Send us baby food, board games - and some barmaids

New records are filling the gaps in the story of how Darwin Red Cross responded to the devastation of 1974’s Cyclone Tracy

Published 7 October 2015

Send baby clothes, bedding, unsweetened milk and “quiet” games. And plumbers. And barmaids.

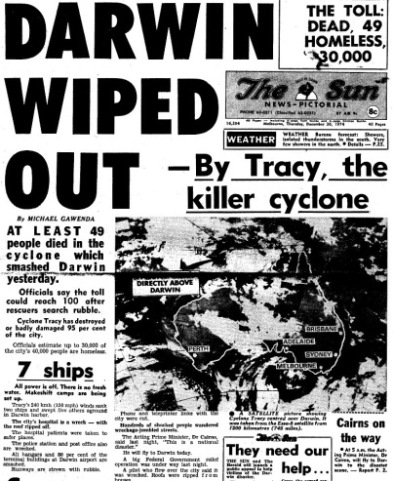

The pleas for help of any kind started soon after Darwin was flattened after Cyclone Tracy tore through the city on Christmas Eve in 1974, killing 71 people in terrifying winds that reached more than 200kmh.

Now a treasure trove of newly-released documents from the Red Cross reveals how the aid agency mobilised after one of Australia’s worst peace-time disasters, organising and sending supplies of every kind to help get the devastated city and the people back on its feet.

