Our business leaders must think critically

Critical thinking has become highly valued in business, but these skills aren’t taught to business students. So, how do we ensure that the next generation of business leaders don’t repeat the mistakes of the past?

Published 18 February 2020

Business scandals have existed for almost as long as the idea of ‘business’ has been around.

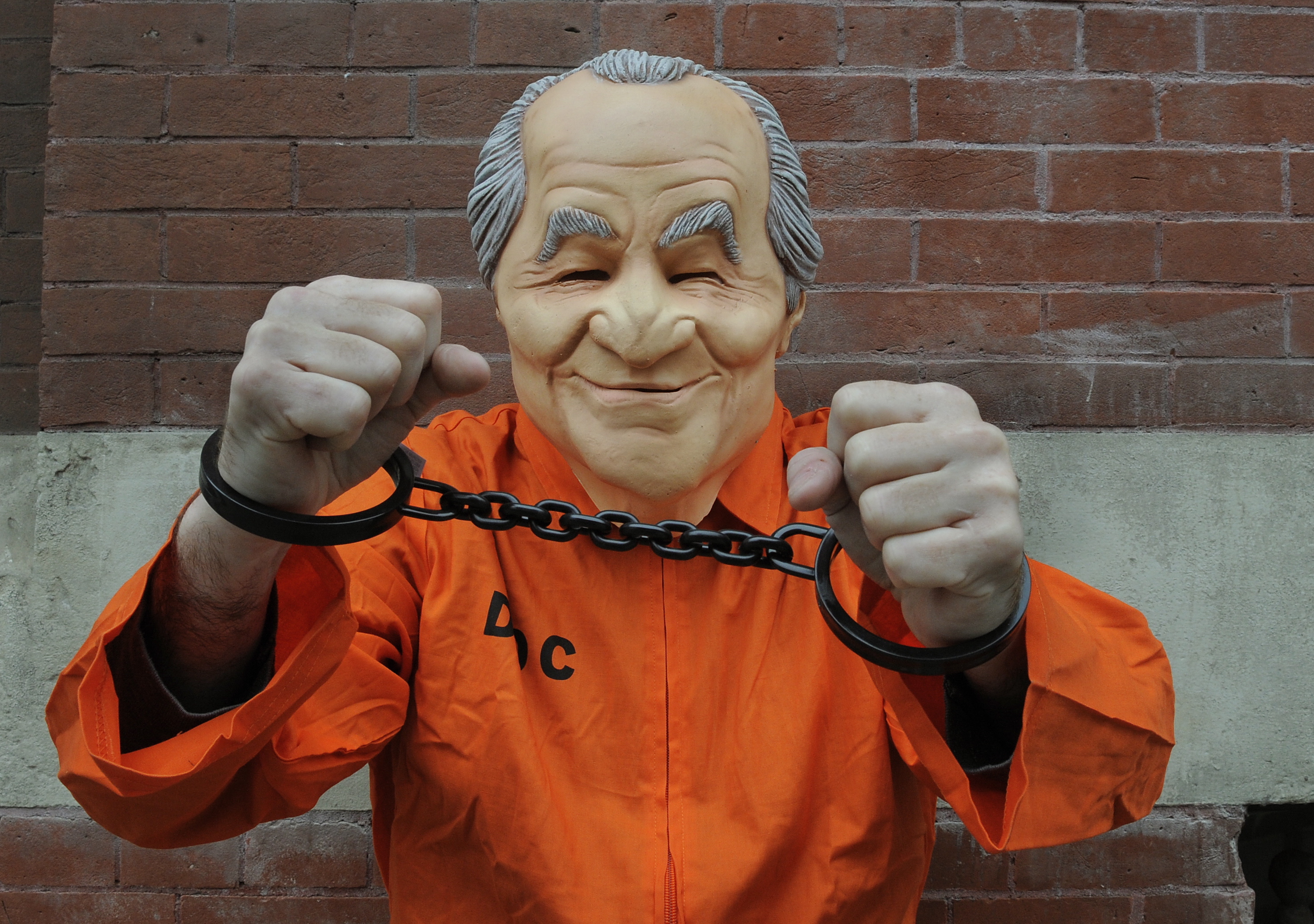

Many of us may be aware of Australia’s recent Royal Commission into misconduct in the financial sector, as well as the US subprime mortgage scandal that sparked the Global Financial Crisis, and even jailed financier Bernie Madoff’s $US68.8 billion Ponzi scheme.

But back in 1494, the Medici Bank, once the largest banking conglomerate in Europe, collapsed after profligate spending. The issue of ethical behaviour in business clearly has a long history.

Given this history, it’s not hard to understand why banks and other large corporations are viewed with suspicion, and why a customer preference for ethical (socially responsible) businesses is on the rise.

One way to understand the failure of some of these corporations is that business leaders are failing to think critically about their core responsibility as good corporate citizens.

But what does it mean exactly for a business leader to “think critically”?

Critical thinking is particularly vital to business.

It helps health care professionals make important decisions that saves lives and the same thinking assists lawyers to make decisions in the interests of their clients.

In business, critical thinking helps business practitioners make strategic investment decisions for optimising clients’ returns in an ethical and socially responsible way.

A lack of critical thinking in business has real implications on real people.

If the running of Australia’s financial services industry had been properly informed by and practised the requisite skills and dispositions of a critical thinker then there would have been no need for a Royal Commission.

Without the vast public funds it cost, not to mention the endless stakeholder misery that would have been avoided in the first place.

