Sciences & Technology

Celebrating the “grandmother” of optimisation on International Women in Maths Day

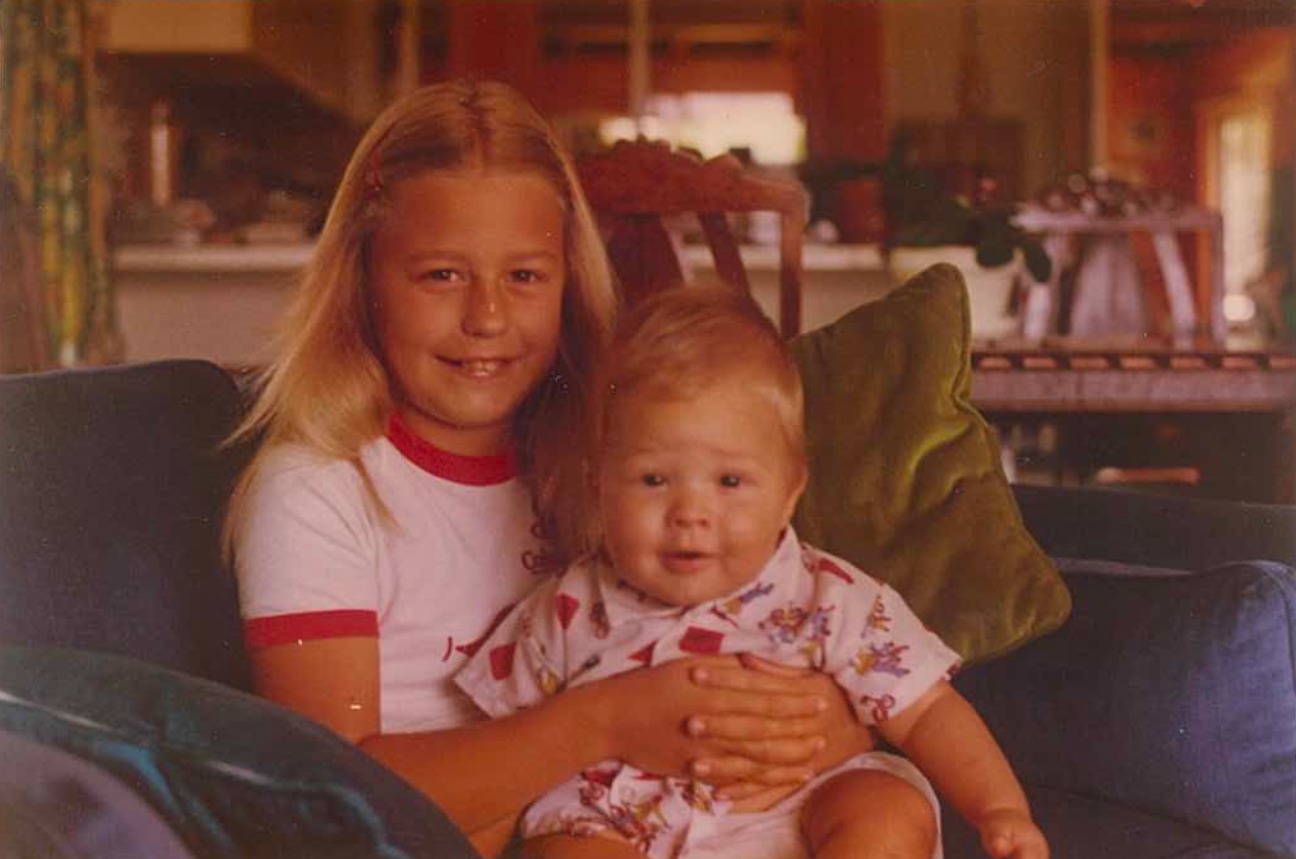

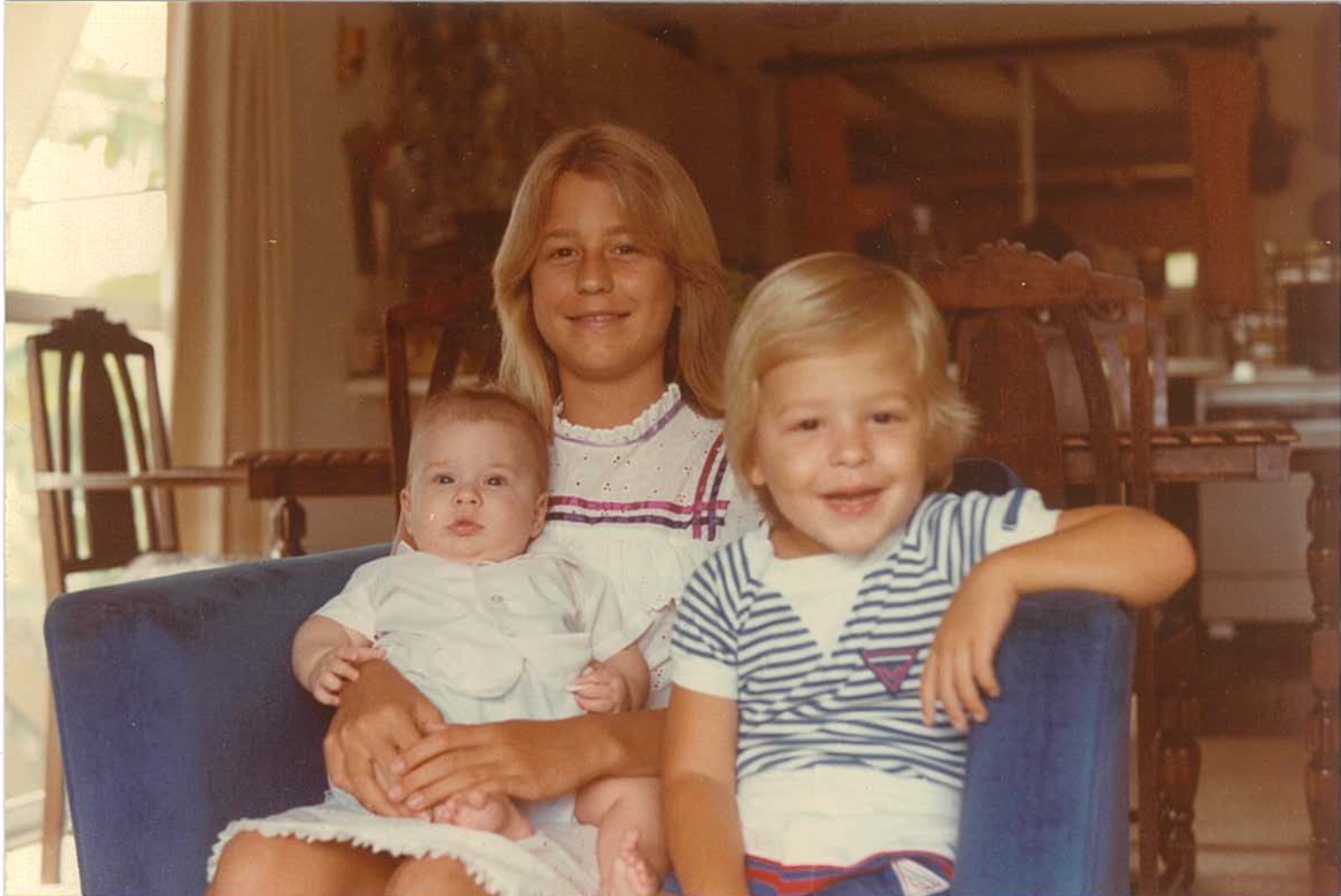

Chemical biologist Professor Megan Maher and her zoologist brother Dr Tyrone Lavery hope to one day combine their fields of study and solve new research puzzles together

Published 21 May 2025

Growing up on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast, brother and sister Megan and Tyrone spent a lot of time outdoors exploring nature. Now, they both research and teach at the University of Melbourne’s Faculty of Science.

We asked them how they developed a shared passion for science, how they mentor students and their aspiration to work together in the future.

Megan: I work at the molecular level of life, where biology meets chemistry, while my brother Ty works at the macro level, studying animals and ecosystems.

My research looks at the biological roles of transition metals – the elements in the middle of the periodic table, including copper, manganese and zinc.

We might think these metals are lifeless, but they are essential nutrients for lifeforms from bacteria to humans – but we don’t fully understand what they do.

Tyrone: I’m a mammalogist interested in how species are distributed and related, how they interact with their environments and how we can conserve threatened species.

I particularly love finding and studying incredibly rare mammals, like the Vangunu giant rat.

To do this, I often work with Indigenous people in Australia and the Pacific, complementing their deep local knowledge with other scientific practices, helping to develop conservation plans and protect habitat from mining or logging.

I’m also the Director of the University of Melbourne’s Tiegs Museum, which has a weird and wonderful collection of zoological specimens.

Sciences & Technology

Celebrating the “grandmother” of optimisation on International Women in Maths Day

Megan: Ty was always going to be an ecologist. When he was little, it took forever to walk with him to the local shops because he stopped to study all the bugs and birds on the way.

I left home for university when Ty was seven, so we didn’t spend much time living together, but we’ve always had a good relationship despite our ten-year age gap.

These days, we hang out a lot because it’s only a short walk between our houses, which is lovely.

Tyrone: I was an active kid and loved being out in nature. My football coach would tease me about how long it took me to run a lap around the oval because I was looking for insects in the grass.

My younger brother Rhys and I were lucky to grow up on six acres with a forest and a creek on the Sunshine Coast.

I remember being excited when Megan got her driver’s licence because it meant she could take us to the beach. When I was nine, my dad took me on a camping trip up to the Gulf of Carpentaria and across Cape York.

Spending time in those wild places had a big impact on me.

Megan: Our parents encouraged us to do whatever we enjoyed, regardless of gendered assumptions, which was unusual for their generation.

In high school, I played clarinet and guitar and planned to audition for the Queensland Conservatorium of Music.

