Plant diseases no match for man’s best friend

Sonja Needs combines her training in winemaking and viticulture research with her passion for canine search and rescue to track down pests and diseases

Published 9 December 2015

My undergraduate degree was in science, with majors in physiology, microbiology, medical laboratory science and environmental science. I later completed a postgraduate teaching degree and studies in forensic toxicology.

After my undergraduate degree I worked at CSIRO in Merbein, near Mildura. Itwas as a winemaker in the experimental microvinification winery, looking at alternative wine grape varieties. So, I’ve got a background in winemaking and viticulture, but my hobby is dog training.

I always loved animals. When I was young I had collies that I bred, showed and trained in obedience, agility and tracking. It was the tracking that I found interesting and it was the pathway to my next major pursuit, search and rescue. It was something I could not do in Mildura while working at the CSIRO, but then I took a position with the University of Melbourne. Not long after, I got Luther, an eight-week-old German Shepherd puppy.

Luther and I volunteered with Southern Cross Search Dogs in urban search and rescue. We looked for people trapped in building collapses, landslides etc. I started training with him and we became operational. There were only a handful of operational search dogs in the country at that stage.

We regularly went to South Australia for training exercises. It was with the fire brigade, where they’d simulate a disaster with a building collapse. They’d have the sirens, the explosions, the fires … they would bury actors in the rubble and we would go and find them.

When he was six, Luther developed degenerative canine myelopathy. It’s a condition similar to motor neurone disease. It’s a horrible disease which affects a large percentage of German Shepherds, though most of them don’t develop it until they’re much older. Luther was still mentally fine, but physically not able to do search and rescue.

Looking for another job for him is what got me into my current research in using dogs for detection.

I’m particularly interested in pests and diseases in vineyards and wineries. Using dogs is an emerging field, mainly in conservation. We’re now using dogs as detectors for beehive collapse, termites and fire ants, and finding endangered species.

The major advantage dogs have as a detection tool is that they’re versatile. One of the reasons you would use dogs in research is to see whether certain diseases have scent. That’s some of the research I have done, examining the possibility that Eutypa, a fungal disease which lives in the trunk of the grapevine has a detectable odour.

In the field, dogs are fast. Imagine a person trying to walk through a dense scrubland or a thick crop looking for a weed or insect pest … we’re very limited in that environment, while a dog could cover an area like that extremely quickly. Dogs also have a greater sensitivity to volatile molecules than most mobile gas chromatography detectors and they can sort and discriminate scents where machines have difficulty. At the moment we really don’t have any instrumentation that is quite as good as a dog’s nose.

Once a dog is trained in detection they are able to be trained in multiple odours. Each odour added takes less time to get the dog reliable in their indication. Explosives and drug detection dogs can learn 12 or more scents easily – we don’t know what the limitation of how many odours we can train them on is. Most dogs will search for a 20-minute period in every hour.

As well as being able to detect volatile molecules that are as dilute as one part per trillion, dogs have a vomeronasal organ in the roof of their mouth. It’s an organ specifically designed for detecting hormones and pheromones – which makes them ideal for use in detecting insects.

Along with Eutypa, I trained Luther in Brettanomyces detection, a type of yeast that becomes a fault if it affects the wine. It loves to live in the wood of oak wine barrels but can also live on machinery and other surfaces in wineries. There are a couple of different chemical markers for brettanomyces and Luther was trained on both of those and would indicate them very reliably. Unfortunately the degenerative myelopathy took him before I could go further with this research.

When I lost Luther I got Keely, a border terrier. She helps out with teaching in the Animal Science Breadth subjects and she’s well versed in demonstrations.

She is also trained in detection. We start the dogs off on a neutral substance – a specific volatile substance that they will not encounter elsewhere in their environment. Once they’re reliable on the first odour, we can shift them onto whatever substance that we want, so we will swap her off to pests and diseases when we’re ready.

Bertie the black Labrador is also trained on neutral substances. He belongs to wine lecturer Chris Barnes. Bertie is the unofficial wine breadth subjects mascot, he attends all the lectures, and comes to the Dookie winery when the students are there, but he’s also a very good detection dog.

