Health & Medicine

The birth of syphilis surveillance in Melbourne

In a world where sex and sexuality are more public than ever, how can we overcome the persistent stigma attached to sexually transmissible infections?

Published 2 June 2019

Most people would agree that pleasure is an important part of a sexual relationship. But when it comes to sexually transmissible infections (STIs), this pleasure has long been associated with self-indulgence, lack of self-control and deviance.

This is because for centuries STIs were seen as acquired through illicit or marginalised behaviour.

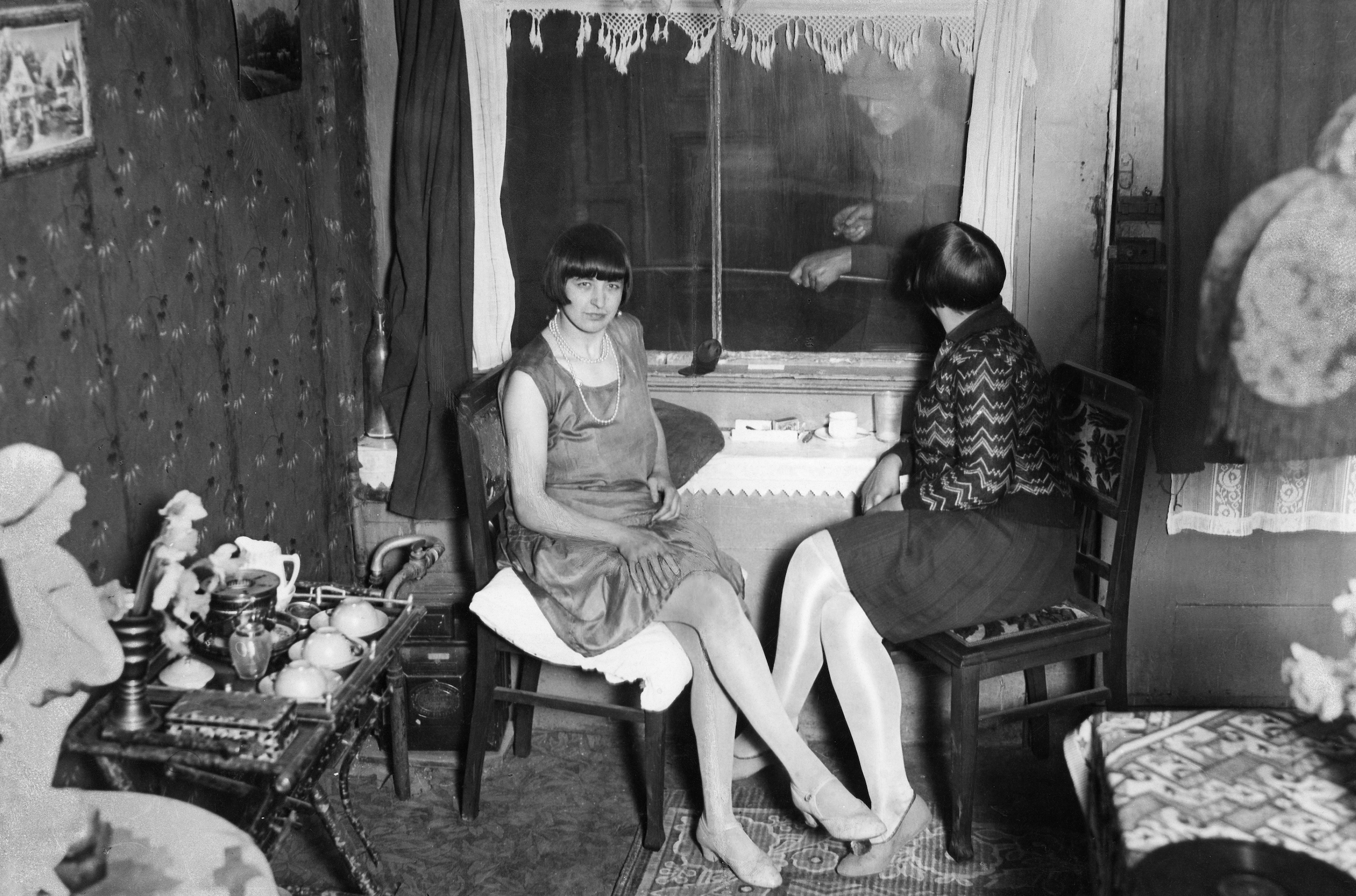

When it came to trying to keep STIs under control, this idea was a powerful influence both on medical approaches to treating infection, and on public health policy. So euphemisms were used to describe STIs, their treatment was kept hidden and legislation focused on the control of prostitutes who were seen as a key cause of infection.