At the last minute, realising I preferred physics and chemistry, I opted for a science degree instead.

Tyrone: I did a science degree too, focusing on zoology and ecology. After graduating, I worked as an environmental consultant for a few years before returning to do my PhD on the mammals of northern Melanesia at the University of Queensland.

I worked at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, the University of Kansas and the Australian National University in Canberra. I joined the University of Melbourne in 2023.

It would be great to find a project where Megan and I could collaborate.

We’ve been talking about this for a while and need someone to bridge the gap between Megan’s biochemistry and my zoology.

Sciences & Technology

First ever images captured of rare giant coconut cracking rat

Megan: After the second year of my degree, I was offered a year’s work placement with Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) in Melbourne.

Though our family moved to Queensland when I was two, I was interested in eventually coming back to Melbourne.

I had a great time and made a bunch of friends. After finishing my third year in Brisbane, I came to the University of Melbourne for my Honours year and PhD in Inorganic Chemistry.

I have moved between the University of Sydney, Imperial College London and La Trobe University, but returned to this university in 2019.

I was so thrilled when Ty found employment here too.

Tyrone: Zoologist and environmentalist Professor Tim Flannery was a big inspiration for me. When I read his book Throwim Way Leg (New Guinea Pidgin English meaning ‘to go on a journey’), about working with Indigenous people in New Guinea, finding species of mammals previously unknown to western science.

I thought “That's what I want to do” and learnt how to speak Pidgin.

Seeing Megan’s positive experiences in academia also influenced the choices I made in my career.

Megan: A scientist I admire is Professor Jenny Martin, a leading expert in protein structure and X-ray crystallography (a technique that I use).

She is also an incredible supporter and mentor of women in science.

When you use X-ray crystallography to study a protein, you get an electron density map. It’s like interpreting a jigsaw puzzle where you build the atoms in one by one to see the protein structure.

Another role model is structural biologist Professor Mitchell Guss, who helped me to solve the structures of some proteins I was studying for my PhD.

Back then, this involved wearing 3D goggles while looking at the protein structures on a computer screen.

It felt as if I had shrunk inside the protein molecule and could reach out to touch its component atoms.

These days, I simply rotate a 3D computer model on the screen of my laptop to examine it. It’s more efficient but lacks the magic of the old, more immersive technique.

Sciences & Technology

Diverse role models and mentors are helping women in STEM succeed

Tyrone: Both of us love the detective work of being a scientist. I’m always looking for clues, not just when I’m tracking down a rare or ‘new’ species, but also to figure out how species are related, how they interact with each other and their environment, whether their numbers are dropping, what’s threatening them and what we can do about those threats.

This can involve interviewing the local people about what they’ve seen, heard or found, digging through historical records, field work with camera traps and other techniques.

It’s often so much fun that it doesn’t feel like work to me.

Megan: There are endless puzzles to solve in science. By analysing the structure of proteins, I’m figuring out how they use metals or manage their concentrations in biological systems.

A simple example is the haemoglobin protein in your red blood cells that uses iron to transport oxygen around your body.

If we lack iron, we become anaemic.

An emerging area of research is exploring how metals are involved in infection and immunity, and how they can work as natural antibacterials in your body. This could inform the development of new antibiotic drugs.

I like the more abstract nature of my work, whereas Ty likes to get his hands dirty.

Tyrone: I like working outdoors, going barefoot and sleeping under the stars, or under some big leaves if it’s raining.

I have had some scary moments in the field, including some encounters with giant centipedes and getting temporarily lost at sea during a storm in the Solomon Islands.

Fortunately, the local people are incredible navigators, so they steered us safely back to land.

I’m in awe of Indigenous peoples, how they understand and interact with nature, how they can leave home with just a machete and find food and water or build a shelter without a worry in the world.

Megan: I use the Australian Synchrotron in my experiments, a huge piece of shared research infrastructure.

I use its beams of X-rays to determine protein structures from their X-ray diffraction patterns.

The synchrotron is in high demand, so you only get a short time slot to collect your data, which can be any time of the day or night.

My friends laugh when I tell them I’m unavailable because it’s my ‘beam time’. Amazingly, you can drive this enormous instrument remotely from your laptop.

Health & Medicine

Starving the bacterium that causes pneumonia

Tyrone: As well as research, we both enjoy teaching and mentoring students. I like spending time in the field with students because I get to know them well. Sometimes I bring my family on field trips too.

I have a student working in North Queensland, and my daughter helped him put his camera traps out, which was a great experience for her.

The work-life balance and integration have been generally good for me and my family.

Megan: Being a woman in one of the so-called ‘hard’ sciences traditionally dominated by men, teaching and mentoring young women in this field is important to me.

I want to leave a legacy of supporting women in this area of science.

Key to that is achieving a balance between multiple competing demands like family and work, which isn’t easy but can come with persistence and time.

I am lucky to feel excited every day about coming to the lab because I enjoy the creativity and discoveries of my work.

– As told to Rebecca Colless