But how do we ensure this? It surely starts with business education.

Teaching critical thinking for business

Unfortunately, despite the importance of training future business leaders in critical thinking, business education lacks universally agreed-upon ways to teach it.

Indeed, it’s seldom taught explicitly, despite promising new ways on offer.

In fact, “critical thinking” is rarely — if at all — given prominence in the curriculum within business schools as a subject worthy of independent study.

Graduate attribute boxes are checked, and students are assumed to have absorbed – by osmosis somehow – skills in critical thinking through studying economics, accounting, finance and management.

But there is evidence to suggest that, without explicit instruction, students aren’t learning critical thinking skills.

Part of the problem is that, other than specialists working in the area, few people are really clear about exactly what “critical thinking” is.

Universities, in general, don’t teach it either (they merely assume it is taught). So, aside from attempts in the popular literature to remedy the situation, business schools are often left floundering.

They are supposed to produce graduates steeped in ‘critical thinking and problem solving’ without a clue about how to go about doing it.

Given the parlous state of corporate reputations today, there are three questions worth asking:

Business & Economics

Why that Instagram post may cost you more than you think

1) Are current approaches to teaching critical thinking in business education effective?

2) Do business students really learn to apply critical thinking skills to a variety of business problems and in business-related situations?

3) Is critical thinking specifically inculcated in professional practice in business contexts, so that graduates seamlessly transfer these skills to the corporate world?

Our study of thirty years of business education literature, published recently in the journal, Studies in Higher Education, suggests these questions simply aren’t being clearly answered.

A definition of 'critical thinking' is sorely needed for starters, and currently there isn’t one dedicated to commerce-related disciplines.

This is ironic given that critical thinking is considered so necessary for success in the 21st century.

In fact, one recent report ranks critical thinking skills as higher than skills in “innovation” and “application of information technology”.

Having these skills also results in a higher mean annual salary. Moreover, demand for it among employers has risen 158 per cent and is described as the “most desirable” skill in new business graduates.

This being the case, why aren’t we defining it properly and teaching it effectively?

Business & Economics

Improving the finance sector for all Australians

Canvassing the landscape

Our study is an attempt to better understand the landscape of critical thinking in business education.

We investigated all available research literature related to critical thinking in business education in a survey of publications in the field between 1990 and 2019.

Three things really stood out.

First, critical thinking in the business literature is often confused with skills like ‘problem solving’. In reality, ‘problem solving’ is quite different from ‘critical thinking’.

A key feature of critical thinking, according to one well-known definition, is being reasonable and reflective, but some problem solving only requires rote thinking.

Sometimes problem solving requires thinking skills, like how best to balance profit and loss statements, but not critical thinking skills – rational, reflective thinking.

Some business-related problems, for example, require emotional intelligence, which is thinking that is neither rational nor reflective.

In other words, while critical thinking often refers to ‘problem solving’, not all problem-solving is an example of critical thinking.

Critical thinking consists more of ‘habits of mind’ providing a framework in which problem solving can occur. Often, these distinctions aren’t clear in business education literature.

Business & Economics

The trouble with banking culture

Secondly, research into critical thinking in business education has no particular focus area in commerce-related disciplines.

In a way this shouldn’t be surprising.

The nature of critical thinking is something with which even experts in the field disagree, so it should be expected that business academics haven’t tackled the subject head-on.

Still, its omission in terms of relevance to particular areas of business education research is startling.

How is it possible to educate for critical thinking if teaching for critical thinking is not front and centre of business education? Where does it belong? We need to find out.

Thirdly, discussions about critical thinking in business literature has shifted in thirty years of research in the area.

The concept of critical thinking in business has gone from a generalised and amorphous benefit, to having a more pragmatic focus in terms of addressing real-world issues and concerns.

It is now seen in terms of improving issues like managerial practices or managing tensions between business and the public interest.

This probably stems from businesses now having to engage in fair practices and competition and a consequential greater sense of responsibility and accountability to customers, stakeholders and the society.

Critical thinking is considered as a way for students to learn to navigate ethical issues in increasingly complex business environments.

So what could this all mean for the future of its application in business?

Business & Economics

Weighing up the policy responses to banking misconduct

What have we learnt?

What lessons can be learned from the business literature in terms of educating for critical thinking? In particular, how should we educate the next generation of business leaders to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past?

A definition of critical thinking dedicated to business disciplines is, naturally, preparatory to an understanding of how to best teach it.

What do business schools mean when they say they “produce critical thinkers and problem solvers”? Do they know what they mean? Without a clear definition of critical thinking, it is unclear how one is supposed to know if one has successfully acquired it.

To avoid corporate disasters of the future, educating business leaders must involve teaching them to be disposed to be critical.

There is a great deal of work done on critical thinking dispositions in the psychological and philosophical literature, little of which has filtered into the domain of business education.

Disturbingly, discussions on how to cultivate critical thinking dispositions is missing in the business education literature.

This is surely essential for educating business leaders.

Being disposed to be critical means, at minimum, being open-minded and fair-minded with regard to divergent views, seeking and offering reasons, being diligent in seeking relevant information, having a discrepancy-seeking attitude, exhibiting mindfulness, inquisitiveness, maturity, a preparedness to participate in community as well as displaying honesty, being caring, empathetic and concerned for others.

These dispositions are prima facie among the important ones that business students should develop in their journey to being business leaders.

But then, Bernie Madoff had all these in spades, didn’t he?