But STI transmission was poorly understood then, and STI testing and treatment was in its infancy.

Fast forward 100 years.

Health & Medicine

The birth of syphilis surveillance in Melbourne

Norms around sex and sexual behaviour have changed. Today, same-sex relationships, gender diversity, explicit sex on TV, sex work, sexting, pornography, sexually explicit advertising and sex toy stores are all widely accepted. It’s a different world.

So why do we still have so many hang ups when it comes to talking about sexually transmitted diseases?

Both in Australia and around the world, we currently have rising rates of STIs. In the recent past, it was men who had sex with men who were seen as the peak group for STI transmission in the same way female sex workers or ‘good time girls’ were blamed in earlier generations; even though people of all ages and sexual preferences contributed to our pool of infection.

Today, we understand that an STI can be transmitted just as easily by someone who has only had sex once, as it can by someone with scores of partners.

And the high-risk age group for STIs is widening.

While different STIs show slightly different patterns of disease, for most of the last century, the highest rates for STIs were among people aged 18 to 25. There are no surprises there, as this is the time when young people are exploring their sexuality. But today the highest rates now extend to the wider 16 to 29 age group. This suggests a shift in behaviour of some kind.

Perhaps people simply don’t perceive STIs as the serious threat they once did?

It is true that antibiotics, antivirals and vaccines have vastly improved the treatment landscape for infections like HIV, syphilis, gonorrhoea, chlamydia, herpes and the human papillomavirus (HPV).

Health & Medicine

We need to talk about chlamydia

But it is also likely that people don’t fully understand their risk of acquiring an STI and have difficulty in estimating it.

We know from studies of high school students that they are more knowledgeable than previous generations about the biology of sex, but still want more information about negotiating relationships.

It’s possible that in the current time when dating apps make it easier to ‘hookup’ up than ever before, people are paradoxically even less relaxed when it comes to conversations about sexual safety.

Certainly, one thing that hasn’t changed over time is people’s reluctance to discuss their sexual behaviour with a health professional.

Most STI diagnoses in Australia are made in general practice, but unless a patient requests sexual-health testing or advice, or comes in with a complaint which is obviously linked to a sexual health issue, our research with young men and older people shows it’s unlikely a GP will even raise the topic of sex.

From a workflow perspective, this is entirely reasonable – in an average consultation GPs can’t be expected to inquire about every possible aspect of their patients’ lives. And often they will consider other aspects of their patient’s health as a higher priority than their sexual health.

However, in this 16 to 29 age group, there is a vast sea of undiagnosed chlamydia, as well as rapidly rising rates of gonorrhoea and syphilis infection. If left untreated, these diseases can have a devastating impact on an individual’s future fertility.

It’s a missed opportunity if the patient doesn’t ask about testing or the GP doesn’t offer it.

Health & Medicine

Lifting the lid on HIV

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

A century ago people’s reluctance to even talk about sex meant that STIs were referred to as ‘Social Diseases’ or ‘the Social Evil’, until soaring rates of infection precipitated some plain speaking, and the words ‘venereal disease’ finally began to be used.

This change was testimony to the many health professionals and members of the Australian Association for Fighting Venereal Diseases who lobbied hard to introduce public sex education.

So, there have always been people who spoke out for the need to de-stigmatise these diseases, to just treat them as diseases, without making any judgements about how they were acquired.

