Health & Medicine

The future of Australia's doctors

Cracking down on repeat prescriptions is just one of a range of actions needed to restrict the overuse of antibiotics

Published 14 July 2019

The inappropriate use of antibiotics and other antimicrobial drugs in Australia is continuing to fuel a growing crisis of drug-resistant infections.

And reports that the Federal Government is moving to crack down on unnecessary prescription repeats indicate that it’s willing to take steps to address the problem.

But a far broader package of policy interventions is needed to help manage and contain the problem of drug-resistant infections.

For example, research at the National Centre for Antimicrobial Stewardship (NCAS), based at the University of Melbourne, Royal Melbourne Hospital and Monash University, has found that many GPs simply don’t have access to key guidelines, which require paid subscriptions.

“The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) Standards indicate that the use of guidelines, like the Therapeutic Guidelines, is considered standard practice. But in one of our pilot studies, one quarter of practices didn’t have access to them,” says Dr Jo-Anne Manski-Nankervis, a general practitioner and researcher at the University of Melbourne’s Department of General Practice.

Health & Medicine

The future of Australia's doctors

“Any barriers to their accessibility and use must be explored and remedied.”

Dr Manski-Nankervis says guidelines could also be better integrated into the clinical workflow.

“Our qualitative work has identified that GPs want computerised decision-support incorporating guidelines integrated with electronic medical records in a way that fits within the clinical workflow. So, we are co-designing clinical decision-support tools with GPs to try to address this gap.”

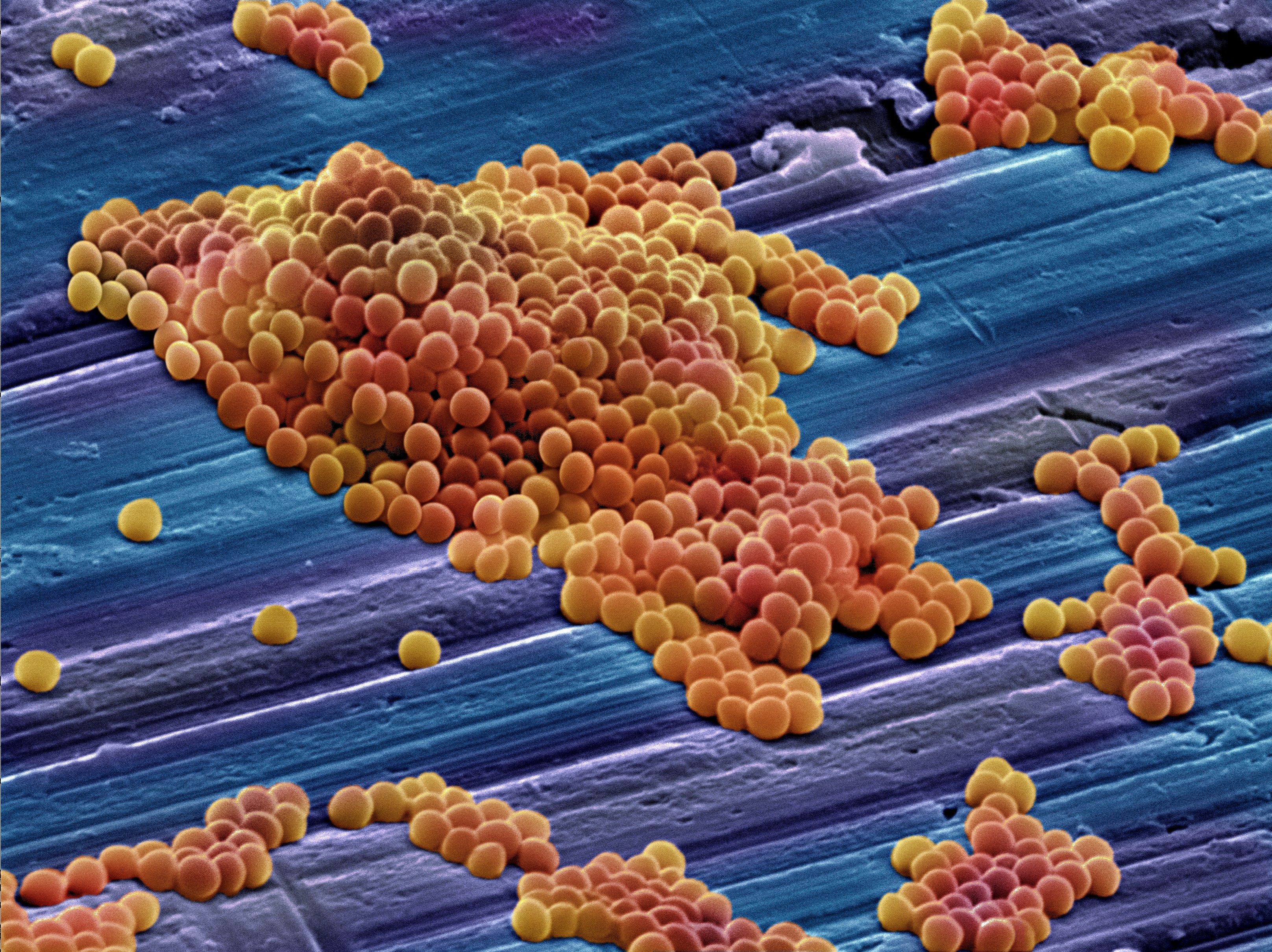

Antimicrobial resistance is a natural phenomenon where microbes develop immunity to medications, making certain infections difficult or impossible to treat.

