Stepping into the future

An ingenious rehabilitation facility merges cutting-edge technology with medicine to speed up recovery for amputees and stroke victims.

Published 7 October 2015

Next January marks two years since Zoe Creelman lost her left foot in a freak boating accident. It is also the month she plans to finish a five-kilometre run.

Zoe, now 25, was enjoying a sunny day with friends on the Port Hacking River near Sydney, when a wave tipped the boat. She fell beneath the bow and became tangled in the propeller as she emerged out the other end.

The next three months were a blur of surgeons, doctors, operations and hospitals as she came to terms with her loss.

“I spent two weeks in hospital in Sydney then came to the Royal Melbourne Hospital for another operation and to start rehabilitation,” Zoe says. “This isn’t what I expected but honestly, I am lucky to be alive.”

Her leg was amputated just below the knee and a prosthetic fitted. It has been a slow, but successful, recovery.

It’s taken a while, but I’m back to doing the things I enjoy, running and cycling and climbing and hiking. My quality of life is good.

This week, Zoe was one of the first in Australia to use a high-tech laboratory that will revolutionise care and recovery for thousands of patients just like her. She will use the technology over the coming months to assess her movements so she can get a new prosthesis fitted.

The Australian-first Neuromuscular Research Laboratory (MOVE Lab) is a partnership between the University of Melbourne’s Engineering and Medicine Departments and the Royal Melbourne Hospital.