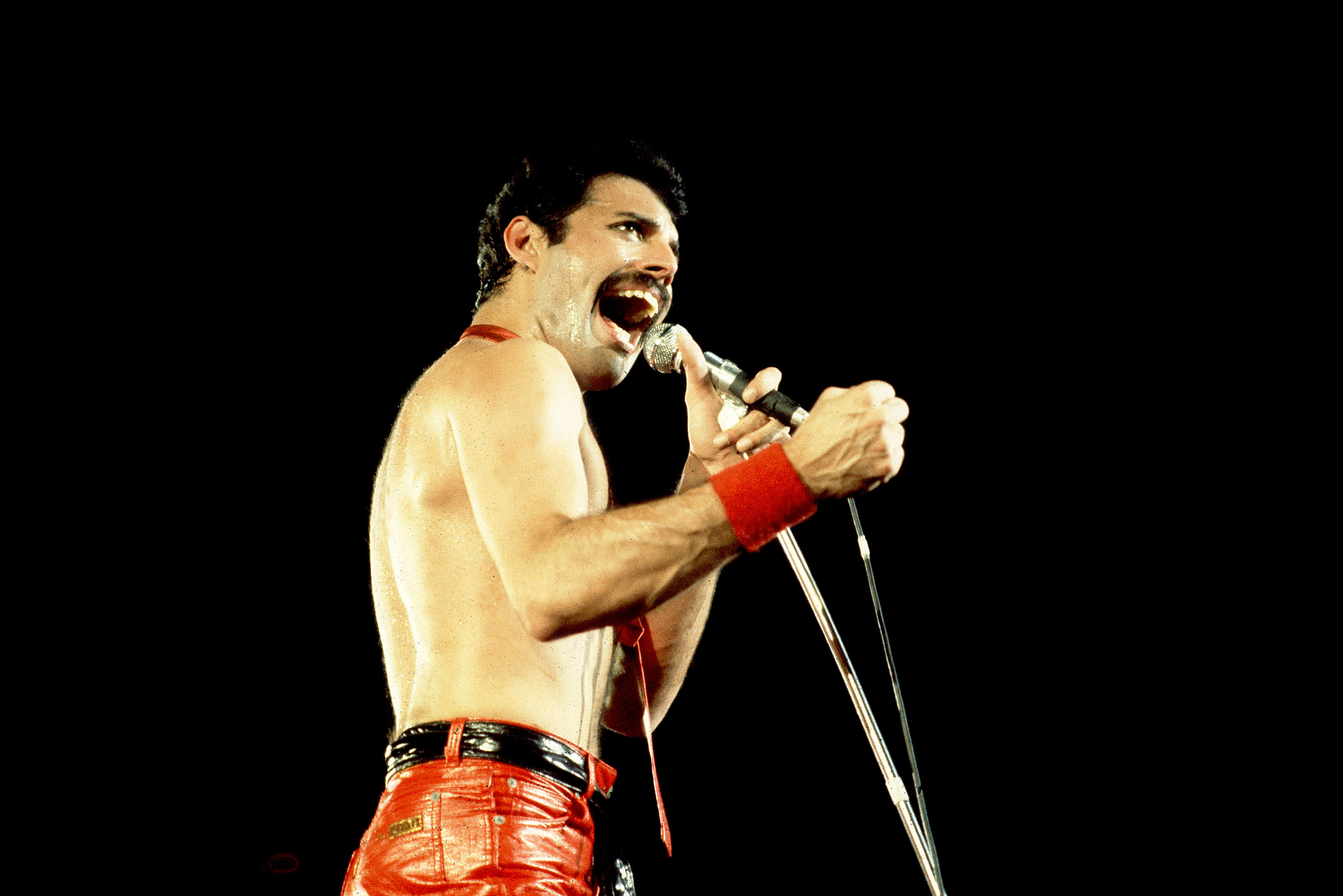

In the last 30 years, much work has been done to de-stigmatise HIV/AIDS, including advocacy by public figures like Queen frontman Freddie Mercury, tennis great Arthur Ashe and basket baller Magic Johnson.

And people who aren’t so famous are also making a difference. Take Steve Spencer, the Sydney man recently diagnosed with HIV despite having regularly taken pre-exposure prophylaxis (PreP) to prevent him acquiring the infection.

But who are the poster girls or boys for syphilis, gonorrhoea, chlamydia or herpes? Why have they no public advocate? Is it possible that when it comes to the term ‘sexually transmissible infections’ there is still too much stigma attached?

It is easy to underestimate the power of a label or a word.

The old label of ‘manic-depressive’ sounded way more uncontrollable than the ‘bi-polar disorder’ we talk about today. When it comes to ‘sexually transmissible infection’, the words ‘transmissible’ and ‘infection’ are fine on their own or even together, – but add ‘sex’ and we can be taken on a whole other journey.

HERE’S A THOUGHT

Maybe it’s time we just took the ‘sex’ out of sexually transmissible infections? Could they simply join the other transmissible diseases of which we are all aware?

Health & Medicine

Why is no-one talking about safe sex for the over 60s?

You could then just tell a potential sexual partner: “Sorry, not tonight. I think I might have something, and don’t want to risk passing it on till I’ve seen the doctor.”

For all they might know, you could be worried about the flu or gastro or chlamydia, and you are simply being responsible.

What’s more, this could even offer a segue into the topic of safe sex – a conversation always best had before the sex occurs.

And when going in to see your GP, all you need to say is: “I want to make sure I don’t have any transmissible diseases before I go into my next relationship.”

What could be easier than that?

This work was conducted during Professor Meredith Temple-Smith’s residency at Fondation Brocher in Switzerland.

Banner: Getty Images