Superhuman abilities could lurk under your skin

Insertable technology could launch a new type of human

Published 15 February 2016

Kayla Heffernan, PhD candidate, Department of Computing & Information Systems, University of Melbourne

A warning: the new approach to human evolution could make your skin crawl.

Frank* arrives home at the end of a busy Monday. Instead of fumbling for keys, he unlocks the front door with a wave of his hand. Frank is not a wizard, nor a powerful Jedi. He is a biohacker, a pioneer of insertable technology.

The technology that makes Frank’s special power possible is more convenient than a smartphone and less irritating than wearables such as fitness trackers. The key to his abilities (pun intended) are tiny devices that people voluntarily insert underneath their skin.

Frank’s insertable technology of choice is a grain-sized microchip encased in glass, inserted into the webbing of his hand. It contains a near-field communication (NFC) chip, technology that is very similar to Myki or PayWave.

Before the modification artist injected the tiny chip under his skin, Frank installed a panel on his front door that could “read” NFC data. He programmed the door panel to unlock when it received the right identification number, stored on Frank’s chip. Frank’s house remains secure, but his peace of mind no longer hinges on cumbersome, forgettable key chains.

“Even the operation of using my door becomes automatic, I walk up to the door and hold my hand up, it unlocks and I grab the knob and go,” says Frank.

No, the government cannot track your microchip

Popular media paint a cynical portrait of insertable technology. In Matthew Vaughn’s 2014 film Kingsman, criminal mastermind Valentine (Samuel L. Jackson) bullies humans into inserting chips in their necks. The device would save users from a bloody battle engineered by Valentine, yet has the unfortunate side effect of exploding if the user leaks Valentine’s malicious plan. Despite Hollywood’s vivid imagination, insertable technology is much less potent in real life.

For example, microchips might be the best method we have of finding lost pets. But microchips are not very good at finding you. If you lose your cat you must wait until it is found, taken to the vet and scanned. The microchips are programmed with identification data, but it does not contain GPS.

This technology is simply too bulky to place inside a person and even anti-chip organisations admit insertable GPS devices are not yet possible. If they are ever feasible, it would happen many years in the future.

Insertable technologies are not tracking devices, nor are they likely to trigger Armageddon anytime soon. They are also not the type of medical device doctors use to keep patients alive.

My research distinguishes between insertable technology and implants for an important reason. While patients receive implants out of medical necessity, personal choice is the reason people place insertable technologies into their body. People receive pacemakers because they have a heart or hearing problem, but Frank inserted his NFC device because he was curious about the technology.

They are developing advanced abilities, seeking improved convenience and gratifying their curiosity.

Insertable technologies are perhaps more similar to body piercings or tattoos than medical implants, because they are voluntary type of body modification.

Superpowers under your skin

Around the world biohackers and grinders are unsatisfied with the purely biological body. They are hearing colour, developing seismic sense and inventing sound systems that play directly inside their heads. Uniting the digital with the biological is the best way to find out if we can see warmth or take photos with the blink of an eye. As one my study participants Michelle* said:

We should be able to enhance senses that we have naturally instead of just improving them when they’re not working as well as they should.

Some of the more daring biohackers are discovering extra senses by inserting magnets into their bodies. Campbell’s* insertable magnet vibrates when it encounters an electromagnetic field, alerting him to nearby objects. This is more than a cool party trick – Campbell can walk around a room with his eyes closed, a feat that offers unparalleled opportunities for people with low vision.

‘Cyborg’ Moon Ribas has taken insertable magnets a step further, using the technology to connect her body with Mother Nature. From California to China, her body acts as a biological tremor detector that senses when earthquakes happen around the world.

Concerns and ethics

Insertable technology research and biohacker curiosity opens a range of concerns and asks many difficult questions. If you had an elderly parent with Alzheimer’s disease, would you place a bracelet on their hand to prevent them wandering and getting lost? Is there a difference between placing this device on their wrist or under their skin? What if your parent wants to tear the device out?

While we may not have the answers today, we need to start considering these possible scenarios.

We cannot yet say whether consequences will be good, bad or mixed. But we must acknowledge the potential of insertable technology to disrupt life as we know it.

