Arts & Culture

How literature helps us interpret the human face

In an age of pervasive surveillance and social media promotion, reading poetry matters more than ever as we try to come to terms with our technologically-led society

Published 9 July 2021

During the twentieth century, the FBI closely monitored poets, read their work, and speculated about their political and artistic intentions. American surveillance agencies even hired people with backgrounds in poetry to be spies and code breakers because of their skills in close reading, language analysis and critical thinking.

From Yale’s 1943 graduating class alone, at least forty-two young Bachelor of Arts students entered intelligence work for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the wartime forerunner of the CIA.

As historian Robin W. Winks observes in his 1987 book Cloak & Gown: Scholars in the Secret War, 1939-1961, many of these were English graduates who could apply literary techniques to intelligence analysis and cryptic expressions.

While it’s hard to think of poets as spies, poetry and surveillance actually use very similar styles of information gathering such as close observation, abstraction, subversion, fragmentation and symbolism.

Arts & Culture

How literature helps us interpret the human face

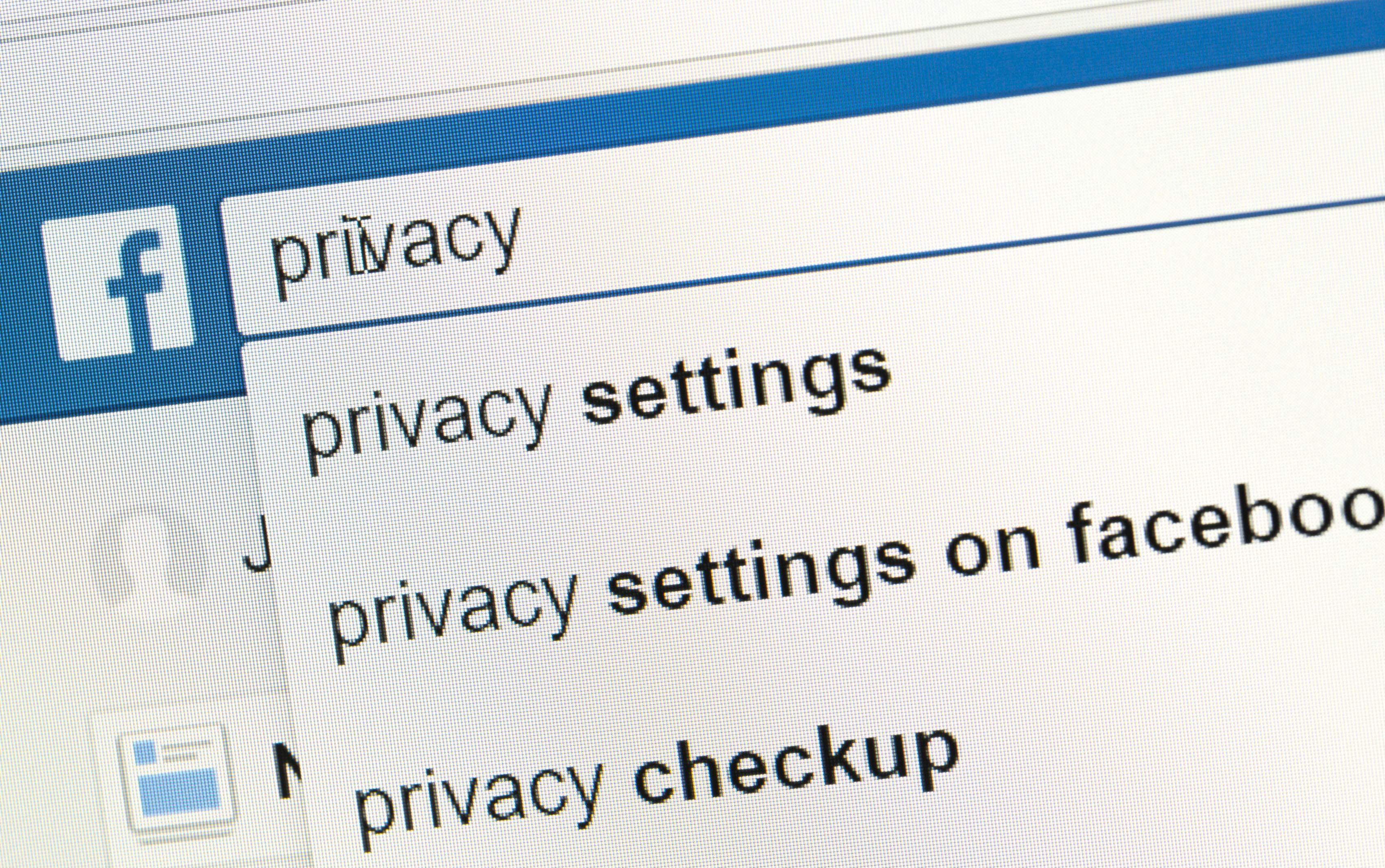

Today, we live in an era of unprecedented surveillance. Our personal information is routinely tracked and collected, while sophisticated analytics and algorithmic systems are being designed to predict, influence and ultimately control our choices and behaviour.

