Pre-colonial Australia: natural wilderness or gentleman’s park?

Professor Marcia Langton tells why the book that rewrites the history of Aboriginal land management before white colonisation makes it to her list of the 10 greatest books ever written

Published 25 September 2015

Unlike New Zealanders, whose education is rich in Maori language, history and customs, most Australians have only a sketchy understanding of the traditions of their country’s first peoples.

Misconceptions about the environment and first contact at the time of British colonisation, in place of informed knowledge, abound.

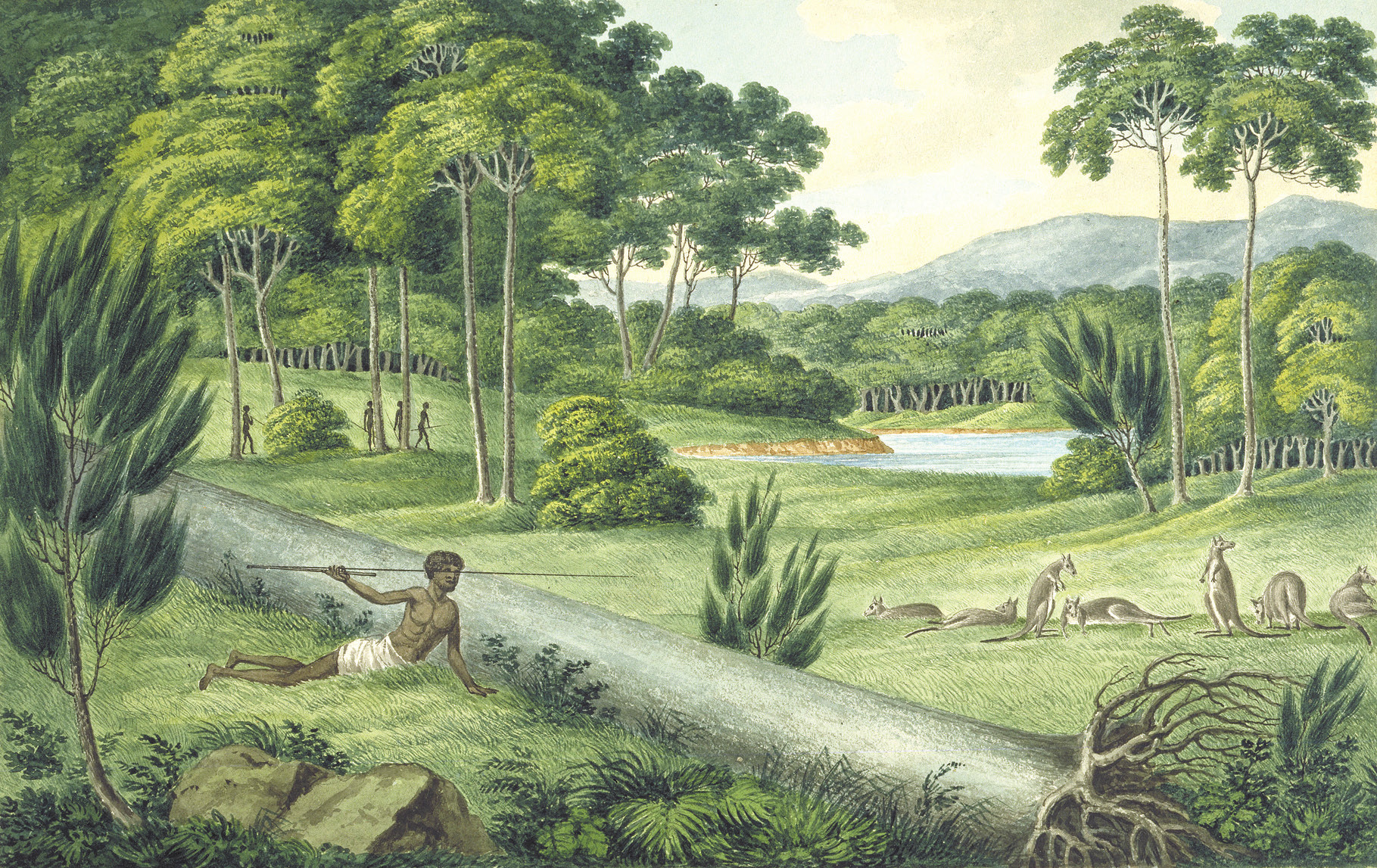

One such assumption is that our land of “droughts and flooding rains” has always been a natural and untamed wilderness. Another is that the early colonial painters distorted their views of Australia with romantic and nostalgic overlays that harked back to the European landscapes of their birth. A further, and more problematic misconception, is that the country’s traditional owners were primitive hunters and gatherers who wandered the land relying on chance for survival.

Reaction and non-reaction

On publication in 2011, Bill Gammage’s The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia won universal praise in political and literary circles, including the Prime Minister’s Prize for Australian History and the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award.

But it hardly caused a ripple – from then till now – in dislodging common assumptions long held by many Australians, first learned in the classroom and often trotted out since.

Revealing pre-colonial Australia as a landscape of grassy patches, open woodlands and abundant wildlife, Gammage’s groundbreaking book details how Aboriginal people followed an extraordinarily complex system of land management. This system used fire and the life cycles of native plants to ensure plentiful wildlife and plant foods throughout the year, all based, says Marcia Langton, on an encyclopaedic knowledge of their environments, seasonal weather patterns and biota.

One of the 10 great reads

For Professor Langton, Chair of Indigenous Studies at the University of Melbourne, and widely published anthropologist and geographer, The Biggest Estate is so significant and important a contribution to Australian historical, anthropological and environmental studies, that she nominates it as her choice in this year’s series of 10 Great Books hosted by the Faculty of Arts.

