Skydiving for science

A group of scientists investigating nanoparticles wanted to conduct an experiment in low gravity, so they decided to do it while free falling. See what happens next.

Published 5 July 2016

At 14,000 feet above Melbourne three scientists wait anxiously for the signal to jump, their arms crossed protectively across their chests, a modified plastic syringe in each hand, the plane engines and wind roaring around them.

This is extreme do it yourself science.

As soon as their tandem instructor jumps out with them, each must keep the presence of mind to push down on the syringes they are holding to release metal and organic particles into a solution where they will mix and form crystals in the temporary low-gravity generated by free-falling.

Then they must hold on for dear science.

A team of material scientists from the University of Melbourne and the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) has shown for the first time how gravity influences the formation of crystals in Metal-Organic Frameworks.

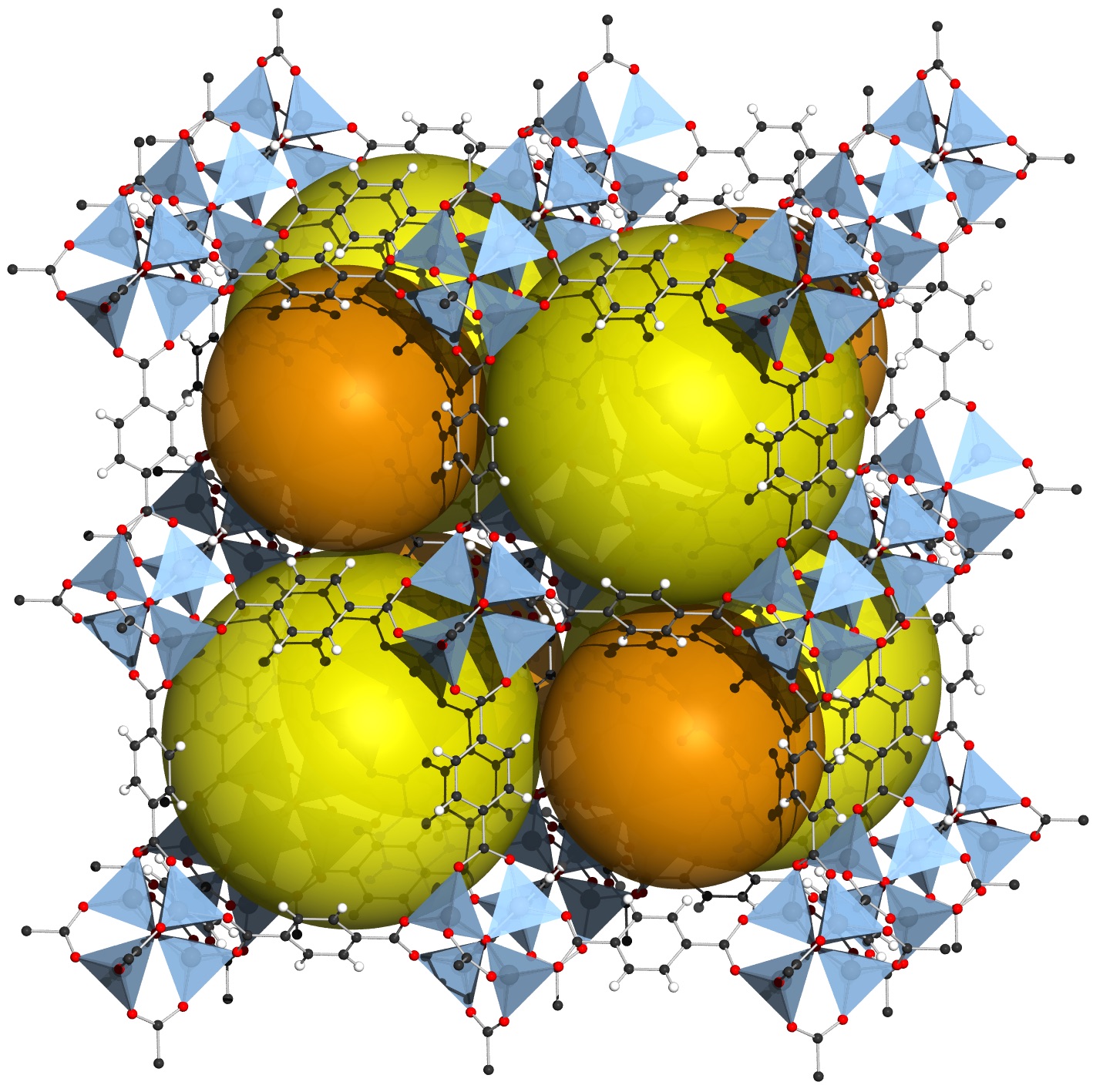

These are nano-sized synthetic structures riddled with molecular holes that are at the forefront of materials science. Their huge surface areas – a teaspoon of MOF can have the same surface area a football field – offer a host of potential applications from storing greenhouse gas emissions and concentrating gases to power cars, to protecting sensitive therapeutic drugs that couldn’t otherwise survive in our bodies.