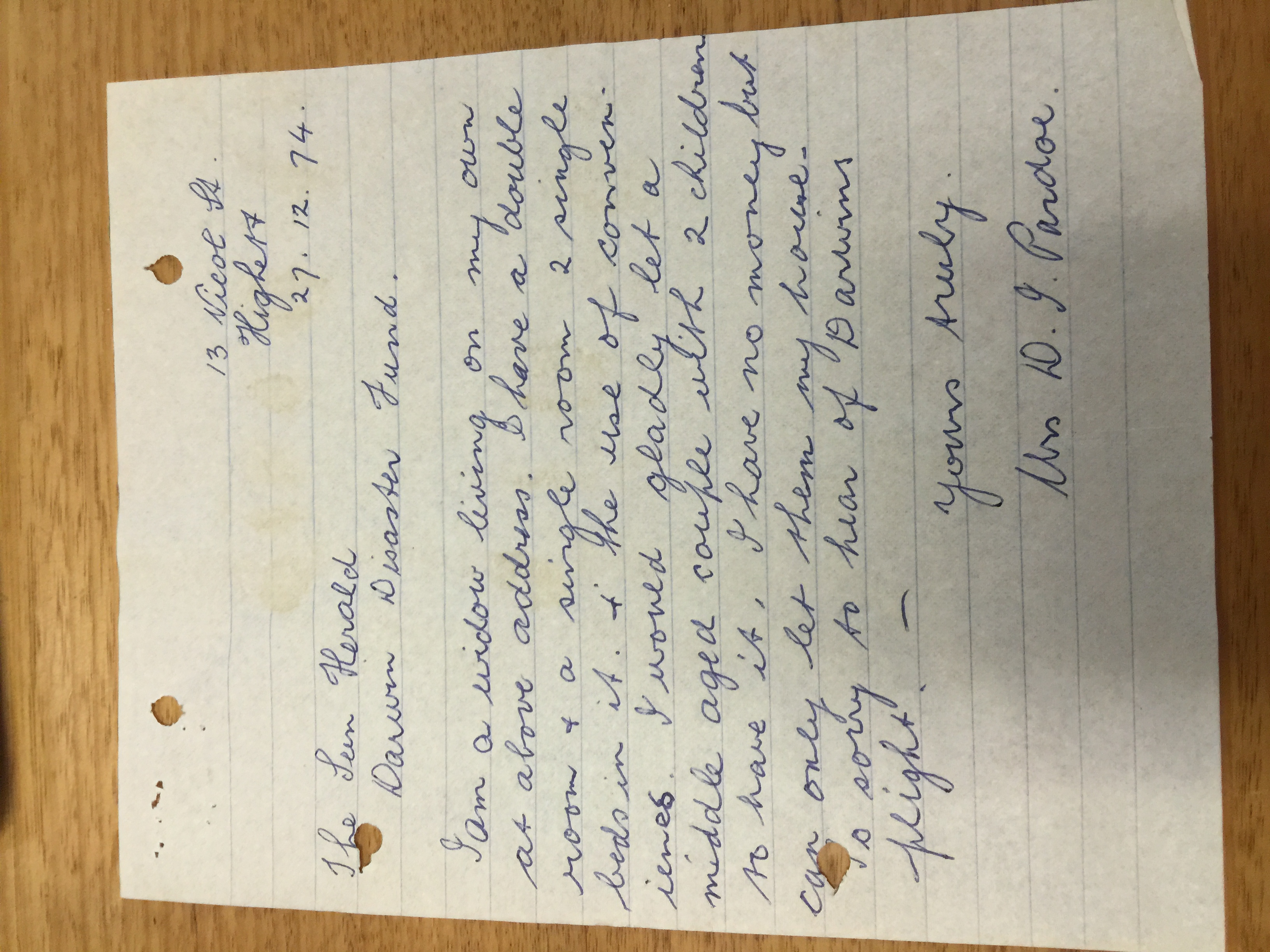

The letters, telexes and telegrams show Australians responded with typical compassion and generosity to the catastrophe, quickly answering urgent requests for food, water and clothing. In fact, correspondence shows that within weeks the Red Cross went from needing donations of clothing to pushing back on the huge volume of items concerned Australians were ready to part with.

The Australian Red Cross Centenary Archive was gifted to the University of Melbourne last year, and represents 100 years of activity, mostly relating to Australia’s war efforts, but also covering disasters such as Tracy.

The collection has been conserved and catalogued over the past year, and University of Melbourne Archivist Katie Wood says its 400 shelf metres of information is now accessible to the public and researchers, and sheds light on some of Tracy’s untold stories.

Common among urgent relief requests sent from Darwin Red Cross headquarters to their offices in Adelaide, Sydney, Melbourne, and Perth in the cyclone’s immediate aftermath was for unsweetened milk and baby food.

After the initial emergency had passed, baby clothes and children’s bedding, along with toys, were also on the list of required items, reflecting the population of very young families living in Australia’s northernmost city (then really a town) at the time.

On Christmas Eve 1974, with a population of 42,000 living in 12,000 homes, the small tropical city had something of the wild west about.

University of Melbourne historian Joy Damousi says at the time Darwin would not have been high in the consciousness of Australians outside the Territory.

“Knowledge of Darwin was largely related to World War 2, and its exposure to Japanese air attacks are what put the town on the map.

It was even then still very much a remote outpost, far, far away from the rest of Australia in a time before mass travel and cheap airfares.

Professor Damousi says rebuilding Darwin brought about major social change there, and some historians argue it transformed Darwin.

“The rebuilding of Darwin was a deliberate undertaking that really began the process of turning Australia’s attention toward Asia, and allowing it to develop as the cosmopolitan city it is today,” she says.

Houses in Darwin before Tracy were breezy, elevated affairs designed to deal with the challenges of tropical living before widespread air-conditioning was affordable or accessible, according to University of Melbourne Associate Professor of Urban Planning Alan March.

“In these houses, the main living areas were at first storey, while recreation, play and car storage areas were at ground level, maximising air movement to cool the house at night and to provide large areas under houses for activities and clothes drying during the long wet season.

“This form of tropical architecture remains the favoured configuration, but before rigorous building controls were in place, it left many structures built in the rapid expansion period of 1950 to 1973 unsuited to withstanding cyclones.”

Associate Professor March says one of the main challenges of cyclones is the dual risks of flying debris and upwards forces on roofs.

“Intuitively, we construct buildings so walls provide structural integrity against the force of gravity to roofs and upper storeys. The strength of Cyclone Tracy, recorded at 217 km/h at Darwin Airport just before the station failed, overcame the majority of homes’ ability to retain their roofs.

As winds passed over structures at high speeds the negative force created by the passage of air effectively peeled the roofs upwards off homes.