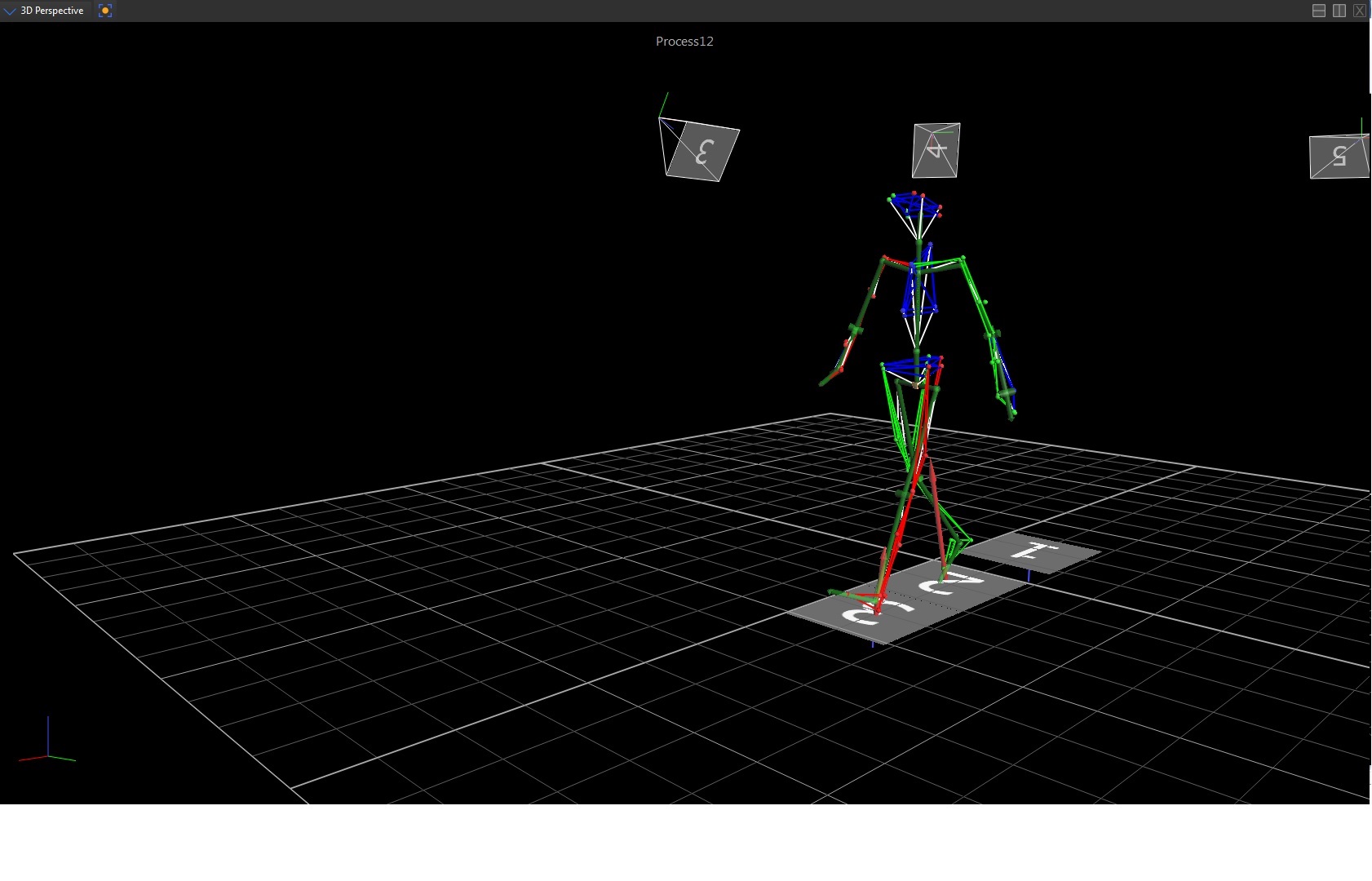

It is equipped to map the subtle nuances of human movement, using 3D motion capture, force and inertial sensors.