“There are various ways we can alter the structure of MOF crystals to design new applications, such as using temperature, using water, adding alcohol or adding soap. Now we can add another tool for designing MOFs – gravity,” says materials scientist Dr Joseph Richardson, of the CSIRO who has led the research that has now been published in the European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry.

“We now understand more about how MOFs crystals form and the mechanisms at work, which can now help us in designing new and better MOFs,” says co-author Mattias Bjornmalm, a PhD student at the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at the University of Melbourne and one of the skydiving volunteers.

How they did it is a story not of high-tech equipment and labs, but of using whatever materials the team could scrounge.

Gravity has been shown to influence the formation of many crystal structures, but what Dr Richardson and his colleagues wanted to know was whether gravity could affect the formation MOF crystals. Generating a high-gravity environment was relatively straightforward and involved using centrifuges to spin samples. But short of hiring out the International Space Station, experimenting in a low gravity environment was a much tougher task.

Initially they tried dropping the tubes of solution and particles from a ten-storey building. They measured the low gravity free fall by using the in-built accelerometer sensors in their mobile phones. These sensors tell the phone when it is being tilted, but can also be used to measure acceleration as the phone falls. It meant wrapping their phones in foam and dropping them off the building. Easy.

They were able to successfully generate 1-3 seconds of low gravity, but that produced only an inconclusive influence on crystal formation. They needed to generate at least 10-20 seconds of low gravity for the experiment to really work. They thought about dropping the plastic tubes from drones or from a hot air balloon, but they calculated that they would only be able to generate about four seconds of low gravity. And in the case of the drone they would also have to come up with a complicated system to ensure the particles began mixing at the right time.

The logical solution was to jump out of plane while holding the syringes and do the experiment themselves.

And because they needed to be able to replicate the experiment several volunteers would be needed to jump. When Dr Richardson put out the call for volunteers, three of his colleagues were quick to put up their hands and pay for the jump themselves. Only one of the three, fellow PhD student Matthew Faria, had ever skydived before. The third volunteer was Dr Fabio Lisi from the School of Chemistry. Each carried several samples contained in special homemade syringes.

“It sounds a bit crazy but it was simply a logical progression in our thinking given the resources available to us,” says Mr Bjornmalm.

“We knew we only had one shot at this because skydiving is expensive, and at the time we didn’t know whether it would be too difficult or not to hold onto the samples during the jump,” says Mr Faria.