Once roofs were compromised, the integrity of the remaining structures was, in turn, significantly weakened. This left many houses partially intact, but without roofs and upper storey walls.

“Residents, unable to leave without power or light, sheltered in their homes as best they could, clinging perilously to the remains of their houses using whatever shelter was available during the night.

“Fortunately, the presence of a low tide at the peak of the storm meant that storm surge flooding, a very real possibility in the low lying coastal areas of Darwin, did not occur.”

And just as Tracy resulted in positive social benefits through rebuilding and re-orienting, the legacy of Tracy for building safety is a significant success story, according to Associate Professor March.

All structures built in cyclone prone areas are now required to be able to withstand the likely impacts of wind forces associated with a severe cyclone.

Cyclone prone areas in Australia extend over a vast distance, from Broome on the west coast, to northern New South Wales on the east.

“Building Code of Australia compliance means it’s unlikely that roofs can be damaged by high winds and that walls can be penetrated by flying debris. In addition, whole of government and community focussed risk management approaches that originated in the lessons learnt from Tracy have led to significantly improved preparations for cyclones over time.”

Notes from the 1974 annual report show Red Cross activities in Darwin before the cyclone had been mostly supportive, even “uneventful”, although it played a role in keeping the social fabric together.

Apart from the important task of operating the blood service, volunteers had staffed a kiosk and a little library at the hospital, presented small gifts to new mothers, offered hospitality to the refugees arriving by boat from Vietnam, organised play groups and child minding, and visited the elderly.

But a note to Australian Red Cross HQ from the Darwin office weeks into the aftermath of the disaster states: “Tracy changed all that”.

“After Cyclone Tracy, Red Cross suddenly came to life in the Territory,” the report’s author writes. “Teams of Red Cross staff and volunteers … streamed into Darwin to help organise what was to become the biggest relief operation in Australian history.

“At the same time, teams of staff and volunteers set up an Australia-wide tracing service so that members of families separated by this disaster could again make contact with each other.”

Apart from the obvious humanitarian aid offered, the tracing service that tracked movements of Darwin’s population after Tracy emerges as the most significant and long-term contribution the Red Cross made, making all the difference to fair funding to victims over the following few years of resettlement and rebuilding.

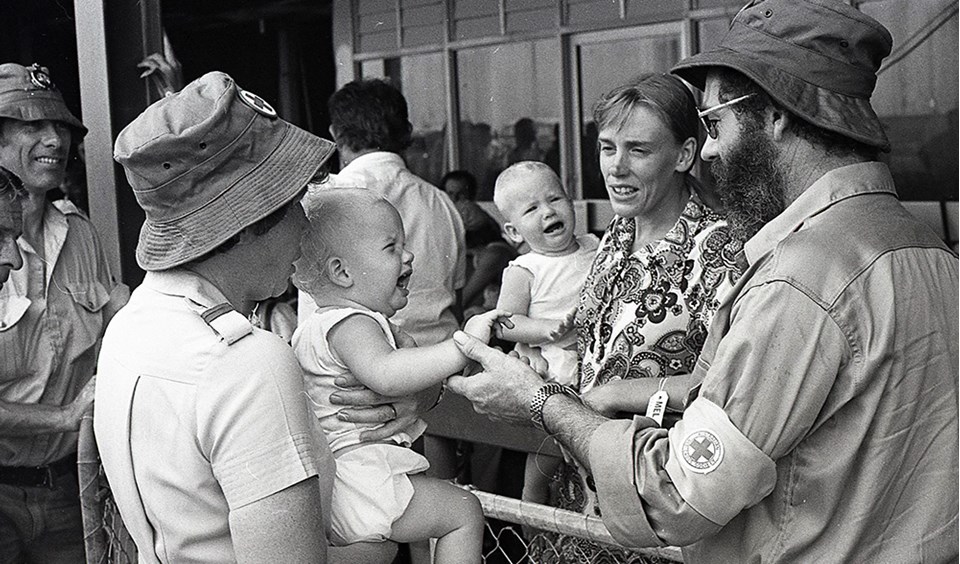

In the first 72 or so hours after the cyclone, 30,000 people were evacuated by air or road, often with only the clothes they had been wearing when Tracy struck.