“As with every book one reads, the experience is highly subjective and personal,” she says.

For me, an audience of one, Bill Gammage’s book was a eulogy for a lost place albeit a eulogy studded with historical and scientific detail.

“It’s a body of detail that channels his extraordinary interpretation of a cultural history of an entire continent and its islands with a determined narrative, logic and sentiment.”

In The Biggest Estate, Gammage supports his thesis with exhaustive and compelling research from primary sources to prove that prior to British colonisation in 1788, Australia was an “unnatural” landscape, carefully and systematically managed by its traditional owners to ensure that “life was comfortable, people had plenty to eat, few hours of work each day, and much time for religion and recreation.”

1788, a character in its own right

But to earn a place on a list of 10 of the greatest, a book must be much more than a well argued, albeit irrefutable, treatise not previously presented.

According to Professor Langton, Gammage qualifies for his spot on the top 10 great books list courtesy of an ingenious historiographical device and by building up and rolling out an intriguing mystery at every turn of The Biggest Estate.

The historiographical device, she explains, is using ‘1788’ as a character exemplifying the landscape of entire continent at the time – from the northern-most tip of the mainland, to the southern-most point of Tasmania, and coastal and inland places in between. A landscape that was referred to, reference after reference in writing, by white explorers, settlers and surveyors as being akin to “a gentleman’s park”, “a landlord’s estate,” and in the paintings of early colonial artists.

It is this aspect of Gammage’s great book that for Professor Langton defines its achievement and informs the title of his great book, one that he arrives at by comparing his examples of different climates and terrain and among different plant species.

“In 1788 a Tasmanian would have recognised a Queenslander’s care for country, if not how it was done,” Professor Langton quotes from Gammage. “This comparison alone, seemingly so long sustained, implies universal end served by myriad local means, and justifies accepting what Aborigines did as managing a continental estate.”

Some departures of opinion

Despite her overwhelming admiration for what she considers overall to be a tour de force, Professor Langton takes issue with some aspects of The Biggest Estate on Earth. Referring to some “quibbles” about Gammage’s use of the term “totem” in his discussion of the relationship of Aboriginal religion to land management practices and his less than complete understanding of Aboriginal laws, Professor Langton draws on her own thesis of Aboriginal Ontology of Being and Place to explain her departure from Gammage in these respects.

“What is missing from Gammage’s grand and fascinating work is an understanding of the laws that Aboriginal people followed and, here too, like the land management system, the universality of this body of laws,” says Professor Langton.

Her other main quibble relates to Gammage’s assumption that none of the 1788 traditions continues and the 1788 landscapes no longer exist.

“This is not the case,” Professor Langton says.

Using fire to manage the land, an ongoing practice

“For more than 30 years I have been visiting Arnhem Land, and what I wrote about their fire and land management traditions in 1998 in Burning Questions is still accurate.”

“The knowledge and practices which sustained the Australian biophysical landscapes during that period, at least since the Holocene, are still applied by Aboriginal groups throughout the area,” says Professor Langton.

She offers as an example the case study of a Yolngu man, Malngay Guyula who, with his fellow clan members, inherited their traditional estates in the southeastern part of the Arafura wetlands.

“Malngay and his kin burn their estates seasonally, according to tradition, and do so on foot across a large area,” says Professor Langton. “The landscape patterns created by his efforts are evident from the air, fired buffer zones at the edges of the plains protecting stands of monsoonal rainforest on hilltops and in gorges.”

In the fourth of her 2012 Boyer Lectures, Professor Langton used Geoffrey Blainey’s term “fire stick farming” (which he explained in 1975 in Triumph of the Nomads). This concept explains how the Australian continent has been shaped by wildfires for tens of thousands of years by Aboriginal people using fire across vast landscapes in a mosaic pattern of burning that reduced the vegetation after each monsoonal wet season.

She concedes that in another part of Arnhem Land these ancient practices had almost ceased as a result of assimilation policies which included bringing Aboriginal populations into small townships in the 1950s.

“But the traditional Aboriginal owners of the upper Cadell River re-established their community at Kapawanamyu,” she says, “and from this base, they worked with the Bawinanga rangers from the Maningrida township, scientists and researchers, to continue traditional control burning their estates for biodiversity conservation purposes.”

Looking to indigenous cultural practices for direction forward

“Small cool fires lit throughout the year by traditional owners protect these as well as other vegetation communities — woodlands, sandstone heath, and riparian rainforest — from the wildfires.

“If you’ve ever stood in the path of a wild fire burning inexorably towards you, as I have, you’ll appreciate the sheer terror it engenders,” says Professor Langton.

“With climate change creating havoc in bushfire prone areas around the world, we would all do well to learn from the cold-fire burning and scrub clearing practices Aboriginal people have perfected over millions of years, and have been so beautifully and painstakingly explained by Bill Gammage in his great book, The Biggest Estate on Earth.”

Professor Marcia Langton presented Bill Gammage’s The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia to this year’s Faculty of Arts 10 Great Books series. She will be the orator for the 2015 Narrm Oration to be held at the University of Melbourne on Thursday 19 November at the Copland Theatre (The Spot).

Banner image: Joseph Lycett’s Aborigines hunting kangaroos, circa 1820 (featured as image 53 in Bill Gammage’s Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia) shows how systematic burning by Aboriginal people was used to create edges, grass corridors and verdant green grasslands, and enabled trees to grow straight in tall thick forest with little undergrowth. Picture supplied.