This process is significantly accelerated by the increasing use of antimicrobials in humans, animals and the environment which, while killing off susceptible bugs, helps resistant bugs to proliferate more easily.

While antibiotic prescribing in the community has decreased for the first time since national surveillance commenced, antibiotics are apparently still being overprescribed.

Unnecessary antibiotic repeats may be a key contributor to this issue.

Repeat prescriptions filled within 10 days generally represent an appropriate continuation of the original antibiotic treatment. But those filled after this time-period are more likely to be associated with inappropriate use.

Health & Medicine

How do we close the gaps in appropriate antibiotic use?

Part of the problem is that some prescribing software packages used by GPs generally include repeats for antibiotic prescriptions by default. Simply removing default repeats could help to curb misuse.

Yet, default repeats represent only one potential target for better antimicrobial stewardship in the community.

Antibiotics continue to be prescribed for typically viral conditions like sinus, ear and upper respiratory tract infections, for which they are generally not recommended in the national guidelines.

For example, over 50 per cent of patients with influenza and 90 per cent of patients with acute bronchitis receive antibiotics when antibiotics aren’t recommended for these conditions.

Aged care homes, where infections are thought to be common and prescription numbers are high, appear to have high rates of sub-optimal prescribing. A large number of prescriptions don’t include ‘review’ and ‘stop’ dates, potentially leading to prolonged and unnecessary treatment.

It’s neither possible, nor desirable, to eliminate all prescribing outside the guidelines.

Indeed, in some instances, giving antibiotics against guideline recommendations may be justified, as may be the case for complex patients with weakened immune systems.

But these cases are a minority, and don’t explain the observed high level of prescribing that goes against recommendations.

Health & Medicine

The chemical warfare against bacterial superbugs

As the gatekeepers of community medical care, GPs can contribute substantially to reversing this trend.

Numerous factors push GPs to prescribe antimicrobial drugs, including time pressure, poor communication with patients and uncertain diagnoses.

GPs’ attitudes and beliefs about antibiotic resistance are also a factor. Australian surveys echo the findings of international studies, which indicate that while most GPs accept the seriousness of resistant infections and know of strategies to reduce them, they tend to perceive other health professionals and healthcare settings as having greater responsibility for this problem.

Public misconceptions surrounding antibiotics and antibiotic resistance play a similar role.

International public surveys have found that while most respondents understand that resistance is driven by excessive or unnecessary antibiotic use, they tend to underestimate their own risk from resistant infections, as well as their role in, and ability to minimise, the development of antibiotic resistance.

Studies of the Australian public have reported similar findings.

These attitudes may partly explain the pressure some patients place on GPs to prescribe antibiotics even when the cause is unlikely to warrant them.

Approximately 50 to 90 per cent of surveyed Australian parents believe antibiotics help treat coughs, sore throats and ear infections, which are nearly always viral.

Even when antibiotics are prescribed for the right conditions, patients don’t always understand or follow GPs’ instructions on how and when to take them, and may fill repeat prescriptions unnecessarily.

Raising public awareness and improving understanding of drug-resistant infections is crucial to fighting this problem, and remains a core objective of Australia’s National Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy.

Health & Medicine

The rise of the latest drug resistant superbug

Significant efforts toward this goal have already been made, with a particular focus on awareness-raising among (and the training of) healthcare professionals.

We have also had some education of the public through media reporting and educational campaigns.

But, as public misconceptions persist, more targeted, specific education and awareness initiatives will need to be implemented at scale.

These campaigns must be aligned with programs that encourage proactive GP engagement, and equip or incentivise prescribers to engage in shared decision-making with their patients.

Patients want doctors to help them understand the benefits and harms of antibiotics, how they work and why they are prescribed or withheld, yet too often fail to receive adequate explanations.

Quality improvement programs cannot be sustained without support from the government, professional colleges and providers, as well as some systemic interventions.

To avoid leftover doses of medication, antibiotic repeats could be restricted by better aligning the amount of antibiotics dispensed with the recommended duration of therapy.

A move to reduce the validity period of antibiotic prescriptions – currently 12 months – was considered by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee in 2015, and would also help limit inappropriate use.

Health & Medicine

Protecting patients and their doctors

While prescribers are generally opposed to restrictive interventions, they are likely to welcome easy fixes to technical issues like default repeats.

We need to work more pragmatically if we want to turn the tide on antimicrobial resistance.

NCAS deputy director and infectious diseases physician, Associate Professor Kirsty Buising, acknowledges that managing infections is difficult and an ongoing challenge.

“As physicians and researchers, we need to find ways to support each other as we strive to improve together,” she says.

“We don’t know all the right answers yet, but we are working to find out what helps.”

Banner: HeungSoon/Pixabay