of natural history to be studied like any other animal.”

Well into the twentieth century, the University’s Anatomy Department boasted of possessing “a collection of aboriginal [sic] skeletal material which ranks among the best in the world”.

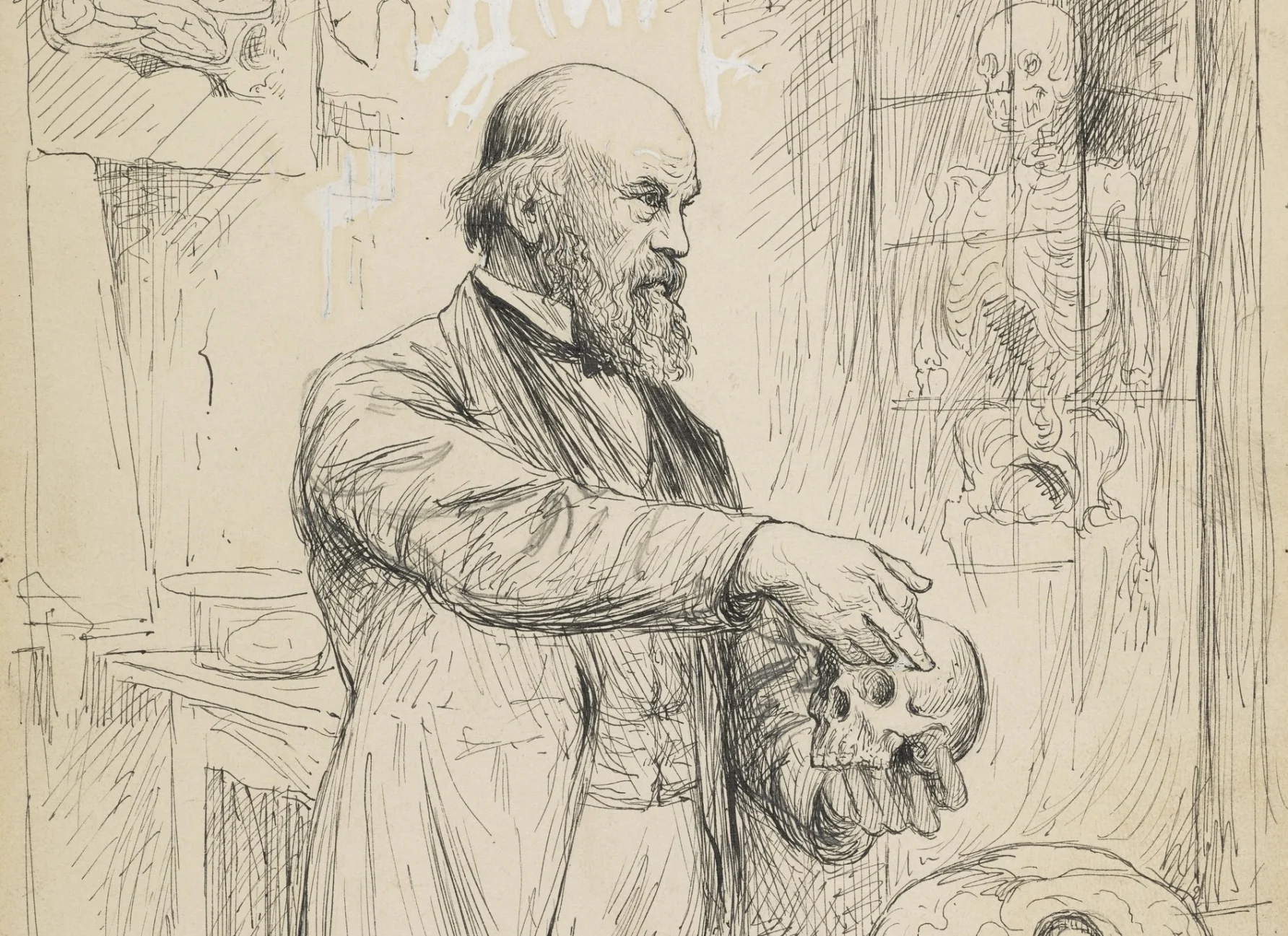

The collecting of Aboriginal human remains at the University began with George Britton Halford, the foundation professor of anatomy, physiology and pathology.

During his lifetime, the anatomy of Indigenous skulls was often listed as one area of Halford’s expertise; however, he managed only a single publication in this field.

In 1878, he produced a craniological study of Victorian Aboriginal skulls as part of Australian civil servant Robert Brough Smyth’s two-volume work The Aborigines of Victoria.

Halford had collected at least eleven Victorian Aboriginal skulls for this study and sawed five of them in half to inspect the internal topography.

One of the skulls was taken from Bunurong man, Jimmy Dunbar.

Dunbar was well known to the Mordialloc community, working for a time as a mounted trooper, and was remembered as wise, dry and amusing. He died in Alfred Hospital in April 1877, six days after the death of his partner.

Halford wrote that Dunbar’s skull “was obtained through the kindness of Dr. Cooke”, the Alfred’s resident medical officer and honorary surgeon, and a student, future University of Melbourne chancellor, Anthony Brownless.

It is striking to a modern museum worker that little to no detail is provided for the Aboriginal skulls used in the study.