And it’s changing the nature of how we see ourselves. The ubiquity of surveillance and social media is challenging the very idea of the private individual as people increasingly adopt public personas. The scholar Julie Cohen described digital culture as bringing about a ‘surveillance-innovation complex’ in which surveillance is now privatised, commercialised and increasingly participatory.

To help us comprehend, and perhaps ultimately better shape, the complex social and technological change we are caught up in, we could do a lot worse than turn to that close cousin of surveillance – poetry.

In fact, new and growing audiences are already reaching for poetry in the context of increasing privacy violations, a rising online confessional culture and a problematic loss of boundaries within the virtual and online worlds being created for us.

When it comes to literature that helps us understand the machinations of surveillance, many people immediately think of George Orwell’s dystopian science fiction novel Nineteen Eighty-Four or Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, in which citizens are manipulated into an intelligence-based social hierarchy.

After all, in the aftermath of the Cambridge Analytica scandal and the ‘alternative facts’ rhetoric of the Trump presidency, sales of dystopian fiction skyrocketed. Orwell’s 1949 classic even hit No.1 on the Amazon bestsellers list.

Arts & Culture

Artists, environment and truth telling in Indonesia

But as The Guardian has recently reported, sales of poetry have soared with ‘political millennials’ reported to be reading poetry to search ‘for clarity’ in a turbulent world.

As Dina Gusejnova, an Assistant Professor in International History, observed in a 2019 interview with the London School of Economics, readers have always ‘been drawn to poetry in the context of political crises which fragment and challenge society.’

Poetry helps us think about fundamental issues of surveillance because poets themselves have always been professional observers. From Shakespeare to Robert Frost to Nikki Giovanni, the history of poetry is bound up with key surveillance concepts such as seeing, hearing, listening, watching, analysing and deciphering.

The art of poetry itself is also about the careful evaluation of complex human matters such as privacy, identity and truth. Each of these are core to surveillance and the effects that surveillance technology has on our lives.

Take, for example, American poet Emily Dickinson’s well-known poem “I’m Nobody! Who are you?,” first published in 1891:

‘I’m nobody! Who are you? Are you nobody, too? Then there’s a pair of us – don’t tell! They’d banish us, you know.

How dreary to be somebody! How public, like a frog To tell your name the livelong day To an admiring bog!’

Arts & Culture

Dying apart, buried together

This short, deceptively simple lyric is one of Dickinson’s most popular poems, not just because of the universality of its theme of identity but also because, with each new twist in our frenzied media-driven world, the poem’s commentary on privacy and the inner life takes on renewed meaning.

The poem’s key suggestion that anonymity is preferable to fame is especially pertinent to the neoliberal or free market conditions under which individuals are now prepared to give up ever more personal data in order to build a personal brand.

Poetry also helps us think about questions of authenticity, interpretation, and perception, all of which are crucial to understanding the complex configurations of surveillance.

Wallace Steven’s “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” (1917), for example, presents a range of different perspectives of a single blackbird, each fragment evoking certain feelings in the reader about a seemingly unassuming animal.

Likewise, John Keats’ oft-quoted sonnet “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” (Chapman being the translator), examines the ways that great poetry can move us to consider different and unexpected ways of seeing the world. Keats writes: ‘Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold / Then I felt like some watcher of the skies.’

The multi-layered, coded and highly subjective intricacies of poetry allow us to think about knowledge, information, and even data, in a new light. It gives us tools of discernment and nuance to more creatively tackle the unprecedented volumes of visualisations, statistics and digital data that confront us every day.

Arts & Culture

What was it like to be a child in the Roman Empire?

Like the arts as a whole, poetry positions us to question and contextualise technology, as well as to grasp irony, abstraction, paradox and change.

In the opening stanza to his 1934 poem ‘Choruses from The Rock,’ American-English poet T.S. Eliot questioned:

‘Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?’

These lines powerfully illuminate many issues confronting society today, just as they did in Eliot’s time – a period characterised by a rapid shift from traditional industries to an economy organised primarily around information technology.

As Eliot’s lines suggest, poetry helps us to see the world in imaginative and non-reductive ways: to find, as it were, the knowledge in information.

Dr Sumner’s forthcoming book ‘Lyric Eye: The Poetics of Twentieth-Century Surveillance’ is published by Routledge and will be available from August.

A version of this story also appears on The Mandarin.

Banner: Getty Images