Education

Changing the shape of teaching

As the literary landscape evolves, so does how the subject is taught in schools. How are our new teachers coping with the challenge?

Published 13 October 2016

As a young English teacher in an outer suburban secondary school in Melbourne in 2003, Larissa McLean Davies and her colleagues in the English department would often have spirited discussions about choosing texts for the school’s curriculum.

“One of the hottest issues in any school English department is what texts to select for the following year’s English classes,” she says.

“At VCE (Year 12) level you have to choose texts from a list provided by the Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority. At other year levels teachers use their own discretion to select and agree on the texts within the curriculum guidelines.

“But people have very strong views about the kinds of literary experiences students should have. Some teachers have strong views that Shakespeare should be included at Year 10 or earlier, and others think that’s not appropriate. Others are concerned about getting enough Australian literature into the curriculum, or choosing texts from different cultures.”

Fast forward 16 years and Larissa McLean Davies is now an Associate Professor at the University of Melbourne’s Melbourne Graduate School of Education.

The global boom in genres, from crime fiction to memoirs, from fantasy fiction to young adult fiction, presents even greater choices for English teachers faced with the task of selecting school texts. And even now some of the fundamentals remain hotly contested, such as how to teach literature and what purpose literature serves.

Associate Professor McLean Davies is leading a new research project investigating how English teachers are faring in this rapidly evolving and expanding literary landscape.

The project, Investigating literary knowledge in the making of English teachers, will track the experiences of teachers in their first five years of teaching in Western Australia, Victoria and New South Wales.

It will investigate the key factors shaping a new teacher’s literary knowledge as they move from their undergraduate English studies through teacher training and into their early careers as English teachers.

Education

Changing the shape of teaching

This includes how they are adapting to the demands of the Australian Curriculum, introduced in 2008, which requires English teachers to teach “Literature” as a main element of their English classes for students in Years 7-12.

Another trend in the making of English teachers – the rapid growth in the diversity of university literature courses that undergraduate students can study before they go on to train as teachers – will also be examined. Students can choose to specialise in courses ranging from feminist literature studies, to creative writing, to world literature, to multi-modal courses such as literature and film and many others.

“What constitutes literature in these undergraduate degrees is very different around the country,” says Associate Professor McLean Davies. “What might be considered as literary studies at one university might be very different at another university.

“In one university it may be that students undertake a survey of literature through the ages, in another university students might be looking at literature that has been forgotten, in another place it might be much more multi-modal and not necessarily only about the printed text.

“There are different ways of understanding the study of literature and we think that is likely to affect the way teachers coming in to pre-service teacher education programs understand what’s going to be the business of teaching English in schools.”

Preliminary findings from another study of mid-career schoolteachers by Associate Professor McLean Davies revealed some teachers tended to feel uncertain or less confident about their ability to teach literature compared with their confidence in teaching other elements of the English curriculum.

The new research project will be conducted over four years. It is funded by the Australian Research Council and includes a team of researchers from Victorian and interstate universities. The team includes Professor Lynette Yates of the University of Melbourne, Professor Brenton Doecke of Deakin University, Professor Philip Mead of the University of Western Australia and Professor Wayne Sawyer of the University of Western Sydney.

It will also survey representatives of state and territory-based curriculum authorities, teacher training organisations, university literary studies departments and professional associations representing English teachers.

Professor Philip Mead, Chair of Australian Literature at the University of Western Australia, says the huge array of literature studies at university is a reason students are attracted to the discipline of English, because it enables them to specialise.

But when these literature graduates begin their careers as English teachers in secondary schools, they encounter professional challenges in learning how to teach a set syllabus of texts.

Professor Mead says the research project will examine ways to help new teachers think about literary education in a broader, more coherent way, rather than through the prism of their specialist undergraduate course.

“Our hope is that we will be able to provide a conversation about how literature can be taught in the school classroom and talked about with students in a broad, sociable kind of way,” Professor Mead says.

“Out in society people enjoy literary texts in all sorts of ways, they talk about literature and they identify with it. That can also happen in an English classroom.

“We hope our research project will show how teachers can go into an English classroom and talk to students about any kind of literary text; that they have a framework to think about these things that goes beyond advising students that the class’s exercise today is reading Miles Franklin’s My Brilliant Career for gender issues or class issues alone.”

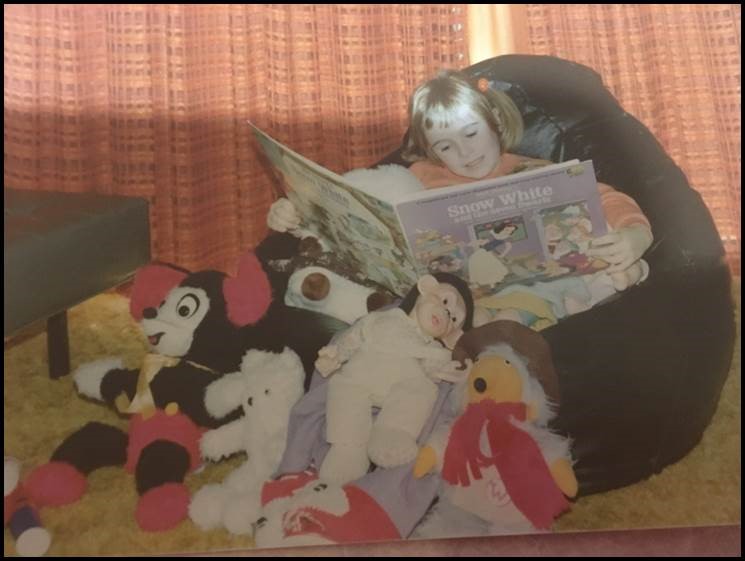

For Associate Professor McLean Davies, the study continues a lifelong love affair with literature, sparked by her grandfather, Charles Marshall, a Presbyterian minister who taught her to read when she was four. “My grandfather was an avid reader and the manse was full of books. Books were my best friends.”

She says the study’s findings will be used to improve the writing of English curriculums in schools and in undergraduate university courses by providing a clearer idea of the core purposes of the teaching of literature.

“We hope this study will help to form a bridge over the historical divide between those who teach English at universities and those who teach English in schools,” she says. “We hope it will create a shared discourse between universities and schools about what we understand the teaching of literature to be.

“Research like this into the teaching of literature hasn’t been done before. The project isn’t presenting a deficit model of the curriculum. Instead it’s saying that research evidence is helpful in the shaping of curriculum policy documents and the education of English teachers.”

Emily Frawley is an early career English teacher, working at a secondary school in Melbourne’s western suburbs. She completed an undergraduate arts degree, with a major in creative writing, before graduating with a Master of Teaching from the Melbourne Graduate School of Education.

Ms Frawley hopes the study’s findings and recommendations will help teachers make literature more appealing to students in English classes. She says teachers would welcome new strategies that encouraged students to see the reading and analysis of literature as an enjoyable, creative intellectual exercise rather than as a prescribed chore.

“The study might be able to help teachers, especially those teaching senior school students, to feel better equipped to help students to engage with a text on their own terms, and come to their own interpretation of it,” Ms Frawley says.

“That’s a more enjoyable and meaningful approach to the teaching of literature than relying on the faster option, which is ‘Here’s what you need to say and here’s the answer’. That sort of learning is not what English is about.”

Banner Image: Pixabay