Putting the real in fantasy superheroes

Stan Lee’s superheroes are grounded in an emotional reality and optimism that we can still save the world

Published 14 November 2018

Many of us will recognise Marvel’s great comic writer Stan Lee from his regular cameos in Marvel movies—a trend we’ll miss in the future following his passing this week. Lee became such a fixture in the Marvel brand that he appeared in films for characters he never created.

But one that stood out to me was Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2. Of the Guardians, Lee can only be credited for Groot, but he features briefly with characters he did create: The Watchers, obscure bald super-beings from Marvel’s cosmic lore. The godlike Watchers preside over cataclysmic events in the Marvel universe.

There was something ironic and profound about a larger-than-life deity, who was not so much a creator spirit but a reliable presence, with an uncanny sense for those moments when the world was about to change forever.

Comic purists argue that Lee served Marvel more as a figurehead than a writer. Lee’s relentless publicity was, as much as his writing, what elevated superheroes to the mythic figures we know and love. We might agree he had an affinity for outlandish individualists who sprang to life beyond the pages of comic books.

Lee was unarguably an intelligent businessman, but what stood at the core of his titanic mythos was his ability to tell stories that mattered. His superheroes spoke to the time, and readers understood.

In the 1960s, Marvel mirrored the civil rights movement through the marginalised X-Men, and subtly criticised the Cold War with Iron Man. In a 1970 editorial going viral again this week, Lee fought back against the sentiment ‘that comics are supposed to be escapist reading, and nothing more.’

Lee argued that ‘a story without a message, however subliminal, is like a man without a soul.’ After all, Lee claims: ‘None of us live in a vacuum – none of us is untouched by the everyday events about us—events which shape our stories just as they shape our lives.’

Superheroes have always occupied an ambivalent space, politically. Some see their bold colours and their optimistic narratives as escapist pulp. It’s not a stance to be dismissed out of hand. Henry Jenkins once defended his love of comics by claiming: ‘I was feeling some great responsibilities in my life and I figured I could use some great powers about now.’

Others read overarching conservative narratives in superheroes: they defend the status quo, championing exceptionalism, hyper-masculine violence, and a primary-coloured morality. There’s a risk of tautological belief at the core of the genre: superheroes do the right thing, and the right thing is what superheroes do. Yes, they are ridiculous. It should feel implausible that a titanic figure can carry the weight of our hope and our trust – that someone can make the bad things go away.

Arts & Culture

Nanette, self-deprecation and when not to use it

But at the core of that tension, between cynicism and escapism, is something we can’t dismiss so easily: how absurd it is to hope. Of all the fantasies to entertain, superheroes ask us to believe that we can make the world a better place. In Lee’s famous words: ‘With great power, there must come great responsibility.’ When we have the power to do good, we have the responsibility as well.

The other way Lee’s stories mattered was in their personal resonance. Lee’s writing, from his first short story in the back of Captain America Comics in 1940 to the game-changing Fantastic Four, emphasised emotional reality at the core of amazing fantasy. Lee’s superheroes are as troubled by lost love as they are by villains. The Avengers joke, bicker, flirt, and weep. The line of great power and great responsibility is delivered in darkness, as Spider-Man mourns the loss of his uncle.

In Lee’s stories, the drive to do the right thing comes from the heart, not the head (or the bicep). His stories are melodramas, built on the conceit that what we care about and who we care about are inextricable.

In this day and age of rising political cynicism, to actually care can seem a silly and painful thing. How fantastical seems the possibility of making the world a better place. How little responsibility matters to those with great power.

But these heroes endure. G. Willow Wilson’s superhero Ms Marvel reminds herself of the Quran’s teachings: that she cannot save everyone, but to save one person is to save all. Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Captain America grapples with the staggering distance between the American dream and the American reality. Felipe Smith’s Ghost Rider gives voice to those who shoulder a lifetime of responsibility, with no great power in sight. These stories carry Lee’s legacy well.

They give us the relentlessly optimistic belief that in spite of it all, we might save the world, and we might save each other.