Ten thousand people – mostly men – remained to begin the clean up and rebuild process. A note in a Red Cross review of their relief strategy some months later asks: “was it wise to so quickly evacuate the women and children, especially the women”, and you wonder what situation had prompted that particular doubt!

The role of the Red Cross quickly moved from providing spare clothes and something to eat to documenting in precise detail – one family to a page of lined notepad paper – who was leaving, what their Darwin address was, where they were going or who they’d be staying with, what they had been given to wear, what their family’s main source of income was, and how cash was to be supplied to them.

The task was huge, with a secondary, even huger spin-off role answering the tens of thousands of requests from worried family and friends elsewhere in Australia and around the world.

One of the reports mailed to Red Cross Australia HQ underscores the steady march of technology – it was all done by typewriter except for a lone computer.

“I am sure you will be interested to know that we have used a computer for the first time in handling the list of evacuees and we are now working with some experts in trying to develop a system which can improve the quality of this kind of service in future disasters,” the report notes. “We are happy to keep you informed on this project if you are interested.”

The computer was donated by Wang, and pops up occasionally in the documents as a thing of wonder, a bit of an experiment, the very special “print outs” (sadly not part of the archive) referred to with due deference.

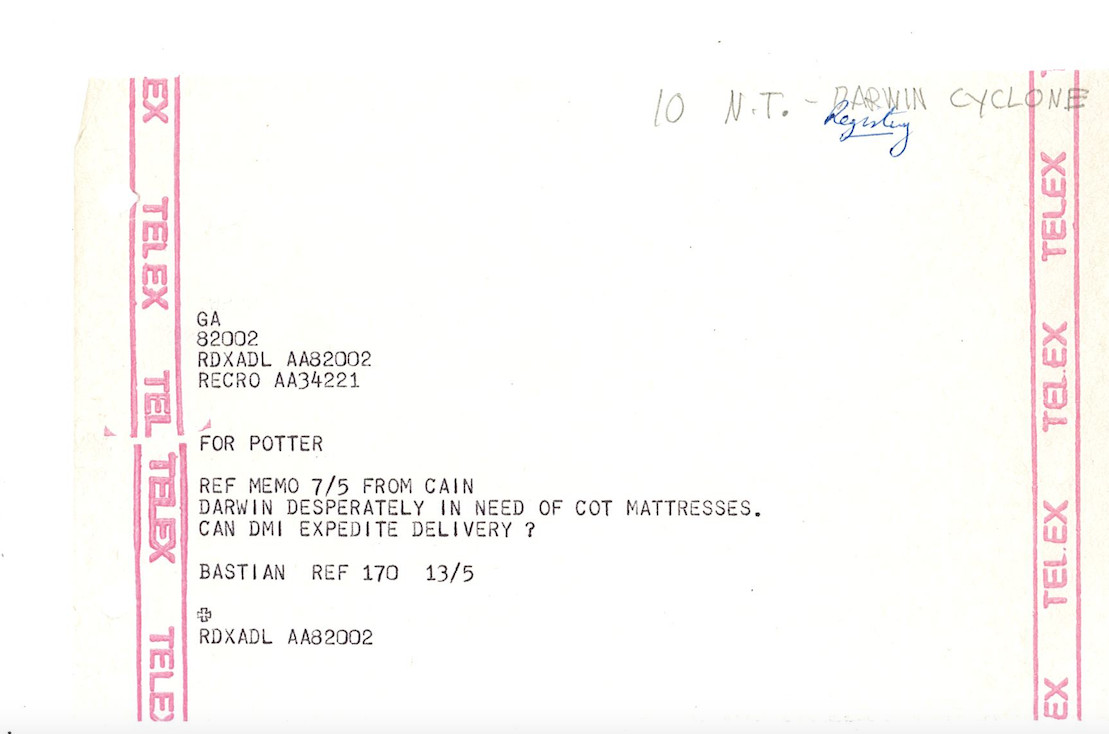

The primary means of urgent communication was telex, and the presumably less urgent letters in the archives are carbon copies, third impressions on tissuey yellow paper tapped out by skilled typists.

