Health & Medicine

Simple ways to support people dealing with traumatic events

Too many firefighters have already died during Australia’s catastrophic bushfires this summer; a new project is looking back, honouring the stories of historical firefighters who lost their lives

Published 13 February 2020

This Australian summer brought with it devastating bushfires affecting many communities around the country.

In Victoria, the bushfire season is frequently at its peak in February, but this summer has seen severe fires burning out of control much, much earlier.

The hot northerly winds scorched parks and gardens, bringing soaring temperatures which all added to already hazardous conditions, fuelling the bushfires and forcing thousands to flee.

Rural communities in Victoria, with a savage history of catastrophic bushfires, have witnessed volunteers from around the world putting their own lives at risk to save animals, property and human lives.

And the cost of bushfires in terms of human lives can be enormous.

Health & Medicine

Simple ways to support people dealing with traumatic events

The loss of any life in a bushfire is traumatic but, as has occurred this summer, the death of firefighters always shocks us to the core.

The sacrifice of a life when coming to the aid of others is regarded as one of the most selfless acts of bravery and heroism.

With the fire season still active, Victorians have already honoured some of the firefighters killed as they worked to save bushland, houses and lives – David Moresi, Mat Kavanagh and Bill Slade.

Sadly, they are unlikely to be the last to perish – but new research has brought to light some of the stories of Victoria’s historical firefighters who lost their lives.

Last year, I began work on a commission from the Victorian Department of Environment, Land, Water, and Planning (DELWP) to investigate the historical deaths of people who worked for the DELWP and its precursor organisations including contractors and organisations that operated under licences from the Victorian Forestry Commission.

My research, with Professor Andrew May from the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies, found how whole families in the early twentieth century, children included, perished with the men whose job it was to fight bushfires.

Much like today, a coronial inquest was usually held after a major Victorian bushfire, as well as inquests for individuals who died in workplace accidents. So, my research started with investigating these, often graphic, historical records.

Danger lurks in all forests but falling trees, runaway timber carts, bulldozer accidents and a helicopter accident were all the subject of coronial inquests.

Some accidents were witnessed by other people, others happened on lonely bush tracks with the victims not found until days later.

But bushfires always play a part.

The deadly bushfire days, Black Sunday on 14 February 1926 and Black Friday on 13 January 1939, saw many forestry workers lose their lives, and as we now know, their families with them.

In 1926, Thomas Donald worked as a mill hand at Grant’s Mill, near Warburton.

On 14 February that year, devastating fires roared through the Victorian forests, sweeping across Gippsland, the Yarra Valley, the Dandenong Ranges and the Kinglake area.

The fires had started in late January, but wind gusts of up to 97 kilometres per hour led to the fire fronts joining up on 14 February.

Grant’s Mill was burned to the ground and Thomas Donald died near the blazing building. Tragically, his wife Mabel Donald, perished along with their three little ones, William aged six, Leslie aged four and Jack aged three.

On the same day, over the mountain range at Gilderoy, Worrley’s Mill was similarly consumed.

Forty-five minutes after sitting down for a midday meal, the fire forced everyone to flee. Mill worker Edgar Walker’s body was found along a timber tramline; huddled nearby was the body of his wife Ivy trying to protect her children Albert aged four and Kenneth, just three.

Unlike many bushfire deaths, it is the fact that whole families died at a place of work that sets these tragedies apart.

Timber working contractors were not drive-in, drive-out workers – roads and vehicles were much too rudimentary. Workers frequently lived at the mills and raised their families under the towering trunks of the forest giants of the mountain ash.

In 1939, after several years of drought, Victoria was hit by high temperatures and strong winds. Several fires had been burning since late December, but in January, the extreme conditions turned the blazes into a massive fire front.

Towns were burnt to the ground, and 75 percent of the state was covered in smoke.

Sciences & Technology

Why Australia’s severe bushfires may be bad news for tree regeneration

Five years after Black Friday, in January 1944, bushfires again devastated Victoria with 19 lives lost and over 500 homes destroyed.

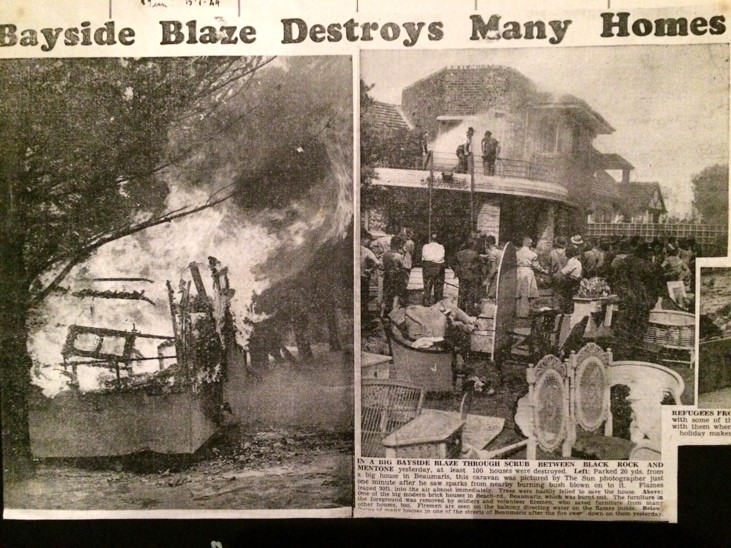

But in a sobering reminder that bushfires can strike anywhere, a devastating bushfire raged through the Melbourne seaside suburbs of Cheltenham and Beaumaris.

In scenes reminiscent of seaside Mallacoota in January 2020, hundreds of people evacuated to Beaumaris Beach and Ricketts Point.

Images of war, so frequent on the front page of the papers at that time, gave way to images of horror and destruction with the house losses varying from 58 to 100 homes in the wider area.

As a result of my research, 19 names of workers of contractors and the state workers who died fighting bushfires in the Victorian Forestry Commission forests are now being put forward for inclusion on the Honour Roll at the National Emergency Services Memorial which sits overlooking Lake Burley Griffin in Canberra.

A further 65 names of people who died were highlighted by the research, irrespective of the nature of the workplace accident, for consideration to be memorialised at one of the DELWP offices in Victoria.

Sciences & Technology

Don’t blame nature for the disasters we’ve created

Sadly, the list of names continues to increase.

Bushfires are tragically fought by families, neighbours, volunteers, and professional firefighters, all risking their lives. Facing a wall of roaring flames is a terrifying prospect, too often with the direst consequences.

The deaths of these individuals must be honoured as continual reminders of the fragility of the human condition against nature, but also of the heroism that is often remembered posthumously.

Banner: Geoff Bull’s Walkley Award winning picture of firefighters in front of an advancing fire at Panton Hill in 1962. Herald Sun