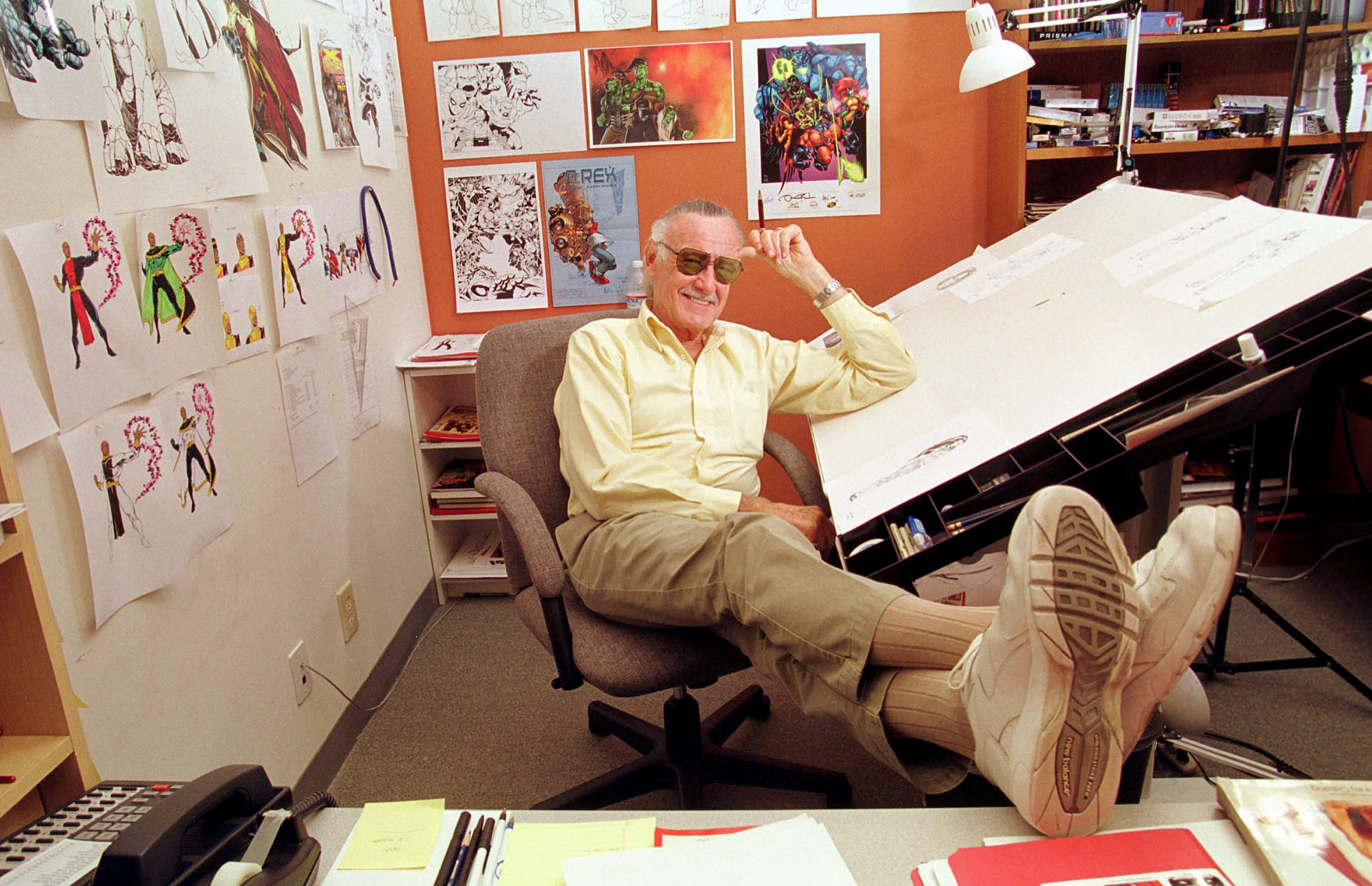

Banner Image: Marvel comic book character creator and writer Stan Lee in his Los Angeles office. Picture: Kim Kulish/Corbis/Getty Images