Arts & Culture

Lucky discoveries of lost ancient history

In biology, phylogenetics reconstructs evolutionary relationships. The same technique is revealing the history of the New Testament

Published 1 August 2025

Our knowledge of ancient literature comes to us through the hands of scribes. The works of Aristotle, Galen and Ptolemy survived only because generations of copyists reproduced them by hand.

But copying was not a straightforward process.

Scribes sometimes edited as they copied – smoothing out contradictions, inserting interpretations, merging readings from different sources and, sometimes, just making mistakes.

Over time, these small changes accumulate.

In order to trace how a text evolved, modern-day researchers use a kind of reconstructed manuscript family tree, known as a stemma.

This tree not only helps us approximate the earliest recoverable version of a text; it also reveals how that text was read, reshaped and reimagined across centuries and cultures.

The larger the tradition, the harder the puzzle – and the New Testament Bible is one of the most complex traditions to survive.

Arts & Culture

Lucky discoveries of lost ancient history

Thousands of manuscripts still exist in the original language of Greek, alongside thousands more in translation – Latin, Syriac, Arabic and others – each with their own patterns of variation.

One recent estimate suggests the New Testament manuscript tradition contains half a million textual variants which works out on average of three or four for every single word.

Facing the weight of this information and its complexity, traditional methods can only take us back so far. Instead, scholars have begun turning to tools developed in an entirely different field.

One of the most powerful is phylogenetics – a technique pioneered by biologists to reconstruct evolutionary relationships by analysing how traits are inherited and change over time.

Now, it’s being used to untangle the history of texts.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists traced the virus’s spread by analysing tiny mutations in its RNA. The same principle can apply to manuscripts.

Just as geneticists can reconstruct transmission histories from genetic changes, textual scholars can trace the evolution of a text by comparing its variants.

As biologist Richard Dawkins once observed: “So similar are the techniques and difficulties in DNA evolution and literary text evolution that each can be used to illustrate the other.”

In the 1980s, Peter Robinson completed a PhD on Old Norse manuscripts.

Arts & Culture

The archaeology of olive oil in the ancient world

In 1991, he posted a challenge on a network bulletin board: could someone recreate his analysis using a computer?

More specifically, he wanted someone to re-create the table of relationships for around 44 different manuscripts of the Old Norse narrative ‘Svipdagsmál’ by statistical or numerical means alone – something he’d already done using external evidence and the traditional stemmatic method.

Biologist Robert O’Hara responded with a phylogenetic approach – and in five minutes, he’d replicated what had taken Robinson months by hand.

Since then, textual scholars have used phylogenetics to study manuscript traditions from The Canterbury Tales to the New Testament.

In my recent book, Codex Sinaiticus Arabicus and Its Family, I’ve explored how latest phylogenetic techniques from biology can help us trace the history of New Testament Gospel manuscripts.

Biologists recognise that not all genetic mutations occur at the same rate. I used this insight to look at manuscript traditions, allowing the model to distinguish between different types of textual change.

This is important because minor changes that did not affect the meaning tend to appear often, while large, substantial changes are less frequent.

By modelling these rates separately, we can now estimate how often scribes introduced particular kinds of changes – and in doing so, reconstruct the evolution of the text with far greater accuracy.

These changes might be small changes in spelling or the substitution of words with synonyms, all the way up to the addition or omission of whole sentences or paragraphs.

Arts & Culture

How do you crack the code to a lost ancient script?

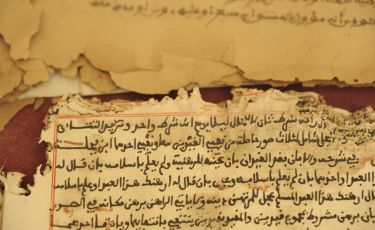

In 1975, a long-forgotten storeroom was discovered at St Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai Peninsula – one of the world’s oldest Christian monasteries, deep in the Egyptian wilderness.

Inside were hundreds of previously unknown manuscripts in Greek, Arabic, Syriac and other languages.

Among them was a remarkable discovery: a forgotten Arabic translation of the Gospels, from a Greek source.

I’ve traced the history of this translation and pieced together its story from the surviving manuscripts.

What makes this translation so striking is its preservation of hundreds of rare textual readings – subtle differences that shed light on how the Gospels were copied and transmitted.