Apart from Dunbar’s remains, and one skull described as “probably female”, there are no descriptions or information about the individuals’ geographic origin, age, pathologies or any other context whatsoever.

More than one contemporary reviewer of Brough Smyth’s book pointedly noted that Halford’s contribution consisted merely of measurements of several skulls without providing a word of further explanation.

It is the earliest example of a recurring theme: a tacit presumption that holding large collections of Aboriginal bodies is justified in the name of scientific knowledge – but the science was never very good.

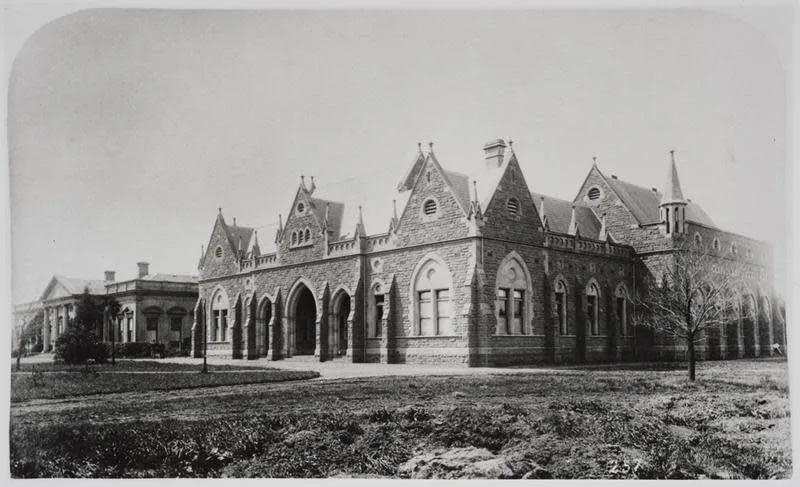

Professor Richard Berry arrived in Melbourne in 1906 and, with great zeal, he rapidly supplemented the old anatomy specimens with frozen-tissue sections, potted dissections, and so many anthropological specimens and casts that they appeared to form the basis of a dedicated department.

At the end of his reign, Berry considered the departmental collection he had assembled a museum of anthropology as well as anatomy.

Berry’s anthropological claims rested on the ‘bioanthropological’ skull collection.

Bioanthropological collections were assembled in numerous museums and university departments during this era as a response to scientific interest in phrenology, race science and eugenics.

These collections comprised an inventory of human remains – primarily skulls – from different ethnic communities sourced from all over the world

In 2019, I visited the archetype of bioanthropological collections at the University of Edinburgh, Berry’s alma mater.

Established by anatomist Sir William Turner in the nineteenth century and preserved in its original state, the collection is housed in a purpose-built, two-tiered, wood-panelled room containing hundreds of individuals reduced to skulls and arranged by ‘race’.

It is one of the most affecting and unsettling things I have ever seen.

The Berry Collection was Berry’s attempt at creating a Southern Hemisphere replica at the University of Melbourne.

If a catalogue of the Berry Collection was produced during Berry’s era, it has neither been unearthed nor referred to in any publications.

According to departmental lore, the custodian of the Berry Collection in later years, Professor Kenneth Russell, is said to have responded to this deficiency with the retort, “Who needs a catalogue? Berry knew what was in the collection and so do I.”

A list of the remains comprising the Berry Collection compiled in 1987, before any repatriations were made, documented more than 700 human skeletal remains. Prior to their return, Indigenous skulls and mandibles made up three-quarters of the collection.

Over sixty remains of juveniles and infants were represented, including at least four skeletons of Australian Indigenous children.

Even at the time, Berry was criticised for substandard research methodology.

In 1927, English biometric anthropologist Geoffrey Morant described some of Berry’s measurements of Tasmanian Aboriginal skulls as “insufficiently defined” and others as “obviously incorrect”.

Twelve years later, Melbourne Museum craniologist Dr James Wunderly backed up Morant’s critique and spent a further five paragraphs pointing out inadequacies in Berry’s anatomical work.

Health & Medicine

This has so rarely occurred in the University’s history

This weak science can often be traced to Berry’s deeply entrenched biases and assumptions. He had an unquestioning adherence to physiologically based hierarchies of race and class that was totally unscientific.

The Berry Collection should have been handed over to Museums Victoria in the early 1980s when another University collection, the Murray Black remains, were, but it remained at the University for a further two decades.

In September 2002, long after the old-school anatomists had died or retired, the collection was uncovered in a locked storeroom and proved an embarrassing reminder of the University’s past practices.

Although described as a rediscovery, the continued presence of the Berry Collection was an open secret with the Anatomy Department.

This time, all the remains of Indigenous Australians from the collection were organised and sent to the Melbourne Museum for repatriation.

The University apologised for the “hurt and understandable indignation felt by Indigenous Australians” and paid $AU172,000 towards the cost of repatriation and reburial of the remains.

The non-Australian remains of the Berry Collection are still held by the Harry Brookes Museum of Anatomy and Pathology.

This is an edited extract from Dhoombak Goobgoowana – A history of Indigenous Australia and the University of Melbourne – Volume 1: Truth, published by Melbourne University Publishing and edited by Dr Ross Jones, Dr James Waghorne and Professor Marcia Langton. Hard copies are available to purchase, and a free digital copy is available through an open-access portal.