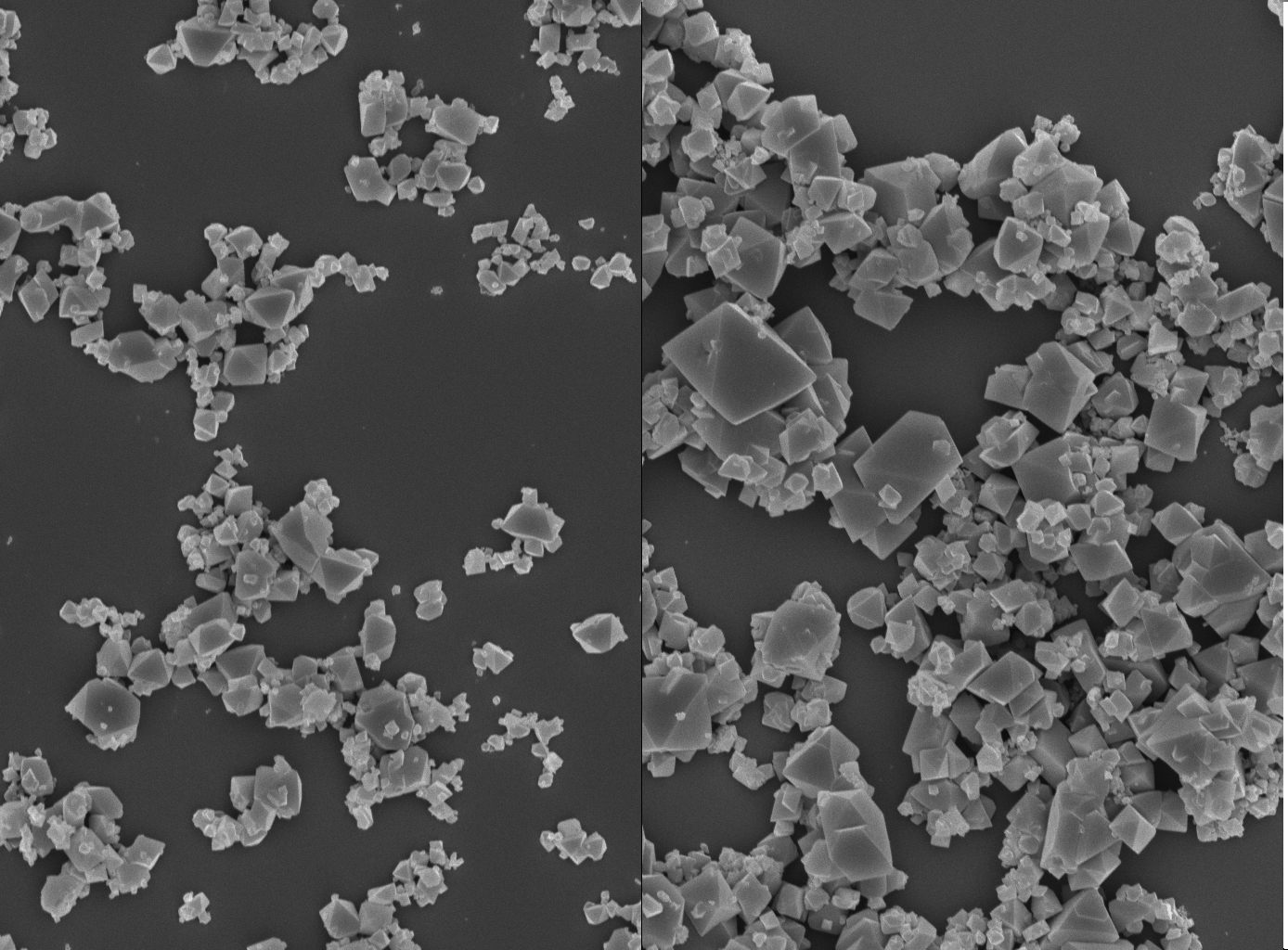

In the event they were lucky there were three of them because several of the samples broke up prematurely. But it all paid off. Fellow PhD student Junling Guo was waiting on the ground and rushed the samples to a portable centrifuge in the back of a car where the samples were “rinsed” to stabilise the crystal growth for measurement. The final results proved that high gravitation causes smaller MOF crystals to form and that at low gravity the crystals are larger.

The jumpers had all been nervous about parachuting, but like true scientists the fear of the experiment backfiring was greater than the fear of jumping out of the plane.

“I was definitely nervous, but I was more afraid that none of the samples would work out,” says Mr Bjornmalm.

Last year prestigious scientific journal Nature reported that MOF research had reached the point where commercial applications are poised to become a reality. MOFs act like sponges in being able absorb, or hold, other molecules inside their intricate crystal structures, but it is only in recent years that researchers have made MOFs strong enough to be reliable.

They could be used to extract greenhouse gases from fossil fuels, and they have the potential to be a more efficient way of storing hydrogen for electricity generation, replacing high-pressure tanks. The massive surface areas of MOFs means they could be used as catalysts, making all sorts of chemical reactions more efficient.

The group is particularly interested in the pharmacological applications of MOFs that could help in designing drugs. And in the complex and intricate field of drug design the smaller the MOFs the better, which means there is likely to be clear value in using gravity in centrifuges in developing new MOFs.

The application of using low gravity to produce larger crystals is less obvious and more practically challenging. But simply knowing how low gravity influences crystal formation is important fundamental knowledge that may in the future be useful. “The more we know about the fundamental mechanisms at work here, the better,” says Mr Bjornmalm.

And it was fun. Having lived to tell the tale all the researchers couldn’t resist inserting a joke about their methodology in the final journal article.

“Prolonged periods of low gravity were generated by skydiving out of an airplane with the use of a parachute to minimise the gravitational challenges after free-fall,” they wrote.

The other co-authors of the paper are Dr Kang Liang of CSIRO and Professor Paolo Falcaro, now at the Institute of Physical and Theoretical Chemistry at the Graz University of Technology in Austria.

Banner Image: University of Melbourne’s Mattias Bjornmalm falls through the sky holding a syringe in which nanomaterial crystals are forming at low gravity. Picture: University of Melbourne.