The few typos that creep into correspondence under the pressure of the early days are gone within a week.

Subsequent letters are dead accurate, polite, low-key, brief and responsive … with a few wry Aussie jokes and whinges about weather in post-script appearing as delicious gems for readers of the archive.

The initial post cyclone telex sent from Darwin to anyone listening out in the world is more than harrowing: “total devastation” is all that can be described. Melbourne’s Sun News-Pictorial newspaper went with “Darwin wiped out”.

The correspondence archive also contains a large number of telexes from Red Cross offices around the world commiserating and offering help, with heartfelt messages coming from near neighbours Timor, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea.

And then, down to work.

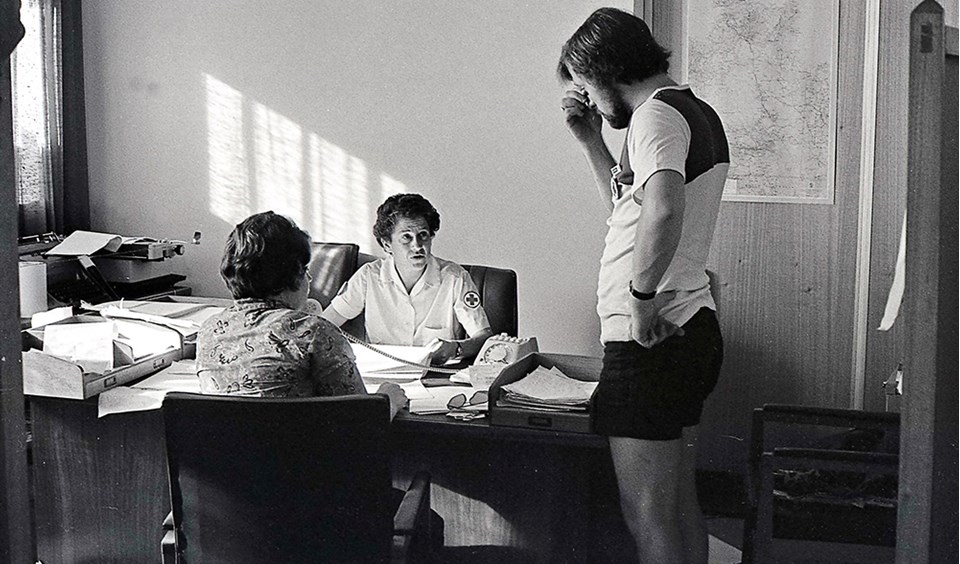

“Calm in a crisis” doesn’t quite describe Darwin Red Cross efforts over the days and weeks after Tracy, and the months later when committed Darwinians began to think about returning.

Staff are shown methodically “working the problem” of how to fix things for Darwin.

A significant amount of correspondence covers the need for mattresses of all sizes, but particularly cot mattresses, again highlighting the prevalence of young families in the population that was evacuated and accommodated in emergency shelters, some of whom eventually returned and needed furniture.

Difficulty in freighting quantities of mattresses, pillows and household linens are covered in detail, but bedding manufacturers Dunlopillo and Actil agreed to provide items in combination of donation and very competitive pricing (paid for by federal disaster relief funds). Such bulky items proved difficult to move around, however.

By July 1975, delays caused by government regulation of freighting are trying the patience of aid workers, as testy correspondence between the Red Cross and the Minister for the Northern Territory in Canberra reveals.

The resulting expedited delivery is celebrated, but to the “amazement” of those on the ground.

Emergency food arrived in Darwin immediately after the cyclone, with the first shipments leaving by military plane from Sydney on Christmas Day.

Kraft sent in quantities of Vegemite, peanut butter and processed cheese, and at the airport pies, pasties and sausage rolls were given to evacuees waiting for their place on the next plane out.

A cutlery shipment from Red Cross Adelaide was welcomed at Darwin HQ: “We now no longer have to make sandwiches with the handle of a spoon.”

Darwin HQ, a brick building that only took damage to the roof, appears to have been a significant base in the recovery effort, once a tarpaulin had been secured overhead. Food was prepared by volunteers for relief staff and anyone else who dropped by needing a feed.