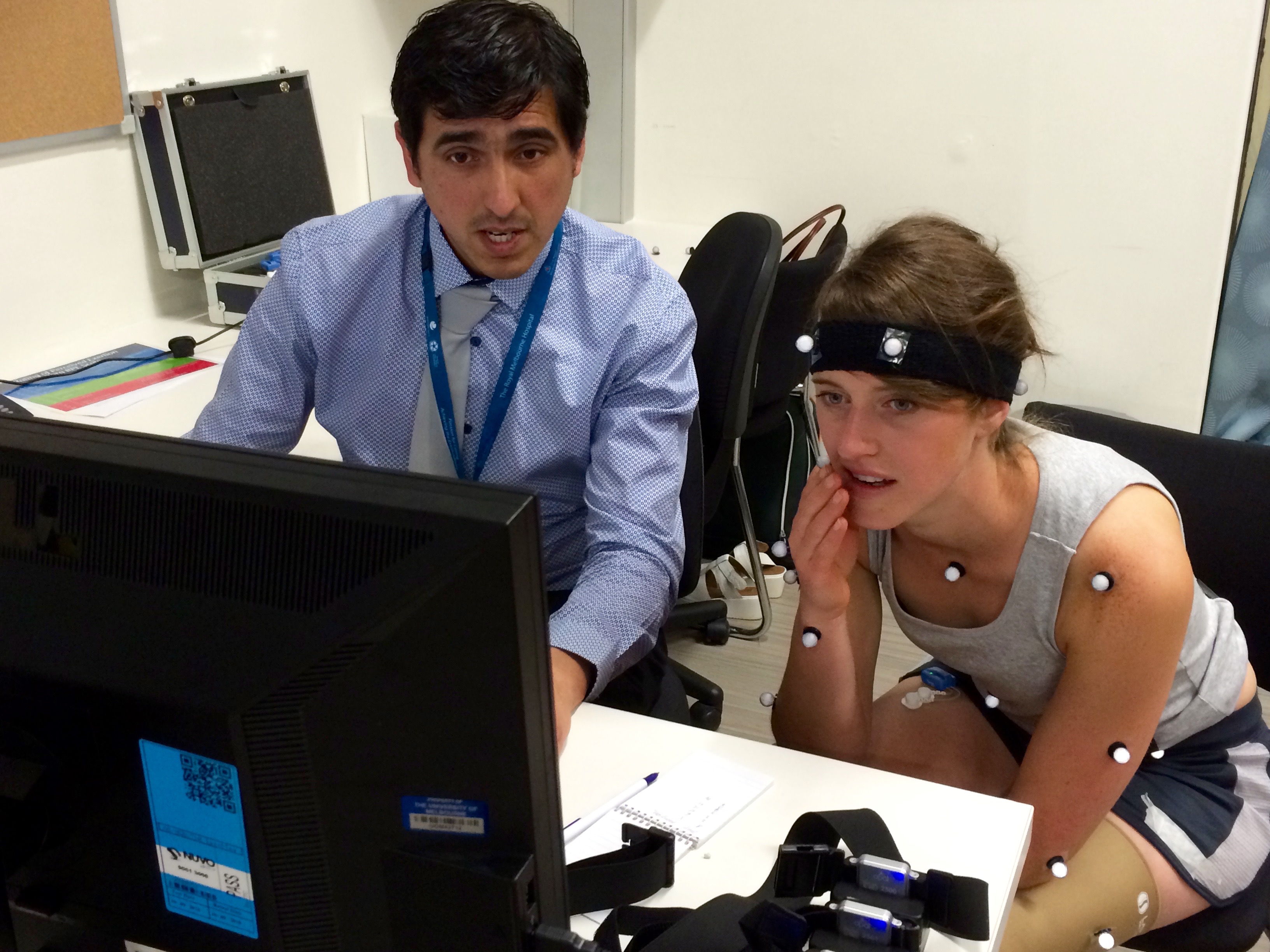

The patient is fitted with dozens of spherical sensors, from head to toe. They then move across a platform that detects minute shifts in weight and pressure.

This data is fed into a sophisticated computer program that tells the treating clinician precisely where the stresses are on the body, how the muscles are moving and which muscles are taking the most weight and pressure.

The Victorian Government also invested $75,000 for a Cometa Wave Plus EMG, a wireless device that monitors movement of patients’ hands and legs.

“It’s fascinating,” Zoe says, trying the technology the first time. “You can focus in on how much force individual joints are experiencing and phases of the gait as well.

“I am super impressed with it. This will be a very valuable tool for research and patient treatment, to help them progress and improve their quality of life.”

Currently, clinicians rely on visual observation of movement and a limited range of clinical tools to determine the mechanisms of movement disorders.

Director of Rehabilitation at The Royal Melbourne Hospital and University of Melbourne Professor Fary Khan says in the last decade, there has been increasing demand for medical rehabilitation services across the state and the country.

The MOVE Lab, housed in the Royal Melbourne Hospital’s Royal Park Campus, will benefit people recovering from stroke, or those with Multiple Sclerosis, tumours, amputees, cancer survivors and anyone who needs complicated physical care.

“It is always important to treat patients efficiently. With this lab, we can now see more patients, assess problems earlier on and target their therapy,” she says.

“Amputees, for example, may have a prosthesis fitted and while their treating professionals can do the normal assessments, sometimes that information isn’t precise.

“We can now pinpoint, fine-tune and adjust the prosthesis so that the balance is perfect. This is cost-effective, it’s efficient and it saves time.”

She says the Lab will also help doctors diagnose Multiple Sclerosis in the early stages, when the changes are slight and it can be overlooked by conventional assessments.

“We’re talking about very early intervention with this technology and this has a direct impact on a patient’s care,” Prof Khan adds.

“They get feedback about their progress and can see the progress they have made.”

University of Melbourne Department of Medicine Professor Mary Galea says the technology will drastically improve recovery time for patients.

“Three dimensional analysis is very useful when someone requires very complex care. We can then discuss the data with clinicians and develop a therapeutic plan specifically targeted to that patient’s needs,” Professor Galea says.

“In the case of an amputation, we can make very precise adjustments to a prosthesis that might be unbalanced or even slightly wobbly, putting pressure on other parts of the body. This technology can pick up those nuances and that can really make a huge difference to the patient.”

She said the next steps for the research team are to create portable sensors a patient can use out of hospital, to give them information about how the person moves at home or out on the street.

Professor Peter Vee Sin Lee of the Department of Mechanical Engineering, said this technology allows researchers to predict muscle and joint forces, which have until now been invisible.

“You can’t measure muscles and joint forces directly, because it’s too invasive. Musculoskeletal modelling using motion capture systems collect movement data to help us predict what will happen to the muscles and the joints when different forces are applied,” he said.

“This lab is unique because it’s sitting in a hospital. This allows us to work directly with the clinicians, the patients and volunteers.”

Victoria’s State Health Minister, Jill Hennessy, said the Lab represents an increasing shift towards personalised, streamlined and cost-effective medicine.

“This Movement Lab offers a great opportunity to improve the quality of life for so many Victorians.

This is what happens when we get specialists working together to create a personalised response. It’s the future of medicine.

And for patients like Zoe, the lab means a chance at getting on the path to achieving their goals faster than ever before.

“It’s really encouraging to see just how advanced this technology is. It can give you hope that you’re not going to be stuck in a wheelchair for the rest of your life,” she says.

“It’s nice to know this technology is there to support you to push your limits and advance towards reaching your goals.”