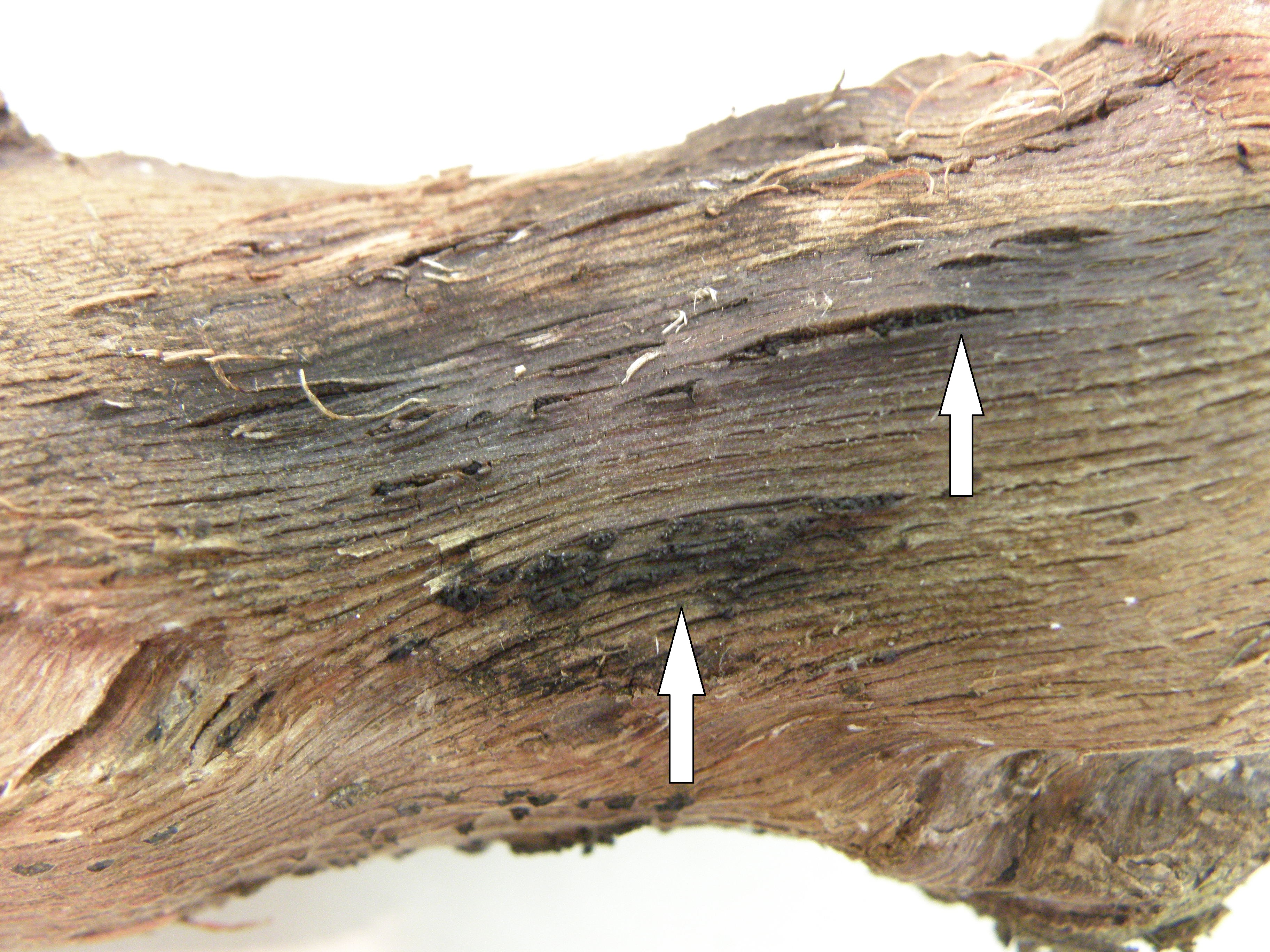

Soon I hope to do some work on phylloxera. This is an insect that feeds on the roots of vineyards. I am not just interested to see if dogs can find it, I want to know the best part of the lifecycle for dogs to detect the phylloxera. They’re most active in February – but it’s also when wineries harvest, the busiest time of the year for them. So I want to see if the dogs can sniff out the phylloxera in the winter when the vines are in their dormant period.

I also want to know how soil type, moisture levels and depth affect the dog’s ability and reliability. If you were coming to search a vineyard, you want to know how the conditions affect detection in the vineyard so that when you use dogs, you’re using them at the most ideal times. So understanding these conditions will allow dog teams to be best deployed.

As told to Stuart Winthrope.

Banner image: Roots damaged by phylloxera. Picture: Joachim Schmid/Wikimedia Commons.