If you have an insertable device and would like to take part in this research, contact Kayla Heffernan.

*names changed

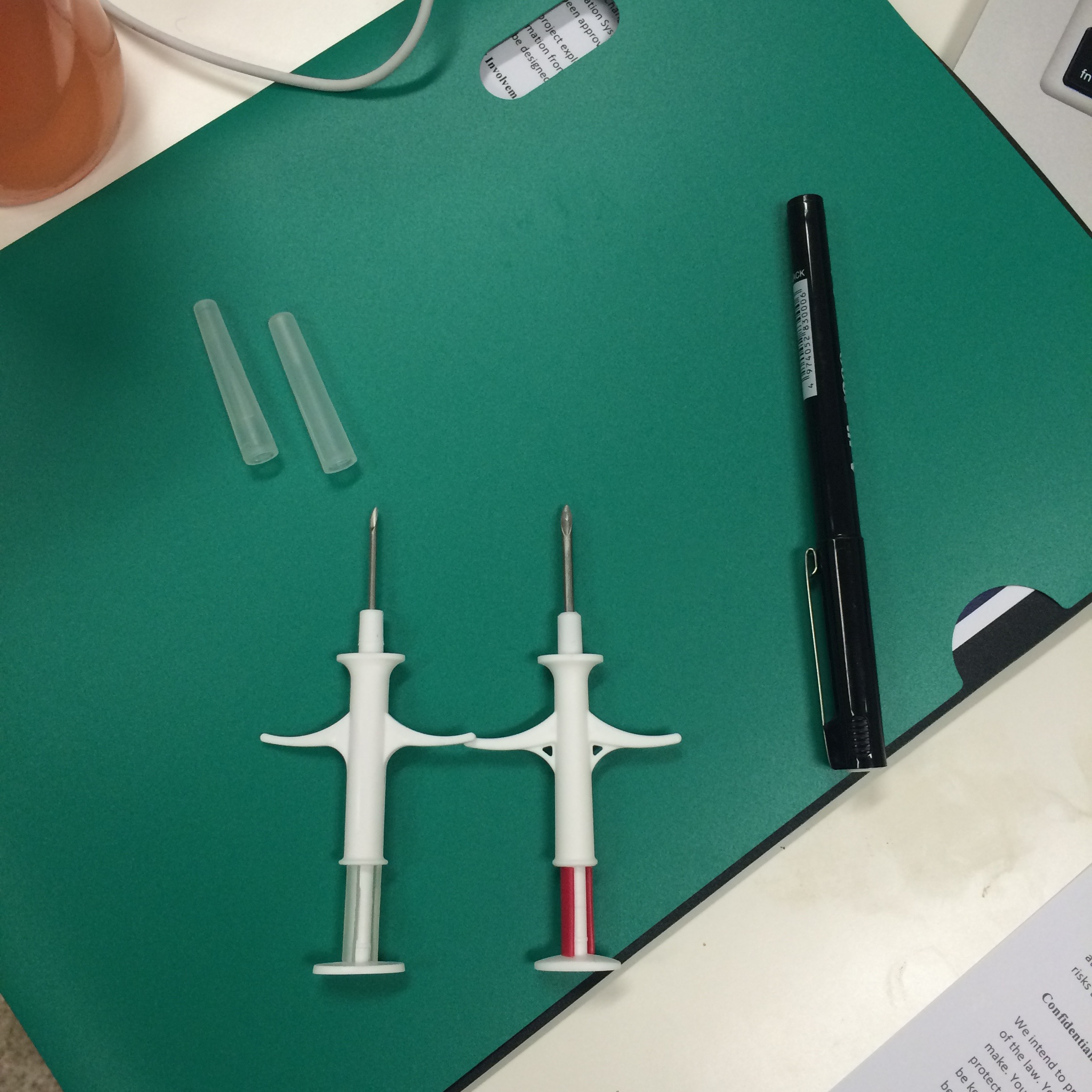

Banner image: Two near-field communication chips. The smallest is no larger than a grain of rice. Picture: Kayla Heffernan