The Secretary General of the Australian Red Cross, Leon Stubbings, visited Darwin with Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, and in a report on his visit he writes of a local Red Cross volunteer who had been making food and using her own car to provide meals on wheels to 12 “obviously courageous and somewhat stubborn elderly folk who refused to budge!”

A daily ration of 2.5 cans of beer for each worker in the relief efforts is recorded, which looks to have been too hard an ask, leading to a sheepish enquiry about where on the books they should account for the extra half a can in excess of their ration the workers consumed.

There’s also a sequence of notes debating a soup problem.

Campbell’s had generously donated 105 cartons each of tomato and beef soup, not quite thinking through the clean water, can-openers, saucepans and stovetops connected to a fuel source needed to prepare it. It was taking up too much space in the Brunswick store in Melbourne and needed to be disposed of, but without giving offence to donors. After a flutter of diplomatically worded notes, permission was finally given for the soup to be given to Melbourne’s needy.

Donations of all sorts of toys are documented through the correspondence, with two crates even being collected by elementary school children in New York State.

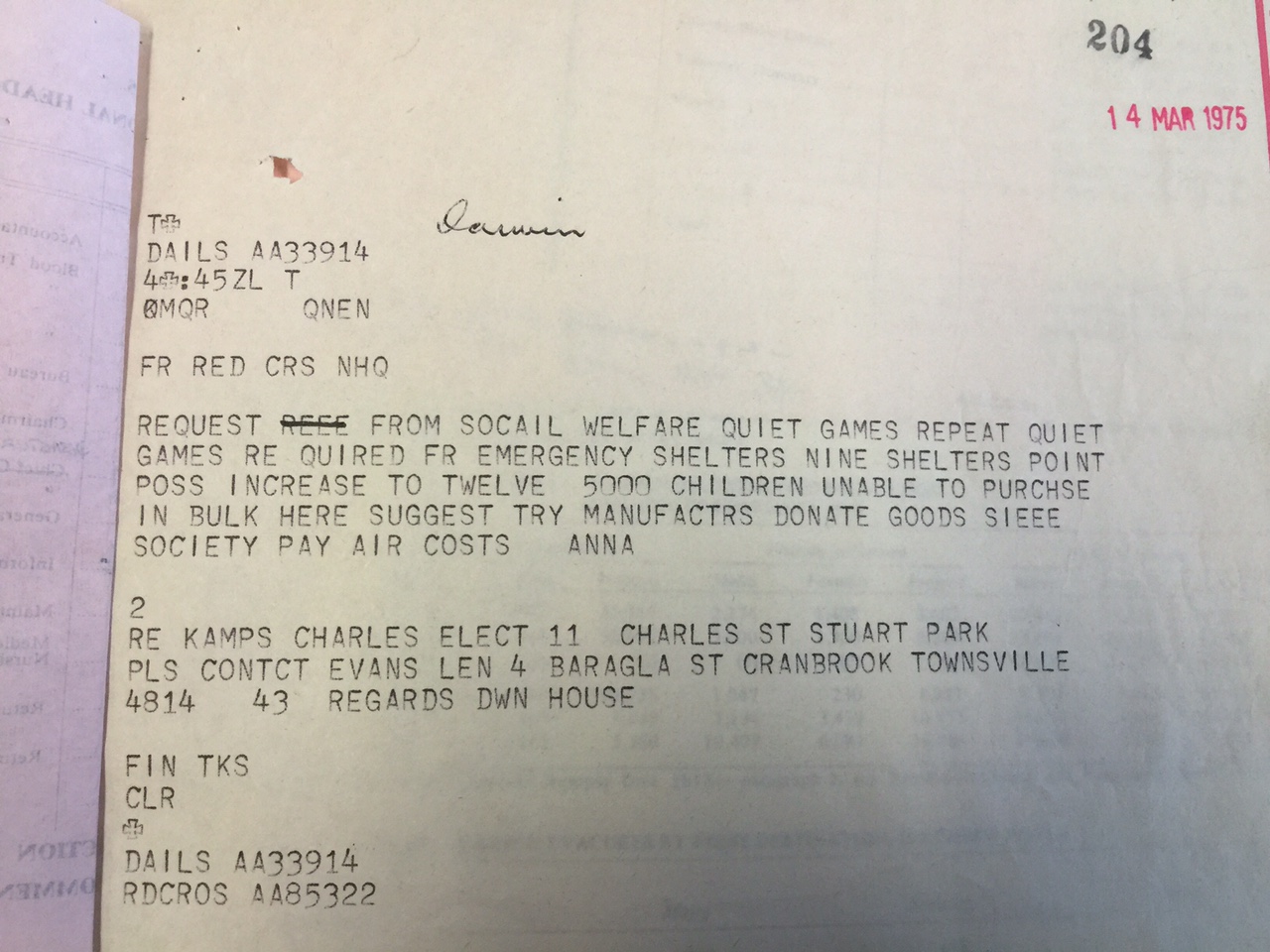

In March, though, “quiet games, repeat quiet games” for use in evacuation shelters were being requested, reflecting the all too close accommodations of those living under tarpaulins and in caravans in Alice Springs, waiting on the all clear to return.

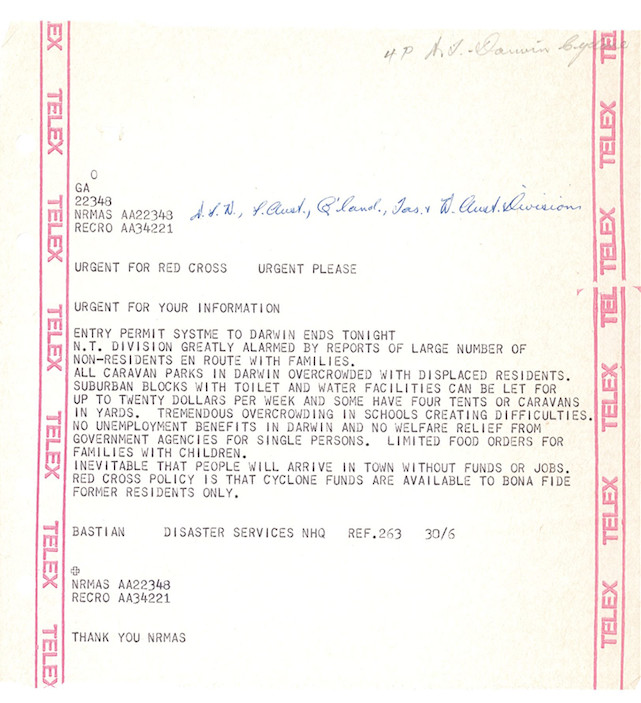

Unfortunately not every Aussie responded with goodwill. A darker side to Australians’ response to disaster emerges, with Red Cross alerting authorities to the need for tight scrutiny of people re-entering Darwin after the all clear for return was given.