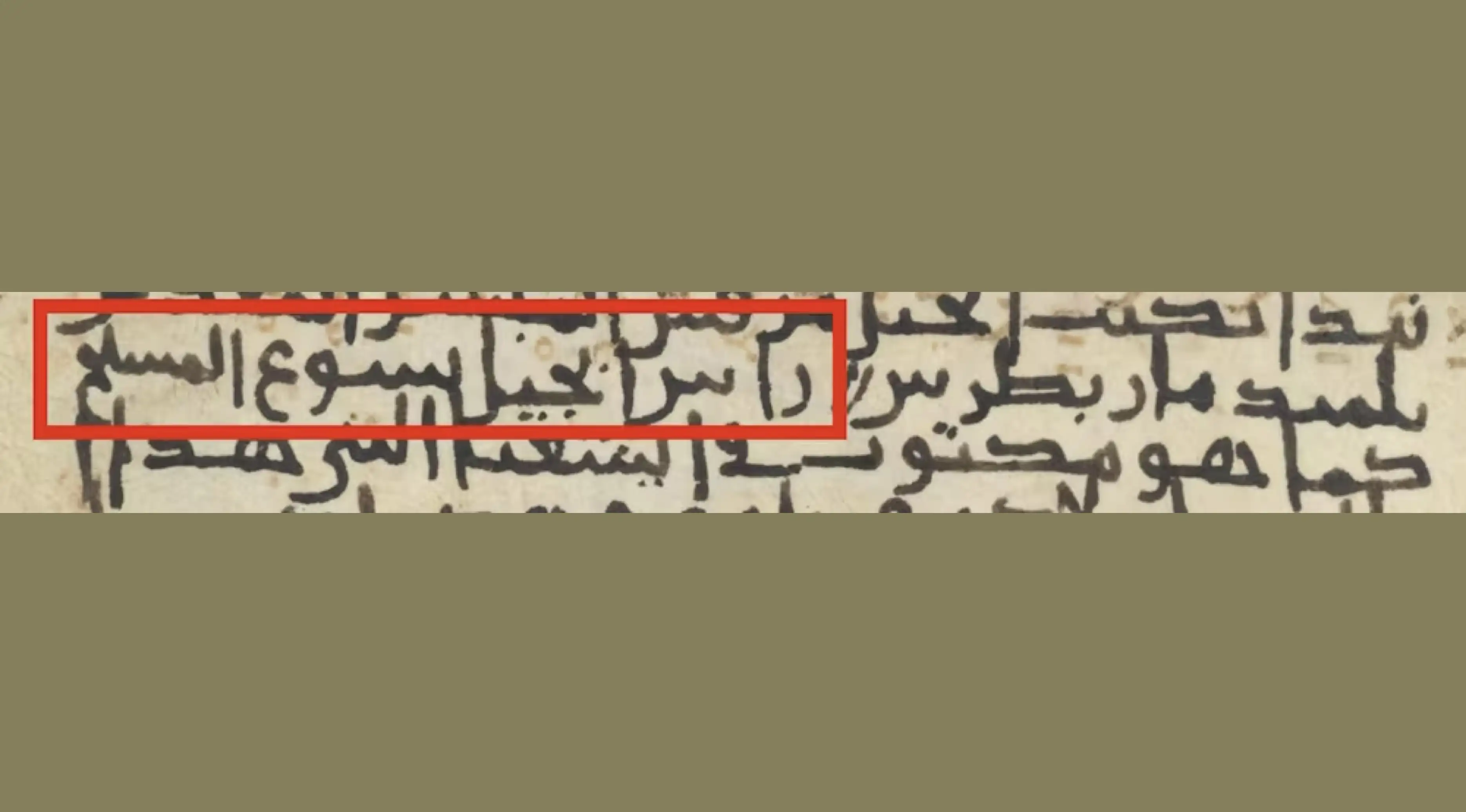

One important example comes from the very first verse of the Gospel of Mark.

Most biblical manuscripts begin: “The beginning of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God”.

But in a small number – including this Arabic translation – the words “Son of God” are missing.

It may seem like a small omission, but it’s one that raises big questions about how early Christian communities understood Jesus – and how their texts evolved over time.

Arts & Culture

Ancient teens were full of existential angst too

To understand where this Arabic translation fits in the broader manuscript tradition, I created a dataset of its variant readings and fed it into a phylogenetic analysis alongside hundreds of other Gospel manuscripts and translations.

Using a supercomputer at the University of Melbourne, the model evaluated millions of possible relationships between these texts, calculating how likely each one was based on the patterns of variation they shared.

What emerged was a textual family tree showing the most likely explanation of the evidence and how confident we are in the reconstruction.

The analysis showed that this Arabic translation belongs to a group of manuscripts known as the ‘Caesarean’ text-type' – a distinctive textual tradition thought to have circulated in the Near East during the first millennium.

Traditionally, scholars grouped New Testament manuscripts into three major text-types: Alexandrian (found in the earliest and most reliable Greek manuscripts), Western (found in early translations and church writers), and Byzantine (the text behind the King James Bible). The Caesarean text was proposed as a fourth.

The existence of the Caesarean text-type remains controversial.

But the phylogenetic results now offer strong evidence that these manuscripts are closely related. This Arabic translation turns out to be a crucial piece of that puzzle.

My hope is that research like mine will help shape future editions of the Greek New Testament, used by scholars and translators around the world.

Arts & Culture

The history of paper

But this area of work has implications beyond the Bible.

We can use the same techniques for any tradition shaped by scribes and copyists. At the moment, I am working with history researchers applying the same phylogenetics methods to the manuscripts of the Roman historian Livy.

The more precisely we can map how texts were copied and changed, the more clearly we can hear the voices of the ancient world – not as static monuments, but as living traditions shaped by human hands.

Dr Robert Turnbull’s book Codex Sinaiticus Arabicus and Its Family is published by Brill and available to buy online.