It seemed people from elsewhere in Australia were turning up in significant numbers, hoping for a share of the cash and goods that was being supplied to bona fide returnees, necessitating road blocks and identity checks.

Unqualified job-seekers were also a drain on resources, showing up on spec hoping to find work, but only compounding the problem.

One (unnamed) gouging GP gets special mention for charging $25 (equivalent to more than $180 in today’s dollars) to administer typhoid vaccinations to remaining residents, relief and rebuild workers – necessary because of the unsanitary water and food rotting in fridges.

By Christmas 1975, the town was getting back on its feet. It still needed help though, and a telex south seeking workers provides a snapshot of mid seventies Darwin society: “Request for male skills in building trades required as plumbers, plasterers, electricians, building. Female skills as stenographers, typists, shop assistants, barmaids.”

Darwin was returning to a state of normality, and embracing the opportunity to reinvent itself after Australia’s worst-ever weather event.

The University of Melbourne Archives were established in July 1960, to collect and preserve records relating to the University and to business and business people for the purposes of historical research. Today it is one of the largest non-government archives in Australia, with a collection of nearly 20km of records, and is custodian of a wide range of professional, community, women’s, peace and political organisations’ records.

Banner image: Three year old Poppy Magoulis rides a tricycle through the ruin of Darwin. Picture: Bruce Howard, News Corporation Australia.